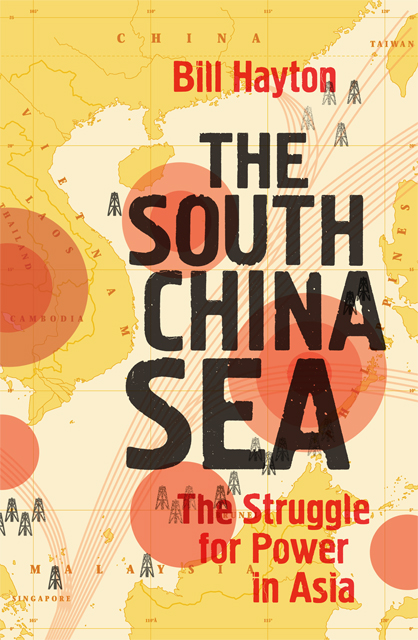

The South China Sea

Read The South China Sea Online

Authors: Bill Hayton

Copyright © 2014 Bill Hayton

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact:

U.S. Office:

[email protected]

www.yalebooks.com

Europe Office:

[email protected]

www.yalebooks.co.uk

Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd

Printed in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014944966

ISBN 978-0-300-18683-3

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book was begun while I was working in the BBC in London and finished while I was seconded to the reform of Myanmar Radio and Television. It is dedicated to my friends and colleagues in two very different newsrooms.

“News is what somebody does not want you to print. All the rest is advertising.”

Anon (though attributed to many people)

Contents

1

Wrecks and Wrongs: Prehistory to 1500

3

Danger and Mischief: 1946 to 1995

4

Rocks and Other Hard Places: the South China Sea and International Law

5

Something and Nothing: Oil and Gas in the South China Sea

6

Drums and Symbols: Nationalism

7

Ants and Elephants: Diplomacy

8

Shaping the Battlefield: Military Matters

9

Cooperation and its Opposites: Resolving the Disputes

Acknowledgements and Further Reading

The South China Sea – known as the East Sea in Vietnam and the West Philippine Sea in the Philippines.

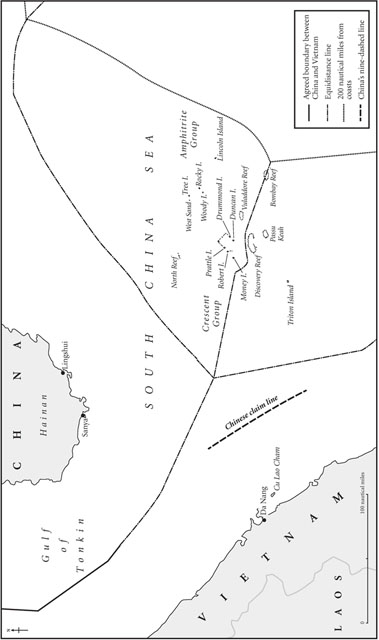

The Paracel Islands: occupied by China, which calls them the Xisha, but claimed by Vietnam, which calls them the ‘Hoang Sa.

The Spratly Islands, known as the Nansha in China, the Truong Sa in Vietnam and the Kalayaan Island Group in the Philippines.

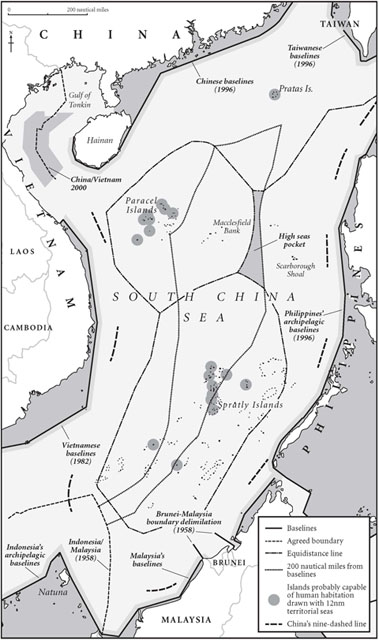

The South China Sea showing islands potentially large enough to be considered ‘capable of sustaining human habitation or economic life’. The cartographer has drawn these islands with 12 nautical mile territorial seas and hypothetical Exclusive Economic Zones. The EEZs are shown with their maximum effect – half way between the island and the nearest coastline. Recent ICJ judgements suggest the line would be drawn closer to the islands. The map also shows how China's ‘U-shaped line’ claim cuts into every littoral country's EEZ drawn from their coastline. (Based on a map drawn by I Made Andi Arsana, Lecturer at the Department of Geodetic and Geomatic Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia.)

