Read The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment And The Tuning Of The World Online

Authors: R. Murray Schafer

The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment And The Tuning Of The World (41 page)

Any sound intentionally uttered within an enclosure is more or less private, more or less connected with the cult—whether this be the cult of the lover’s bed, of the family, of religious celebration or of clandestine political plotting. Primitive man was fascinated by the special acoustic properties of the caves he inhabited. The caves of the Trois Frères and Tuc d’Audobert in Ariège contain drawings depicting masked men exorcising animals with primitive musical instruments. One imagines sacred rites being performed in these dark reverberant spaces in preparation for the hunt.

In the Neolithic cave of Hypogeum on Malta (r. 2400 B.C.), a room resembling a shrine or oracle chamber possesses remarkable acoustic properties. In one wall there is a largish cavity at eye level, shaped like a big Helmholtz resonator,

ae

with a resonance frequency of about 90 hertz. If a man speaks there slowly in a deep voice, the low-frequency components of his speech will be considerably amplified and a deep, ringing sound will fill not only the oracle chamber itself, but also the circumjacent rooms with an awe-inspiring sound. (A child or a woman will not be able to produce this effect, the fundamental pitch of their voices being too high to activate the resonator.)

Early sound engineers sought to carry over special acoustic properties like these into the ziggurats of Babylon and the cathedrals and crypts of Christendom. Echo and reverberation accordingly cany a strong religious symbolism. But echo and reverberation do not imply the same type of enclosure, for while reverberation implies an enormous single room, echo (in which reflection is distinguishable as a repetition or partial repetition of the original sound) suggests the bouncing of sound off innumerable distant surfaces. It is thus the condition of the many-chambered palace and of the labyrinth.

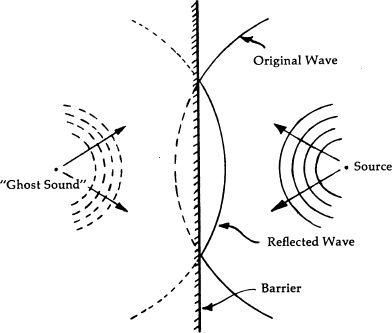

But echo suggests a still deeper mystery. Acousticians will explain that the reflection of a sound off a distant surface is simply a case of the original wave bouncing back, the angles of incidence and reflection being equal. In order to understand this effect one may project a mirror image of the original sound deep behind the surface, at exactly the same distance and angle from the surface as the original. In other words, every reflection implies a doubling of the sound by its own ghost, hidden on the other side of the reflecting surface. This is the world of alter-egos, following and pacing the real world an instant later, mocking its follies. Thus, a far more potent image than Narcissus reflected in the water is that of Narcissus’s alter-ego mocking his voice from unseen places behind the rocks. Lucretius, whose philosophy blends science and poetry so skillfully, catches something of this magic quality in his description of the echo:

One voice is dispersed suddenly into many voices. … I have even seen places to give back six or seven cries when you uttered one: so did hill to hill themselves buffet back the words and repeat the reverberation. Such places the neighbours imagine to be haunted by goat-foot satyrs and nymphs … they tell how the farmers’ men all over the countryside listen, while Pan shaking the pine leaves that cover his half-human head often runs over the open reeds with curved lip, that the panpipes may never slacken in their Hood of woodland music. … Therefore the whole place is filled with voices, the place all around hidden away from sight boils and stirs with sound.

Reverberation and echo give the illusion of permanence to sounds and also the impression of acoustic authority. Thus they convert the sequential tones of melody into the simultaneously heard chords of harmony. In open Greek amphitheaters where reverberation was of negligible significance ("never more than a few tenths of a second") harmony was also absent in the musical system. The fact that the theory of harmony was slow to develop in the West was probably due to the way in which Pope Gregory and the medieval theoreticians took over Greek musical theory. Here we have an example of a cultural inheritance inhibiting a natural development, that is, the polyphonic potential of the enclosed forms of Romanesque and Gothic cathedrals. The reverberation of the Gothic church (up to 6–8 seconds) also slowed down speech, turning it into monumental rhetoric. The introduction of loudspeakers into such churches, as has recently happened, does not prove the acoustic deficiency of the churches but rather that listening patience has been abbreviated.

The size and shape of interior space will always control the tempo of activities within it. Again this may be illustrated by reference to music. The modulation speed of Gothic or Renaissance church music is slow; that of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is much faster because it has been created for smaller rooms or broadcasting studios. This development reached its climax in the highly concentrated, information-packed music of the twelve-tone composers. The contemporary office building, which also consists of small, dry spaces, is similarly suited to the frenzy of modern business, and thus contrasts vividly with the slow tempo of the Mass or any ritual intended for cave or crypt. Now again, the attenuated effects of the newest music seem to suggest a contemporary desire to slow down living pace, just as the music of Stravinsky and Webern had foreshadowed modern business practice.

The Architect as Acoustic Engineer in Antiquity

in a moment I will have some harsh things to say about modern architects’ abilities as acoustic designers. But to prepare the case against them it is ecessary to consider them in comparison with their ancient colleagues. Architects of the past knew a great deal about the effects of sound and worked with them positively, while their modern descendants know little about the effects of sound and are thus reduced to contending with them negatively.

