The Story of the Romans (Yesterday's Classics) (8 page)

O

F

course all the spectators cheered the victorious general when he thus marched through Rome in triumph; and they praised him so highly that there was some danger that his head would be turned by their flattery.

To prevent his becoming too conceited, however, a wretched slave was perched on a high seat just behind him. This slave wore his usual rough clothes, and was expected to bend down, from time to time, and whisper in the conqueror's ear:

"Remember you are nothing but a man."

Then, too, a little bell was hung under the chariot, in such a way that it tinkled all the time. This ringing was to remind the conqueror that he must always be good, or he would again hear it when he was led to prison, or to gallows; for the passage of a criminal in Rome was always heralded by the sound of a bell.

If the victory was not important enough to deserve a triumph, such as has just been described, the returning general sometimes received an ovation. This honor was something like a triumph, but was less magnificent, and the animal chosen as the victim for sacrifice was a sheep instead of a bull.

The Roman who received an ovation came into the city on foot, wearing a crown of myrtle, and escorted by flute players and other musicians. The procession was much smaller than for a triumph, and the cheers of the people were less noisy.

Now you must not imagine that it was only the generals and consuls who were publicly honored for noble deeds. The Romans rewarded even the soldiers for acts of bravery. For instance, the first to scale the walls of a besieged city always received a crown representing a wall with its towers. This was well known as a mural crown, and was greatly prized. But the man who saved the life of a fellow-citizen received a civic crown, or wreath of oak leaves, which was esteemed even more highly.

All those who fought with particular bravery were not only praised by their superiors, but also received valuable presents, such as gold collars or armlets, or fine trappings for their horses. The soldiers always treasured these gifts carefully, and appeared with them on festive occasions. Then all their friends would admire them, and ask to hear again how they had been won.

All Roman soldiers tried very hard to win such gifts. They soon became the best fighters of the world, and are still praised for their great bravery.

The Defense of the Bridge

V

ALERIUS

,

as you have seen, received the honors of the first triumph which had ever been awarded by the Roman Republic. By the death of Brutus, also, he was left to rule over the city alone. As he was very rich, he now began to build himself a new and beautiful house.

The people of Rome had never seen so handsome a dwelling built for a private citizen; so they began to grow very uneasy, and began to whisper that perhaps Valerius was going to try to become king in his turn.

These rumors finally came to the ears of the consul; and he hastened to reassure the people, by telling them that he loved Rome too well to make any attempt to change its present system of government, which seemed to him very good indeed.

Tarquin, as we have seen, had first gone to the people of Veii for help; but when he found that they were not strong enough to conquer the Romans, he began to look about him for another ally. As the most powerful man within reach was Porsena, king of Clusium, Tarquin sent a message to him to ask for his aid.

Porsena was delighted to have an excuse for fighting the Romans; and, raising an army, he marched straight towards Rome. At his approach, the people fled, and the senate soon saw that, unless a speedy attempt was made to check him, he would be in their city before they had finished their preparations for defense.

The army was therefore sent out, but was soon driven back towards the Tiber. This river was spanned by a wooden bridge which led right into Rome. The consul at once decided that the bridge must be sacrificed to save the city; and he called for volunteers to stand on the other side and keep Porsena's army at bay while the workmen were cutting it down.

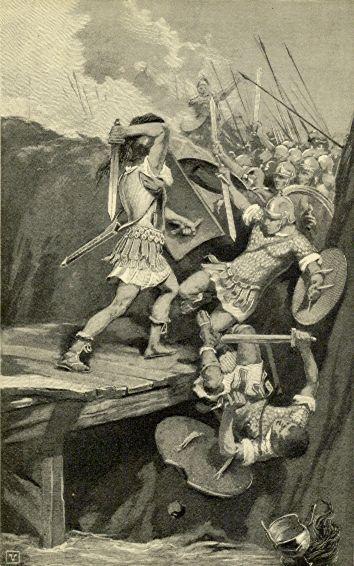

A brave Roman, called Horatius Cocles, or the One-eyed, because he had already lost one eye in battle, was the first to step forward and offer his services, and two other men promptly followed him. These three soldiers took up their post in the narrow road, and the rest of the Romans hewed madly at the bridge.

The two companions of Horatius, turning their heads, saw that the bridge was about to fall; so they darted across it, leaving him to face the armed host alone. But Horatius was too brave to flee, and in spite of the odds against him, he fought on until the bridge crashed down behind him.

Horatius at the Bridge

As soon as the bridge was gone there was no way for the enemy to cross the river and enter Rome. Horatius, therefore ceased to fight, and, plunging into the Tiber, swam bravely to the other side, where his fellow-citizens received him with many shouts of joy.

In reward for his bravery they gave him a large farm, and erected a statue in his honor, which represented him as he stood alone near the falling bridge, keeping a whole army at bay.

The Burnt Hand

H

INDERED

from marching into Rome as easily as he had expected, Porsena prepared to surround and besiege it. The prospect of a siege greatly frightened the people; for they had not much food in the city, and feared the famine which would soon take place.