Introduction

O

NE DAY IN

the future, a pair of fishing boats might set out from the Philippine island of Luzon, heading west into the open sea. They will set a course for a coral atoll once named after the harbour they have just left, the Bajo de Masingloc. Over the past 300 years the atoll has had many names. The Spanish also called it Maroona Shoal, the British called it Scarborough Shoal, nationalist Chinese named it Min'zhu – Democracy – Reef, Communist Chinese renamed it Huangyan – Yellow Rock – and, most recently and least appropriately, nationalist Filipinos baptised it Panatag – Tranquil – Shoal. When they arrive, the crews will see very little: just the summit of a mountain that surges from the sea floor 4,000 metres below. A single tower of rock standing alone in the South China Sea.

If it were only 3 metres shorter, the mountain would be unremarkable, aside from the danger it would pose to passing ships. But even at high tide a few rocks break the surface, each just about large enough to stand on. And since the official definition of an island is ‘a naturally formed area of land, surrounded by water, which is above water at high tide’, those few metres make all the difference.

1

Recognised possession of an island gives the owner rights to the sea, to the fish swimming around it and to the minerals that may lie on or below the seabed. More recently, possession has come to mean much more. For some, it has become the difference between pride and humiliation, between the status of great power and also

ran. Which is why on this day in the future the fishing boats are trying to reach it.

On this hypothetical day, the boats are carrying flag-waving Filipinos: members of Congress, former military officers and veteran street protestors. Under cover of darkness they try to slip past a ship of the China Coast Guard: there to prevent just such an incursion. They almost make it. While the Chinese ship is patrolling the far end of the atoll they dash for the entrance to the lagoon. It's a risky move. The entrance is 350 metres wide but currents and waves push the craft almost onto the reef. Just as they're getting close they hear a shot and the night is turned bright by a flare overhead. A small boat is barrelling towards them at high speed and a loud-hailer barks a warning in English: ‘This is Chinese territory since ancient times. You must leave this area immediately. Leave or we will be forced to take action against you.’ But the Filipinos press on: they're almost inside the lagoon. Another warning: ‘If you do not leave immediately, we will take armed action against you. Turn your boats around.’ With the first boat just 10 metres from the lagoon mouth, another shot. This time it's not a flare. Bullets splash in the water.

On the fishing boats the military men are urging the captains to press on. They've been under fire before. They're not intimidated. They've come too far to give up now. They will plant their flags on this piece of Philippine territory. Another burst of fire rakes the deck. A crewman is killed; a congressman is hit in the shoulder and two other activists seriously wounded. But the boats are inside the lagoon now – and the military men produce their own weapons and fire back. The Chinese speedboat backs off, but the mother ship is now blocking the only exit from the lagoon. On board the bullet-riddled boat there is panic. First aid is given and congressional assistants use satellite phones to call in help and favours. Live interviews are given to breathless TV news anchors. In Manila, crowds form around the Ministry of Defence and the Chinese consulate, demanding action. In Beijing, another crowd hurls rocks at the Philippine embassy, online wars break out, websites are hacked and defaced. Everyone is calling for action. The Chinese government refuses to allow the fishing boats to leave the lagoon, saying they have entered its territory illegally and must be dealt with by the law. The Philippine government demands the release of the boats and all on board and despatches its largest warship, the BRP

Gregorio del Pilar,

to the scene.

The Chinese don't back down, so the

Gregorio

fires a warning shot. No response. Philippine naval special forces are sent to board the Chinese ship, fist-fights break out on the bridge, tear gas is used and someone starts shooting. Then two Chinese jets try to strafe the

Gregorio

. They miss, but it's the last straw: having pulled out the special forces, the

Gregorio

shells the Chinese, hitting the ship near the stern. It limps away and the Filipino activists exit the lagoon and are hauled aboard the

Gregorio

for medical treatment. The provocation is too much for Beijing to bear. While the world urges calm and restraint an expeditionary force sets sail from Sanya, the headquarters of the South China Sea fleet on Hainan Island.