The Sinking of the Bismarck (13 page)

Read The Sinking of the Bismarck Online

Authors: William L. Shirer

After 3:00

A.M.

the British destroyers appeared to have given up their futile attack. A lull set in—the lull before the storm. Both sides were waiting for the dawn—the British joyfully, the Germans with despair. Aboard the crippled

Bismarck

there were few illusions about what daylight would bring.

The destroyers reappeared toward 6:00

A.M.

, in the closing moments of darkness, and the German battleship opened fire on the nearest one. This was the

Maori

, which approached to within 9,000 yards and fired her last two torpedoes. She then ducked away from the

Bismarck

’s 15-inch shells. There were no hits by either side.

At 6:25 on the morning of May 27, Admiral Luetjens radioed Naval Group West that the

situation remained unchanged. At 7:10, in the first dim rays of daylight, he dispatched another signal: “Send U-boat to save War Diary [log].”

It was the last message he ever sent.

Chapter Eleven

Final Battle: The Sinking of the

Bismarck

To the men on the battleships

King George V

and the

Rodney

, waiting impatiently for the kill, it seemed, as one officer later wrote, that the dawn would never come.

The crews were at their battle stations all through the long night, though half of them at a time were given permission to snatch some sleep at their posts. The captains of the two ships remained at their compass platforms. They kept track of the plotting of their own positions and that of the enemy, as reported during the night by the destroyers which were snapping at the heels of the

Bismarck

.

They also kept scanning the eastern sky for

the first faint hint of dawn. When Commander W. J. C. Robertson, chief of staff for operations, thought he saw it, he went down to his cabin on the

King George V

to fetch his steel helmet. He was amused to see four large rats scurrying about in terror. Apparently even the rats aboard knew the ship was going into battle.

The Commander in Chief also had been up most of the night, taking in the signals from the destroyers and waiting as impatiently as everyone else for the daylight to break. Admiral Tovey still didn’t know exactly where his prey was. For nearly a week the thick clouds had hidden the sun by day and the stars by night. The ships could not get a bearing. They had to plot their position as well as that of the

Bismarck

by dead reckoning. This was never completely accurate.

For this reason the Commander in Chief during the night had asked Captain Vian’s destroyers to fire star shells to indicate the

Bismarck

’s location. But in the rain and low clouds he had not been able to see them over the horizon.

It soon became obvious that daylight was not going to bring any improvement in the weather.

As the skies began gradually to lighten on May 27, the clouds still hung close to the sea. The rain did not let up. The seas remained high. The wind blew out of the northwest as strong as ever. In the wretched visibility Sir John began to search for the

Bismarck

. Because of the fuel shortage of both his battleships, he knew he had to find the German leviathan and sink her within two or three hours at the most. By 10:00

A.M.

they would have just enough oil to limp home.

At this critical juncture the cruiser

Norfolk

came to his aid, as she had at the beginning of the chase off Iceland. Though herself dangerously low on oil, she had been racing south all night to get in on the fight. At 8:15

A.M.

her lookouts sighted the

Bismarck

eight miles dead ahead. Captain Phillips turned his cruiser hard over to get quickly out of range of the big ship’s guns. As he swerved he sighted the

Rodney

and

King George V

in the distance. He could thus serve as a visual link between them and the enemy.

Admiral Tovey’s two ships were actually off course. Had it not been for the

Norfolk

the

Commander in Chief might have missed the

Bismarck

once again. Quickly he altered course. Twenty-eight minutes later he finally sighted his target twelve miles directly ahead. It was the first time he had actually seen the

Bismarck

. After nearly a week of frustrating, nerve-wracking pursuit, he had cornered her at last.

He moved in at once for the kill. He could see that the

Bismarck

was moving very slowly, headed into the wind. But he had no reason to doubt that Admiral Luetjens could still use his excellent guns with customary accuracy. The German battleship had managed to dispose of the

Hood

in a few minutes.

Admiral Tovey signaled to the

Rodney

, which was about a mile off to his port side. He told her she was free to move and to fire as she thought best but should conform generally to the flagship’s maneuvers. He was not going to fight the rigid battle that had cost the fleet the

Hood

.

At precisely 8:47

A.M.

on May 27 the

Rodney

opened fire with her 16-inch guns. Within the minute the

King George V

got off her first salvo of 14-inch shells. The

Bismarck

did not reply for

about two minutes. But when she did, her fire was accurate. Her third salvo straddled the

Rodney

, on which she concentrated her big guns, and almost scored a direct hit.

Captain Dalrymple-Hamilton on the

Rodney

turned a little to port so he could bring all his guns into action. Soon he was pounding the

Bismarck

with full broadsides. The

King George V

plowed straight ahead. In this position she was unable to use her aft guns. But she was rapidly closing the range. The cruiser

Norfolk

, which had refrained from firing at the

Bismarck

during the earlier action with the

Hood

and the

Prince of Wales

, now joined in the battle. She began firing with her 8-inch guns at 20,000 yards.

A second British cruiser soon entered the fray. This was the

Dorsetshire

. She had been escorting a convoy 600 miles west of Cape Finisterre on the morning of May 26 when she picked up the signal that the

Bismarck

had been found again. Captain B. C. S. Martin saw that the enemy was a mere 300 miles almost due north of him. On his own he left the convoy and steamed off at twenty-eight knots to try to get in on some action.

He had arrived on the scene just in time. At 9:04

A.M.

the

Dorsetshire

turned her 8-inch guns on the enemy and opened fire.

Thus by shortly after nine o’clock the

Bismarck

, helpless to take avoiding action because of the damage to her rudders, was being shelled by two British battleships and two heavy cruisers. Such superiority soon began to tell. The British warships were now scoring direct hits with their big shells. One of the first salvos was seen to knock away part of the

Bismarck

’s bridge. The German guns, though still blazing away, were losing accuracy.

