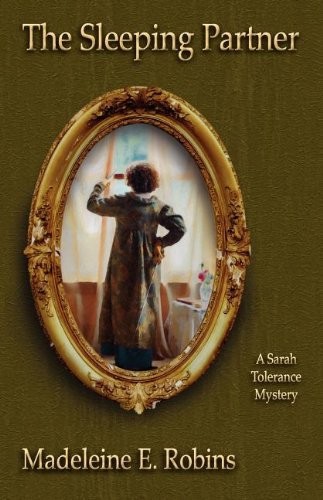

The Sleeping Partner

Read The Sleeping Partner Online

Authors: Madeleine E. Robins

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #Women Sleuths, #Mystery & Crime

The Sleeping Partner

A Sarah Tolerance Mystery

Madeleine E. Robins

Plus One Press

San Francisco

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations and events portrayed in this novel are either the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Plus One Press

THE SLEEPING PARTNER. Copyright © 2011 by Madeleine E. Robins. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. For information, address Plus One Press, 2885 Golden Gate Avenue, San Francisco, California, 94118.

Book Design by Plus One Press

Cover portrait photo © 2011 by Annaliese Moyer, used under license from Stage Right Photo: www.stagerightphoto.com.

EB362x5501

First eBook Edition: December, 2012

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Penny and Emil, with love and history

The Sleeping Partner

Another London, April 1811

Chapter One

No one who had seen Miss Sarah Brereton as a child would have taken her for a heroine. She was a well-behaved girl, affectionate and active, given to rolling hoops and running races with the gardener’s children. Her upbringing was neither intellectual nor revolutionary, being designed to make her what she was destined to be: the well-bred wife of a gentleman of means. That she had failed to achieve this goal was not the fault of her family but derived from some flaw in her character: at sixteen, Miss Brereton had fallen in love with her brother’s fencing master and eloped, ruining forever her chances at respectability and marriage. Seeking to contain the damage, Sir William Brereton disowned his daughter and forbade to have her name mentioned. With the girl as good as dead, the honor of the Breretons was restored to a near-unsullied state. The family went on much as before.

In this, Sir William was particularly prudent. Society is harsh to those contaminated by the breath of female indiscretion. Should he have suffered his neighbors to whisper after him in ballrooms, or permitted his daughter’s misjudgment to spoil her brother’s chance at an advantageous marriage? Sir William saw no reason to waste further resources upon a child who had so lightly and ungratefully disposed of her virtue. He washed his hands of the girl; his heir did the same.

For society exists to suffer revelry in men, reward virtue in women, and to promote and protect the sanctity of marriage as the best instrument to secure property. Even in the Royal family these distinctions are observed. The Princes carouse as they please; only the Prince of Wales married young, and that marriage, to a Catholic widow, drove his Royal father to the madhouse and removed the prince from succession. There was no doubt that marriage and family had tamed the Prince’s most exuberant impulses; one had only to look at the excesses of his brothers. And the Queen Regent took care to arrange marriages for her six daughters as early as she might, in the belief that an unmarried woman, even a Royal one, was always in danger of corruption.

By such examples is a nation led. Women learn early that unblemished virtue is the brightest jewel in their adornments. Young men learn that any girl with a question about her may be ripe for the plucking. And families know the dire consequences which any breach of feminine virtue may bring to them. Once her reputation is lost, a woman might as well adopt a

nom d’amour

and resign herself to a life of whoredom. Reputation, more than virtue itself, must be protected.

This laudable goal is sometimes achieved with pistol or sword in a private meeting at dawn. Sometimes it is achieved through the power of a bit of information brought to light, or a secret well hidden. Miss Sarah Tolerance, who had begun her life as Sarah Brereton, was of the opinion that a woman who makes her living by the acquisition and protection of information had best keep her pistols primed and her sword edged and ready.

Miss Tolerance had been set down by a hackney coach in Fleet Street at Whitefriars, not far from Bridewell Prison. Even at six in the morning the streets around the prison were thronged, both with victualers who were fetching in provisions, and with the hangers-on of prisoners. The street was clamorous: vendors and visitors yelled to each other; the prisoners screamed out at the windows. The stench of too many persons packed tight together—few of them given to bathing—vied with odors from the prison sewer. In the crowd whores and pickpockets moved freely; every brief stir or outcry meant busy fingers at work.

Miss Tolerance followed Whitefriars toward Salisbury Square, happy that she had no business at the prison today. The morning fog was burning off, leaving thin, coal-hazed sunlight and a damp breeze in its wake. She turned left and through the arched entrance to Hanging Sword Alley, where many of London’s

salles des armes

were to be found. Half-way down the street she entered a building much papered over with bills advertising cures for pox and fever, and climbed to the second floor. She had barely raised her hand to knock when the door was opened by a scrawny, spry man quite old enough to be Miss Tolerance’s grandfather. His face was narrow, his eyes small and bright blue, and his lopsided jaw gave him a comical look. His white hair was worn in an old-fashioned queue bound with black ribbon. He wore breeches, shirt, and waistcoat, and was stocking-footed. He looked in turn and without surprise at Miss Tolerance’s unusual attire: men’s breeches, boots, and coat, and a sword hanging at her left hip.

“Come ready, have you?” The old man grinned. “Come in, then, Miss T., and let’s to work.”

“Thank you, Mr. Blaine.” Miss Tolerance shed her coat and removed her boots.

