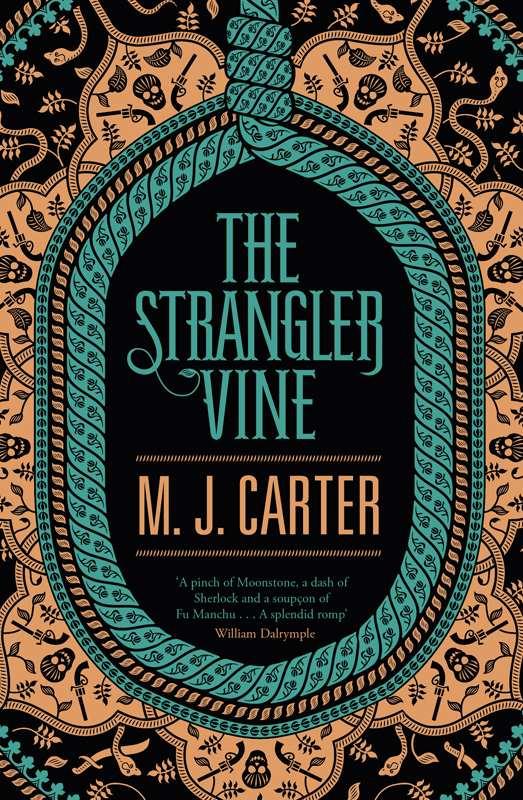

The Strangler Vine

Read The Strangler Vine Online

Authors: M. J. Carter

M. J. CarterTHE STRANGLER VINE

For my boys

The East India Company was launched in 1600 by a group of British merchants with ambitions to trade with the East. Over the next two centuries it built up its own private army and gradually gave up its trading interests in favour of taking over and ruling large parts of India, making money out of taxation and out of its monopoly in the opium trade with China. It became a peculiar mixture of private company and instrument of the British state, and was arguably the world’s first multinational.

By 1837 the Company dominated the subcontinent, controlling much of what is now India, Bangladesh and Nepal, with Calcutta as its capital. Within these borders there still existed many independent princely states, however, which struggled to find ways of existing alongside their powerful and hungry neighbour.

He stumbles out from the mango grove and at that moment the thick monsoon clouds, which colour the night a dull charcoal grey, shift. A sliver of moonlight shines through and he sees their bright, curved knives. Had the clouds not parted he would have blundered, laughing, straight through the gates, straight on to their blades.

As it is, he is in a befuddled haze, and pretty far gone. He has been alternately laughing disgustedly at himself, and seething at their crimes, their banality, their complacency. He has been imagining how he will pay them back.

Before he even understands what he has seen, an old instinct causes him to throw himself on to the sodden ground and scramble into the shadow of the tall, mud-spattered outer walls. The effort winds him and makes his chest hurt and his knees jar, and he wheezes. The sober part of him tries to quieten his breathing, noting now the soft patter of dripping water and understanding that the sounds of the monsoon have covered his approach. I have had too much, he thinks, and my bones are too old for such things.

He knows they are there for him. He can see two of them standing silent and still, behind the gates – gates that have always seemed too imposing for such a modest building. They are barefoot, their

dhotis

and turbans dyed or muddied so they blend into the dark, but the moon lights up their swords and the dark sheen of their young bodies. Another step and he would now be so much skewered meat. He winces at the coarseness of the phrase, and then suppresses the urge to giggle.

Awkwardly, he twists his neck to face the wall. Days of heavy rain have

penetrated the mortar and worked on cracks and holes. His hand shaking a little, he pulls away a little sand and gravel around one hole until it is large enough for him to see through into the compound.

Two lanterns on the grass give out a dim ambient light. Two men – he recognizes neither – armed with knives, speak in an intimate tone, too quiet for him to make sense of the words. Another comes on to the verandah, which means they have searched the house. One man’s knife is already dark and shiny with blood. The other lifts up something small and human-like, and dangles it by its long hairy arms. The watcher starts. A shiver runs through the creature’s limp body. He thinks he hears it whimper. The man tosses it up and catches it by its arms. Then, in a swift, practised, efficient movement, he places his hands round its neck and wrings it – a short, brutal twist – and the other man drives his knife into its chest. The watcher feels an unaccustomed pang of distress. He cannot remember the moment when the monkey parted company with him. It may have been hours ago. The assassin tosses the creature on to the ground, and with his comrade strolls over to the gates.