The early builders built with ear as well as eye. The exceptional acoustics of the Greek amphitheaters, of which the Asclepius theater at Epidaurus is perhaps the best example, do not prove that acoustics had been totally mastered in ancient Greece, but they do show that a general philosophy of building existed in which acoustic considerations helped determine the form and siting of the structure. In the empty amphitheater at Epidaurus the sound of a pin dropping can be heard distinctly in each of the 14,000 seats—an assertion I have put to the test. That Greek actors were frequently depicted wearing masks with megaphones attached to their mouthpieces does not show that ancient theater acoustics were a failure but merely that Greek theater audiences were probably unruly.

The most beautiful building I have ever experienced is the Shah Abbas Mosque in Isfahan (completed

AD

. 1640), sumptuously elegant in gold and azure tile, with its famous sevenfold echo under the main cupola. One hears this echo seven times perfectly when standing directly under the apex of the cupola; standing a foot to either side one hears nothing. Experiencing this remarkable event one cannot help thinking that the echo was no mere byproduct of visual symmetry but was intentionally engineered by designers who knew perfectly well what they were doing and perhaps even used the echo principle in determining the parabolic features of their cupolas.

Something similar apparently exists in the Temple of the Ruler of the Universe in Peking. The actual temple is a circular building, surrounded by a circular wall, inside which are two rectangular buildings, probably indicating the place of the earth within the universe. If a person stands in the center of the site and claps, a series of rapid echoes is heard, caused by reflections from the outer wall. But by moving slightly off-center the echoes will change completely, because only every second reflection will return to the point of origin. In other places near the center, the acoustical conditions are even more complicated, and the echoes will change with even the slightest shift in the placement of the sound-producer. Within this structure it is also possible for persons to converse naturally at great distance when standing just inside the circular wall, for this flat hard-surfaced wall reflects sound around its inner surface with a minimum of transmission loss.

Unfortunately, we have no accounts of how or why acoustic specialties were incorporated into ancient buildings such as these, but since all ancient cultures were strongly auditory, they were quite probably conceived deliberately to express divine mysteries, and at any rate they were certainly not the unpredictable consequences of blueprint accidents. W. C. Sabine, the best architectural acoustician of modern times, studied the"whispering galleries” of some newer buildings: the Dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, Statuary Hall in the Capitol at Washington, the vases in the Salle des Cariatides in the Louvre in Paris, St. John Lateran in Rome and the Cathedral of Girgenti. Sabine’s conclusion: “It is probable that all existing whispering galleries, it is certain that the six more famous ones, are accidents; it is equally certain that all could have been predetermined without difficulty, and like most accidents would have been improved upon.” But these were expressions of a time which was exchanging its ears for its eyes, of a time when the engineering drawing was becoming the prerequisite of architectural thought. This was not so in the Asclepius Theater, in the Shah Abbas Mosque or in the Temple of the Ruler of the Universe. They cannot be “improved upon,” for they resulted from the synchronous interaction of

the eye and the ear

.

Among the classical papers on architecture none is more voluminous or respected than the ten books of

De Architectura

by the Roman Vitruvius, which date from about 27 B.C. Book V adequately demonstrates the writer’s familiarity with the importance of acoustics, especially in the building of theaters, where, following an extensive exposition of the principles of the Greek science, he discusses the employment of sounding vases in theaters to enhance sound production. Vitruvius writes:

Hence in accordance with these enquiries, bronze vases are to be made in mathematical ratios corresponding with the size of the theatre. They are to be so made that, when they are touched, they can make a sound from one to another of a fourth, a fifth and so on to the second octave. Then compartments are made among the seats of the theatre, and the vases are to be so placed there that they do not touch the wall, and have an empty space around them and above. They are to be placed upside down. On the side looking towards the stage, they are to have wedges put under them not less than half a foot high. Against these cavities openings are to be left in the faces of the lower steps wo feet long and half a foot high. …

Thus by this calculation the voice, spreading from the stage as from the centre and striking by its contact the hollows of the several vases, will arouse an increased clearness of sound, and, by the concord, a consonance harmonising with itself.

That these techniques were not special to Vitruvius, we know from the author’s own assertion: “Someone will say, perhaps, that many theatres are built every year at Rome without taking any account of these matters. He will be mistaken in this.”

These sounding vases were what we now call Helmholtz resonators, and whether or not they originated in Rome, they appear to have been widely used throughout Europe and Asia in the following centuries. They were used in the Shah Abbas Mosque of Isfahan and have been found built into the walls in a number of old Scandinavian, Russian and French churches. In the case of the European churches, the principle appears not o have been completely understood, for the sounding vases do not exist there in sufficient number to produce any noticeable acoustic effect. But a recent discovery of a large quantity of sounding vases (fifty-seven in all) in the small fifteenth-century abbey church at Pleterje, between Ljubljana and Zagreb, shows that the tradition was accurately understood by the Yugoslavian builders, for the double resonance system employed in this case resulted in a high absorption over a broad frequency band from 80 to 250 hertz, an area in which the reverberation time in brick chapels is normally much too long.

From Positive to Negative Acoustic Design

Architecture, like sculpture, is at the frontier between the spaces or sight and sound. Around and inside a building there are certain places that function as both visual and acoustic action points. Such points are the foci of parabolas and ellipses, or the intersecting corners of planes; and it is from here that the voice of the orator and musician will be heard to best advantage. It is here also that the metaphorical voices of sculptured figures will find their true position, not on the metope or tympanum or porch.

Old buildings were thus acoustic as well as visual spectacles. Into the handsome spaces of the well-designed building, orators and musicians were attracted to create their strongest works; there they gained a reinforcement denied them in most natural settings. But when such buildings ceased to be the acoustic epicenters of the community and became merely functional spaces for silent labor, architecture ceased to be the art of positive acoustic design.