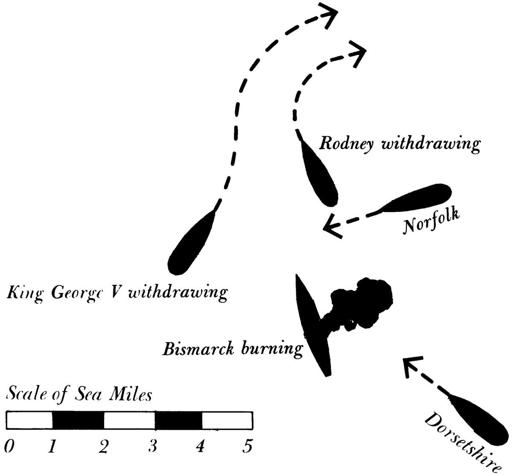

At one minute before nine o’clock, Sir John turned his flagship south so he could bring a full broadside against the enemy. The

Rodney

followed her. They were both now only 15,000 yards from the German ship, which was yawing roughly north. After fifteen minutes of continuous exchange of salvos Admiral Tovey found that he had passed the

Bismarck

. He turned his ships around for another run parallel to the enemy, this time northward.

The range had lowered to a bare 8,000 yards.

Both the

Rodney

and

King George V

were delivering full broadsides as fast as their big guns could be reloaded. The

Bismarck

was obviously hurt from such a murderous fire at such close range. A large fire was seen belching smoke and flame amidships. Some of her 15-inch guns were no longer firing. A lookout on the

Norfolk

saw two of them drop almost to the water line. Others pointed crazily at the sky. Their hydraulic controls, it was evident, were no longer functioning. One gun turret was blown clear away, its twisted metal toppling against the bridge.

About ten o’clock, a little more than an hour after the action had started, the last of the

Bismarck

’s guns were silenced. She had been reduced to a flaming, smoking, battered hulk. Through the jagged shell holes in her side could be seen the bright flames of fires consuming her insides.

And yet above the blazing inferno the

Bismarck

’s flag still flew. She was beaten. She was finished. But she would not surrender.

***

It is almost impossible to reconstruct the holocaust

as it was experienced at this hour by the 2,400 Germans aboard the battered battleship. Each of the 118 survivors later had a tale of horror to tell. But only three of them were officers, all of junior rank. The overall picture as seen from the bridge can never be told. Admiral Luetjens did not send out a single message about this last battle. He did not even signal, as was customary, that it had begun.

He could not, in any case, have sent many messages. One of the first salvos from the British battleships blew away the admiral’s bridge and with it Admiral Guenther Luetjens. Captain Lindemann might have survived. Miraculously he escaped injury even when

his

bridge was demolished by a British shell. Junior officers urged him to jump overboard with them when it became clear that the ship was doomed. But he stuck to his post to the end.

Battered and silent and afire though she was, the

Bismarck

would neither surrender nor sink!

Admiral Tovey thought his guns had poured enough heavy shells into her to sink a dozen battleships. During the run to the south the

Rodney

had fired six torpedoes at the

Bismarck

and the

Norfolk

had fired four in an effort to dispatch her by this means. All had missed. But the bombardment by both heavy and light guns had not let up for a moment. And still the flaming enemy hulk kept afloat.

The Commander in Chief was both puzzled and impatient. He had never imagined that a ship could take so much punishment and not go down. Time was getting short. German long-range bombers from France had been reported approaching. German U-boats were known to be converging on the scene. The

Rodney

and

King George V

were already zigzagging as they fired. This was a necessary precaution against hostile submarines. Worst of all, the oil tanks on the two British battleships were so low by ten o’clock that Tovey was not sure he would have enough fuel to get them home.

Impatiently the Admiral sent orders to Captain Patterson on the bridge of the

King George V

.

“Get closer! Get in there closer! I can’t see enough hits!”

The two battleships plowed in closer, the

Rodney

turning so she could fire with all her nine 16-inch guns. She also dispatched her last two torpedoes at a range of only 3,000 yards. One of them hit—the first occasion in naval history that a battleship had ever torpedoed another. The

Norfolk

also launched her last four torpedoes at 4,000 yards. One of them hit, but still the

Bismarck

did not go down.

Vice-Admiral Somerville asked for another try at it with his Swordfish from the

Ark Royal

. They had disabled the

Bismarck

in the first place. Perhaps they could finish the job!

The planes took off from the carrier at 9:25

A.M.

, but as soon as they arrived over the German battleship they saw that it would be impossible to get down to launch their torpedoes. The shell fire from their own ships was too intense. The squadron leader signaled Admiral Tovey asking that he cease fire while the planes made their run to the target.

There was no reply—except from the

King George V

’s anti-aircraft guns, which started to fire at the Swordfish in the belief they were German planes. Captain Patterson noticed the mistake at

once and told the officer commanding the flak guns to desist.

“Can’t you see our airmen waving at you?” he asked.

“I thought they were Huns shaking their fists at us,” the officer replied.

It was now 10:15

A.M.

, and Admiral Tovey had to make a hard decision. It was absolutely imperative for him to turn his big ships home. On their dwindling oil reserves, they could make only a slow speed as it was. This would add to their peril if the German bombers and submarines attacked.

He looked over a last time at the burning wreck of the ship he had been firing at with all the guns and torpedo tubes of the fleet. She still floated. But he knew she was finished. She would never make port. Satisfied that he had destroyed her but disappointed at not having sunk her, he ordered the

Rodney

to form behind him as he set course northeast for Britain.

As he steered for home he sent back one last signal. If any of the cruisers or destroyers had any more torpedoes they might launch them

point-blank in a final effort to send the battered

Bismarck

to the bottom.