The Romans were, therefore, placed on very short rations; but even so, the famine soon came. All suffered much from hunger,—all except Horatius Cocles, for the starving Romans each set aside a small portion of their scanty food, and bade him accept it. It was thus that they best showed their gratitude for the service he had done them, for they proved that they were brave enough to deny themselves in order to reward him.

The Romans were still unwilling to surrender, but they feared that Porsena would not give up until he had taken possession of the city. Some of the young men, therefore, made up their minds to put an end to the war by murdering him. A plot was made to kill the King of Clusium by treachery; and Mucius, a young Roman, went to his camp in disguise.

When Mucius came into the midst of the enemy, he did not dare ask any questions, lest they should suspect him. He was wandering around in search of Porsena, when all at once he saw a man so splendidly dressed that he was sure it must be the king. Without waiting to make sure, he sprang forward and plunged his dagger into the man's heart.

The man sank lifeless to the ground, but Mucius was caught and taken into the presence of Porsena. The king asked him who he was, and why he had thus murdered one of the officers. Mucius stood proudly before him and answered:

"I am a Roman, and meant to kill you, the enemy of my country."

When Porsena heard these bold words, he was amazed, and threatened to punish Mucius for his attempt by burning him alive. But even this threat did not frighten the brave Roman. He proudly stepped forward, and thrust his right hand into a fire that was blazing near by. He held it there, without flinching, until it was burned to a crisp; and then he said:

"Your fire has no terrors for me, nor for three hundred of my companions, who have all sworn to murder you if you do not leave Rome."

When Porsena heard these words, and saw the courage that Mucius displayed, he realized for the first time how hard it would be to conquer the Romans, and made up his mind to make peace. So he sent Mucius away without punishing him, for he admired the courage of the young man who loved his country so truly.

Mucius returned to Rome, and there received the nickname of Scævola, or the Left-handed. Soon after, Porsena began to offer peace, and the Romans were only too glad to accept it, even though they had to give him part of their land, and send some of their children into his camp as hostages.

Porsena treated these young people very kindly; but they soon grew homesick, and longed to return home. One of the hostages, a beautiful girl named Clœlia, was so anxious to go back to Rome that she sprang upon a horse, plunged into the Tiber, and boldly swam across it. Then she rode proudly into the city, followed by several of her companions, whom she had persuaded to imitate her.

The Romans were delighted to see their beloved children again, until they heard how they had escaped. Then they sadly told the hostages that they would have to return to Porsena. Clœlia and her companions objected at first; but they finally consented to go back, when they understood that it would be dishonorable if the Romans failed to keep the promises they had made, even to an enemy.

The king, who had witnessed their escape with astonishment, was even more amazed at their return. Full of admiration for Clœlia's pluck and for the honesty of the Romans, he gave the hostages full permission to go home, and left the country with all his army.

The Twin Gods

T

ARQUIN

had now made two unsuccessful attempts to recover the throne. But he was not yet entirely discouraged; and, raising a third army, he again marched toward Rome.

When the senate and consuls heard of this new danger, they resolved to place all the authority in the hands of some one man who was clever enough to help them in this time of need. They therefore elected a new magistrate, called a Dictator. He was to take command of the army in place of the consuls, and was to be absolute ruler of Rome; but he was to hold his office only as long as the city was in danger.

The first dictator immediately took command of the army, and went to meet Tarquin. The two forces came face to face near Lake Regillus, not very far from the city. Here a terrible battle was fought, and here the Romans won a glorious victory. Their writers have said that the twin gods, Castor and Pollux, came down upon earth to help them, and were seen in the midst of the fray, mounted upon snow-white horses.

When the fight was over, and the victory gained, these gods vanished from the battlefield; but shortly after, they came dashing into Rome, and announced that the battle was won. Then they dismounted in the Forum, in the midst of the people, watered their horses at the fountain there, and suddenly vanished, after telling the Romans to build a temple in their honor.

Full of gratitude for the help of the twin gods, without whom the battle would have been lost, the Romans built a temple dedicated to their service. This building was on one side of the Forum, on the very spot where the radiant youths had stood; and there its ruins can still be seen.

Roman Forum and Temple of Castor and Pollux

The Romans were in the habit of calling upon these brothers to assist them in times of need; and in ancient tombs there have been found coins bearing the effigy of the two horsemen, each with a star over his head. The stars were placed there because the Romans believed that the twin gods had been changed into two very bright and beautiful stars.

It is said that Tarquin managed to escape alive from the battle of Lake Regillus, and that he went to live at Cumæ, where he died at a very advanced age. But he never again ventured to make war against the Romans, who had routed him so sorely.

The old consul Valerius continued to serve his native city, and spent his money so lavishly in its behalf that he died very poor. Indeed, it is said that his funeral expenses had to be paid by the state, as he did not leave money enough even to provide for his burial.

The Wrongs of the Poor

N

OW

that the war against Tarquin was over, the Romans fancied that they would be able to enjoy a little peace. They were greatly mistaken, however; for as soon as peace was made abroad, trouble began at home.

There were, as you have already heard, two large classes of Roman citizens: the patricians, or nobles, and the plebeians, or common people. They remained distinct, generation after generation, because no one was allowed to marry outside his own class.

The patricians alone had the right to be consuls and senators; they enjoyed many other privileges, and they owned most of the land.