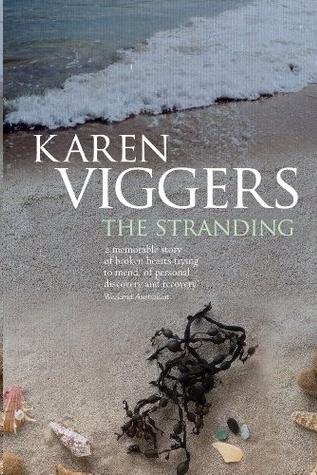

The Stranding

Karen Viggers was born in Melbourne, Australia, and grew up in the Dandenong Ranges riding horses and writing stories. She studied Veterinary Science at Melbourne University, and then worked in mixed animal practice for five years before completing a PhD at The Australian National University, Canberra, in wildlife health. Since then she has worked on a wide range of Australian native animals in many different natural environments. She lives in Canberra with her husband and two children. She works part-time in veterinary practice, provides veterinary support for biologists studying native animals, and writes in her spare time.

KAREN

VIGGERS

THE STRANDING

ALLEN

ALLEN

&

UNWIN

First published in 2008

This edition published in 2009

Copyright © Karen Viggers 2008

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian

Copyright Act 1968

(the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: [email protected]

Web:

www.allenandunwin.com

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

The stranding/author, Karen Viggers.

ISBN 978 1 74175 773 6 (pbk.).

A823.4

Typeset in 11/13.5 pt Bembo by Bookhouse, Sydney

Printed in Australia by McPherson’s Printing Group

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For David

For his infinite love, patience and support

He left the house in the eerie light of the moon and walked barefoot

to the end of the road. Here the cliffs fell sharply into the sea and

most nights the waves foamed over the rocks and crashed against

the walls. But tonight was calm, and the sea collided with the rocks

less violently, and despite the constant movement everything seemed

unusually still. The moon sailed large and round, illuminating the

wisps of cloud that drifted across the sky.

There was something else in the night. He could feel it. A

presence. He was sure it had a name, and he was not afraid of it.

Looking out across the flickering silver sea he watched the swell

rolling in, ever moving, rising, falling, rising, falling. He felt

his breathing slowing, deepening. The rhythm calmed him. The

rhythmic emptiness of the endless sea.

Then he heard it. A loud huffing sound. Below and not far

out. His eyes swept over the surface of the water, seeking. There

must be something . . . The water slid quietly, rolling in towards

the cliffs. Then he could see it, the smooth back of a whale, slick

and glistening, black and silver, as the sea rippled over it. An

exhalation came again. He could see the vapour spout this time,

drifting fine spray lit by the moon. Then another, a smaller puff,

a calf, wallowing alongside. His heart raced. He wondered if they

had seen him too, whether they knew he was there, watching them,

alive and present in the night, bearing the weight of existence.

For a long time he stood there, breathing with the whales,

watching the sea slide over their sleek backs, listening to the slow

puffs of their restfulness. In the long, moving quiet, he found emptiness,

and the joy contained within it. He dwelled in the essence of

now, away from pain, until he was cold and soaked with dew.

Contents

A month after he moved to Wallaces Point, Lex Henderson burned all his clothes. He burned every last item, except what he was standing in. And he did it deliberately. It was an irrational moment and nothing could have stopped him.

He’d arrived with wounds that were deep but invisible. He’d packed his Sydney life into a suitcase and driven south, leaving chaos behind, but also carrying it within. As the highway hours stretched behind him, the trepidation and doubt that had followed him from the city began to ease, and his hands rested more steadily on the wheel. When, finally, the Volvo shuddered to a halt on the grass outside his new home, the sound of the sea entered him and he was calm.

He spent the first few weeks at Wallaces Point drifting along the beach by day and drinking himself into oblivion at night. He passed the daylight hours trying to erase the ugliness of the night before, and the night trying to erase the past four months when his life had turned upside down. Daytime, it was easy to immerse himself in the lonely wild world of the beach. The wind swirled through his soul, the spring sun warmed his head, and he walked, leaving footprints in the sand then sitting up on the rocks to watch them dissolve as the tide crept back up the beach.

In those first days, he saw large things, like the waves shaping the beach, the swans on the lagoon, the crushing blue of the enormous sky. Then, gradually, over hours and days, his focus sharpened and he began to see other things: the rippling patterns left in the sand by the receding water, a sea eagle floating on the breeze above the cliffs, sooty oystercatchers poking among the rocks, honeyeaters scattering in dogfights over the heath.

After that, patterns started to emerge, like the time of day the eagle appeared and where it roosted in a skeletal tree on the headland, the timing of the tides, the gradation of sea creatures on the rocks, when to expect the honking of swans just after dusk as they flew low towards the lagoon. He watched the waters and learned to read the rips, sat for hours watching gannets fishing out to sea. Along the high tide mark he fossicked for seashells and rocks, tiny bird skulls, cuttlefish floats, driftwood, crab claws, tendrils of pink seaweed. On the rocks just below the cliffs, he spent hours sitting, watching the waves roll in. Over and over. From low tide to high. The roar and rhythm were just enough to anchor his sanity.

In the laundry cupboard he found a wetsuit and fins, and on calm days he took to the sea. After that first gasp of cold water trickling through the suit, he plunged out and bodysurfed, kicking like crazy down the waves, then pulsing with the thrilling rush of being picked up and surged towards the beach. The waves shot him skywards before dumping him in a tumbled confusion of foam and sand. It did him good, the physicality of it, striding out against the incoming waves and then swimming to catch their ride in.

But nights were not so easy.

Each evening, he went inside, scrubbed clean by the wind and the sky, and stood by the window, watching the light fading from the heaving face of the sea. His new home stood fifty metres from the finish of the road, flanked by waving grasses and the stiff skeletons of a few hardy banksias bent rigid by the onshore winds. It was the last house in the line and its elongated face of glass looked out over the cliffs and the slow roll of the sea. The house faced north, gathering light, and the windows stretched in front of him like a wide-angled lens, collecting as much sea as they could grasp. From where Lex stood, the view reached far and long, passing the hummock of the darkening headland and arcing east across the water to the murky horizon. Whoever had built the house had only two things in mind: glass and sea.

To Lex, it seemed the house was waiting, as if it was watching for something.

When the sun had set and the silver waters had sunk to grey then featureless black, Lex would sit on a cane chair in the lounge room, staring out into darkness, wondering what he had done in coming here. When he had first seen it, the house seemed neutral enough—all straight lines and simplicity, an open plan kitchen and living area, just the essential furniture: a wooden kitchen table, a cane couch and a few armchairs facing the sea. But sometimes he thought perhaps he could feel someone else in the house. Someone else lifting an old book from the shelf and leafing through the musty pages. Someone else staring at the photos on the walls of old boats and salted fishermen. It seemed that the house was reminiscing on a past that had nothing to do with him.

The bookshelves were laden with books he would never have bought. A few were potentially useful: seashore guides, fishing manuals, a tattered handbook of birds. The rest were of dubious interest; mainly cheap shiny-backed novels, a few biographies and a handful of old books about whaling. Each night, determined to avoid the stash of grog in the pantry, Lex would pull a book from the shelf and flick through it, trying not to feel the dark pressing in through the windows, trying not to feel his skin creeping with desire—the desire for the emptiness that came with the bottle. But soon his will would wither and, with shaking hands and bitter self-contempt, he’d find himself at the cupboard again, pulling out a glass, pouring a drink, enjoying the tart burn of whisky. And there he would be once again, rollicking in misery, drowning the flood of his thoughts, burying them in staggering inebriation. Another night lost.