The Story of the Romans (Yesterday's Classics) (28 page)

As Maximian had retired at the same time as Diocletian, the Roman Empire was now divided between Galerius and Constantius, who were known as emperors of the East and of the West, respectively. Constantius, having obtained the West for his share, went to Britain to suppress a revolt. He died at York, and his son Constantine became emperor in his stead.

Constantine's claim to the empire was disputed by several rivals; but the strongest among them was Maxentius, who ruled Italy and had a large army. On his way to meet him, Constantine became a Christian, thanks to a miracle which the ancient writers relate about as follows.

At noontide, on the day before his battle with Maxentius, Constantine and his army were startled by a brilliant cross, which suddenly appeared in the sky. Around the cross were the Greek words meaning, "By this sign conquer."

Constantine was so moved by this vision that he made a vow to become a Christian if he won the victory. He also ordered a new standard, called a Labarum, which bore the cross, and the inscription he had seen in the skies. This was always carried before him in battle.

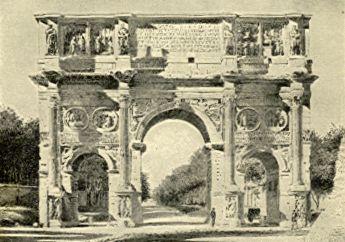

Arch of Constantine

The two armies met near Rome. Maxentius was defeated, and Constantine entered the city in triumph. In memory of his victory a fine arch was built, which is standing still, and is always called the Arch of Constantine.

The First Christian Emperor

T

HE

vow which Constantine had made was duly kept, to the great satisfaction of his mother Helena, who was a very devout Christian. Constantine ordered that the Christians should have full liberty to worship as they pleased; and after a time he himself was baptized. He also forbade that criminals should be put to death on a cross, as it had been sanctified by Christ; and he put an end to all gladiatorial shows.

Constantine at first shared the power with Licinius, but he and his colleague quarreled on matters of religion. They soon came to arms, and we are told that when they stood opposed to each other they loudly called upon their gods.

As Constantine won the victory, he declared that his God was the most worthy of honor; and he established the Christian Church so securely that nothing has ever been able to overthrow it since then. By his order, all the learned Christians came together at Nicæa to talk about their religion, and to find out exactly what people should believe and teach. Here they said that Arius, a religious teacher, had been preaching heresy; and they banished him and his followers to a remote part of the empire.

Constantine soon changed the seat of the government to Byzantium, which was rebuilt by his order, and received the name of Constantinople, or city of Constantine. Because he accomplished so much during his reign, this emperor has been surnamed the Great, although he was not a very good man.

During the latter part of his reign, there were sundry invasions of the barbarians; and Constantine, who was a brave warrior, is said to have driven them back and treated them with much cruelty. He died of ague at Nicomedia, leaving his empire to his three sons; and his remains were carried to Constantinople, so that he might rest in the city which bore his name.

Soon after the death of Constantine, who is known in Roman history as the first Christian emperor, his three sons began to quarrel among themselves. The result was a long series of civil wars, in which two of the brothers were killed, leaving the whole empire to the third—Constantius II.

The new emperor, needing help, gave his cousin Julian the title of Cæsar, and placed him in charge of Gaul. As Julian belonged to the family of Constantine, he was of course a Christian. He was a very clever youth, and had been sent to Athens to study philosophy.

While there, he learned to admire the Greek philosophers so much that he gave up Christianity, and became a pagan. On account of this change in religion, he is generally known by the surname of the Apostate. We are told, also, that he spent much time in studying magic and alchemy, a science which was supposed to teach people how to change all metals into gold.

Julian the Apostate gave up his studies with regret, to share the cares of government. While in Gaul, he learned to be an excellent general, and drove back the barbarians several times. He lived for a while in Lutetia, the present city of Paris, and here he built Roman baths whose ruins can still be seen.

The Roman Empire Divided

J

ULIAN

became emperor when Constantius II. died. As soon as the authority was entirely in his own hands, he ordered that the Christian churches and schools should all be closed, and encouraged the people to worship the old pagan gods.

All the soldiers in his army were forced to give up Christianity, under penalty of being dismissed; and he made an attempt to rebuild the temple at Jerusalem so as to prove to the Christians that the prophecy of Christ was not to be believed. But an earthquake frightened his builders away from the work, and a war against the Persians prevented its ever being renewed.

During this campaign, Julian was mortally wounded, and he is said to have died exclaiming: "Thou hast conquered, Galilean!" The emperor's body was carried to Tarsus, and buried there; and, as Julian had appointed no successor, the army at once gave the empire to one of his officers, named Jovian.

A good man and a fervent Christian, Jovian quickly reestablished the Christian religion. His reign, however, was very brief, and he was succeeded by two brothers, Valentinian and Valens, who again divided the Roman world into two parts, intending to make a final separation between the empires of the East and the West (A.D. 364).

Valentinian kept back the northern barbarians as long as he lived, but after his death Valens was forced to allow the Goths to settle in Thrace. Here they found some of their brothers who had been converted to Christianity by the efforts of Ulfilas, a learned man, who wrote a translation of the Bible for them in their own Gothic language.

Valens failed to keep many of the promises which he had made to the Goths, and they became so angry that they revolted and killed him at Hadrianople.

The next emperor of the East was Theodosius. He was so good a general, and still so very just, that he soon succeeded in making peace with the Goths, many of whom entered his army and became Roman soldiers.