Mr. Richard Blaine’s fencing

salle

was not the most celebrated in London; Mr. Blaine himself was not an extraordinary fencer. He was, however, an excellent teacher and, quite as much to the point, he was willing to have Miss Tolerance bout with him when she had the time. That she paid for her lessons was, he assured her, beside the point. It was a pleasure to him to fence with a pretty girl, particularly one who could teach him a trick or two.

“If that is so, perhaps you ought to be paying me?” Miss Tolerance stretched and lunged, feeling her chilled muscles begin to warm.

“Ah, but there’s the rent on this magnificent space,” Mr. Blaine said quickly.

“And the upkeep of the magnificent Mrs. Blaine and your grandchildren,” Miss Tolerance agreed. “I don’t begrudge the shilling, Mr. Blaine. Now, sir, are you ready?”

The two fencers saluted each other briskly and went to it. Mr. Blaine was, by his nature, a quick and dramatic fencer given to sudden inspiration. After a flurry of attacks in the high line, he lunged for Miss Tolerance’s left hip; Miss Tolerance parried in

sept

with enough force to knock Mr. Blaine’s sword from his hand, and had her point at his throat before he could move. Blaine laughed; Miss Tolerance dropped her point and permitted him to retrieve his blade.

“A neat touch, Miss T!”

They returned to work.

Within a quarter hour Miss Tolerance’s shirt clung damply to her back and her face was flushed with exertion. Mr. Blaine had ceased his regular stream of quips and comments and saved his breath for his work. Both fencers were grinning with the pleasure of hard work well done, and so involved that neither one heeded the first, or even the second knock on the door. At the third, Miss Tolerance dropped her point and stepped back. “Someone is here, sir.”

Blaine dropped his own point and looked to the door.

“Sit and rest you, Miss T. I’ll return in just a moment.” Mr. Blaine put down his foil, wiped his face and hands with a spotted kerchief, and went to the door. Miss Tolerance dropped onto a bench and wiped her own face and hands, paying no attention to Mr. Blaine’s conversation until the visitor in the doorway shoved the old man into the room and advanced upon him threateningly.

“You’ll give me what I come for, you mick sharper! You and them false tats! You ain’t comin’ over me—” The man was square-jawed, square-built, and grubby. His color was high, and in his maroon coat he resembled a bad-tempered brick.

Mr. Blaine held out a placating hand. “Mr. Wigg, I tell you true, I keep no money here. I could not return your money even were I of a mind to do so. And as the dice I used were honest as the dawn—” Mr. Blaine spoke quietly, the only sign of distress a Killarney lilt to his speech that Miss Tolerance had never detected before.

“Is there a problem, sir?” Miss Tolerance rose to her feet and spoke clearly, as calm as her fencing partner.

If Mr. Wigg was startled to find a witness in the

salle

, he did not permit it to distract him from his quarry. “You took seventeen shillin’ off me,” he said to Blaine. “Ain’t no one could do that but they was cheatin’.”

Miss Tolerance stepped closer. “Is it the sum that troubles you, sir? I have known thousands of guineas to change hands at dicing, with quite honest dice. What makes you believe that Mr. Blaine’s dice were fixed?”

This time Mr. Wigg turned his head. “You’ll keep out of it,” he snarled.

Then he stopped, dumbstruck, taking in the sight of Miss Tolerance. Her dark hair was pulled back from her face and braided; her waistcoat covered the most obvious evidence of her gender. Still, it was clear to anyone with an eye to see it that Miss Tolerance was a female in the costume and occupation of a man. Mr. Wigg looked as appalled as a man who has found half a worm in his apple.

“You keepin’ a nuggery, now?” he snarled at Blaine.

“Merely a fencing school, Mr.—Wigg?” Miss Tolerance said “It is very nervy of you indeed, insulting a man with a sword—and his student. But I suppose you think we will not offer much resistance to your bullying.”

Mr. Blaine looked at Miss Tolerance warily, as if he was not certain her interference was wise. Miss Tolerance was not to be intimidated; she had taken Mr. Wigg in dislike. Mr. Wigg appeared to return the feeling.

“Have you evidence that Mr. Blaine’s dice were fixed?”

Wigg faltered, then turned back to Blaine. “Seventeen shillin’ you took off me, and I want it back.

Wiv

interest!”

“I haven’t got it, I told you,” Blaine said. “I would be happy to permit you to win the money back, or even to have you come at another time to discuss—”

“So you can ‘ave a bunch of bully-boys ready to crush me skull for me? The ‘ell with that. You’ll give me my money or I’ll take it out your skinny ‘ide.” Wigg stepped forward again, towering over Mr. Blaine.

“Do you prefer to handle this yourself, sir, or may I assist?” Miss Tolerance asked politely.

This appeared to be more than Mr. Wigg could stand. “You? ‘Elp? I’ll soon teach you to mind your place, you whore!”

“There have been a good number of gentlemen who have tried to do so, sir. Curiously, none has yet managed it.” Miss Tolerance took a relaxed stance in the center of the room, her sword point down.

“Don’t think that cheese-toaster’ll ‘elp you,” Wigg warned. “What you need’s the sense beat into you.” He glanced around him nonetheless and made for a rack of weapons near the window. He swung back to Miss Tolerance with a rapier in his hand. He had chosen badly, she noted; while none of Mr. Blaine’s swords were untended, this was an old blade, the grip too small for Wigg’s beefy hand. Mr. Blaine made a noise of professional dismay at the mismatch of man and blade.

“Forgive me, Mr. Blaine. Do I interrupt? Would you prefer that I step back?”