After years of continual warfare against the barbarians and the emperors of the West, Theodosius became sole ruler of the whole Roman Empire, and thus won the surname of Great. During his reign, he induced his subjects to renounce all the pagan gods except Victory, whom they would not consent to give up.

Many reforms were also made among the Christians, the Arians were again said to be heretics, and then the true Christians for the first time took the name of Catholics. Theodosius was the last Roman emperor whose sway extended over the whole empire; and when he died he left the rule of the East to his son Arcadius, and of the West to his son Honorius.

An Emperor's Penance

T

HEODOSIUS

was, as we have seen, an excellent emperor, and we are told that there is but one stain on his memory,—the massacre at Thessalonica.

The people of that city once revolted, because the soldiers had arrested one of their favorite chariot drivers, who had failed to obey the laws. In his rage at hearing of this revolt, Theodosius commanded that all the inhabitants of Thessalonica should be killed. Men, women, and children were accordingly butchered without mercy; but when the deed was done, the emperor repented sorely of his cruelty.

He then went to St. Ambrose, a priest who had vainly tried to disarm his anger. Humbly begging pardon for his cruelty, he asked permission to come into the Church once more. St. Ambrose, however, would not grant him forgiveness until Theodosius had done public penance for his sin.

Thus, you see, when the Christian emperors did wrong, they were publicly reproved by the priests, whose duty it was to teach men to do good and to love one another.

Both sons of Theodosius were mere boys when they were called by their father's death to take possession of the empires of the East and of the West. For a while, however, the barbarians dared not invade Roman territory, for they had not yet forgotten how they had been conquered by Theodosius.

The empire of the West in time became the weaker and the smaller of the two; for the Caledonians in Britain, the Germans along the Rhine, the Goths and Huns along the Danube, and the Moors in Africa were little by little invading its territory and taking possession of its most exposed cities.

As the two princes were themselves too young to govern, the power was wielded by their guardians, Stilicho and Rufinus, who quarreled and finally fought against each other. The national jealousy which had always existed between the Greeks and the Latins was increased by these quarrels between the two ministers; and it did not come to an end even when Rufinus was caught in an ambush and slain.

When the Goths saw that the empires of the East and the West were too busy quarreling with each other to pay any attention to them, they suddenly marched into Greece under Alaric.

The Greeks, in terror, implored Stilicho to hasten to their rescue. He came, and won a victory over the Goths; but, instead of following up his advantage, he soon returned to Italy. The Goths, seeing this, soon followed him thither, and laid siege to Milan.

Stilicho raised an army as quickly as possible, and defeated the Goths on the same field where Marius had once conquered the Cimbri. But the Goths, although defeated, secured favorable terms before they withdrew.

Honorius, the emperor of the West, had been very badly frightened by the appearance of the Goths in Italy. In his terror, he changed his residence to the city of Ravenna, where he fancied that he could better defend himself if they attacked him.

Sieges of Rome

T

HE

Goths had scarcely gone when some other barbarians made an invasion, and this time Florence was besieged. The town held out bravely until Stilicho could come to its rescue, and then the invaders were all captured, and either slain or sold into slavery.

Shortly after this, however, Stilicho was murdered by the soldiers whom he had so often led to victory. The news of trouble among the Romans greatly pleased Alaric, the King of the Goths; and, when the money which Stilicho had promised him failed to come, he made a second raid into Italy.

This time Alaric swept on unchecked to the very gates of Rome, which no barbarian army had entered since the Gauls had visited it about eight hundred years before. The walls were very strong, and the Goths saw at once that the city could not be taken by force; but Alaric thought that it might surrender through famine.

A blockade was begun. The Romans suffered greatly from hunger, and soon a pestilence ravaged the city. To bring about the departure of the Goths, the Romans finally offered a large bribe; but, as some of the money was not promptly paid, Alaric came back and marched into Rome.

Again promises were made, but not kept, and Alaric returned to the city a third time, and allowed his men to plunder as much as they pleased. Then he raided all the southern part of Italy, and was about to cross over to Sicily, when he was taken seriously ill and died.

Alaric's brother, Adolphus, now made a treaty with the Romans, and married Placidia, a sister of Honorius. He led the Goths out of Italy, across France, and into Spain, where he founded the well-known kingdom of the Visigoths.

When Adolphus died, his widow, Placidia, married a noble Roman general; and their son, Valentinian III., succeeded his uncle Honorius on the throne of the Western empire. During his reign there were civil wars, and his territory was made still smaller; for Genseric, King of the Vandals, took possession of Africa.

The Huns, in the mean while, had seized the lands once occupied by the Goths; and they now became a united people under their king, Attila, who has been called the "Scourge of God." By paying a yearly tribute to these barbarians, the Romans managed for a time to keep them out of the empire, and induced them thus to pursue their ravages elsewhere.

But after becoming master of most of the territory beyond the Danube and the Rhine, Attila led his hordes of fierce Huns and other barbarians, numbering more than seven hundred thousand men, over the Rhine, and into the very heart of France. There, not far from Châlons, took place one of the fiercest and most important battles of Europe.

Attila was defeated with great loss by the Roman allies; but the next year he led his army over the Alps and down into the fertile plains of Italy. Here Pope Leo, the bishop of Rome, met Attila and induced him to spare Rome and leave Italy, upon condition that the sister of Valentinian should marry him.

This marriage never took place, however, for Attila returned home and married a Gothic princess named Ildico. We are told that she murdered him, on her wedding night, to avenge the death of her family, whom Attila had slain; but some historians say that the king died from bursting a blood vessel.