The one with the bloody knife speaks to the young guards. It is a Marathee dialect the watcher knows. He tells them to walk the walls once more. ‘He may be cowering in the shadows.’ The watcher knows he will never make it to the trees. The sober part of him feels, not precisely fear, but rather a sense of failure. They will kill me, and even if they do not find the papers, the truth will be lost. I will die and my grave will be unmarked and no one will know, and I will be forgotten. That thought is almost the worst.

As if in a dream, he watches the gate guard pad towards him, a knife at the ready in one hand, a long scarf in the other. The scarf. How appropriate, he thinks. Some fifteen yards from him, the guard crouches down and feels the ground where he cast himself on to the mud. He beckons the second guard. The watcher shrinks into the shadow of the wall, his mouth as dry as he can remember.

Step by step they draw closer to him, like some absurd parlour game. As they cover the last few yards he finds that, without realizing it, he has raised his arms in supplication, and is mildly disgusted by the intense desire he suddenly feels to live.

Part One

The palanquin lurched again to the left and I felt a fresh wave of nausea. I pushed the curtains aside in the vain hope of a current of cool air, and waited for the moment to pass. The perspiration started anew from my neck and my back, then soaked into the chafing serge of my second-best dress uniform. The dull, sour odour filled me with dejection. Our uniforms were not washed quite as often as I would have liked as it caused the fabric to disintegrate even more swiftly than it would otherwise have done.

‘

Khabadur you

soor

!

’ Take care, you swine! I shouted at the bearers, more to relieve my feelings than anything else.

‘William,’ said Frank Macpherson, ‘it will make no difference.’ Nor did it. There was no response, nor had I expected one.

Calcutta was hot. Not the infernal, burning heat of May, but rather the sticky, enervating sultriness of September. We were the only thing in the empty afternoon streets of Whitetown – it was too hot as yet for afternoon calls. It had been a relief when the monsoon had arrived in June, but the rain had persisted and persisted and now, after three months, the depredations of damp and standing water had become almost as tiresome as the raging heat before it. The city existed in a permanent state of soupy dampness. Books and possessions rotted. Diseases lurked in its miasma. Most of my acquaintances were down with fever or boils. At the Company barracks, where the walls gushed dirty brown water when it rained, there was said to be an outbreak of cholera.

Even in Tank Square, the grand heart of the city, one could smell

mould in the air. As our palanquin left the square to make for the Hooghly River ghats, it semed that even the adjutant birds perching one-legged on the parapets of Government House drooped in the heat.

‘I reckon the temperature is about ninety-five degrees,’ said Frank, who knew about such things.

We were on our way to Blacktown. I had been ordered – by the Governor General’s office, no less – to deliver a letter to a

civilian

called Jeremiah Blake. Frank had decided to come too, for he was curious and we had neither of us ever been into Blacktown proper: it was not the place for an English gentleman. Even on its outskirts, the sides of the roads were piled with filth and refuse and gave on to open ditches carrying all imaginable kinds of effluent. It was not unusual to find animal corpses rotting in the street and rats scuttling over one’s feet.

I was ambivalent about the commission. On the one hand, any recognition from the senior ranks of the Company was gratifying, and any relief from the tedium of barrack life to be welcomed. On the other, carrying a message to some civilian gone native felt like yet another demeaning, irksome, pointless task. Besides which, I had dipped deep into my cups the night before and was suffering greatly from the consequences.

‘Damn me, it is too much,’ I said, for the millionth time, pulling again at my collar to absolutely no effect. We shifted ourselves about a little. There was not quite room enough for two in the palanquin.

‘My, my, we are ill-tempered and sore-headed this morning,’ Frank said. ‘Must have been the fish. Certainly nothing to do with the gallon of claret, nor the ten pounds you lost.’

For nine months I had been kicking my heels in Calcutta, waiting to be summoned by a cavalry regiment in north Bengal which had shown no inclination to avail itself of my services, and I was not far off hating the city. One might have supposed that being an officer in the army of the Honourable East India Company would have its compensations. But after nine months they seemed dispiritingly few, while its deficiencies were unignorable: the monstrous

climate, the casual barbarities of the native population and the stiff unfriendliness of the European society. Calcutta was a city in thrall to form, status and wealth, and Frank and I were at the bottom of the pile. Keeping up appearances, whatever the expense, appeared to be the most pressing duty. We drilled in the mornings before it got too hot, and studied for the Hindoostanee diploma – which no one took very seriously. Most of the officers got by with soldier bat, a few words of Hindoostanee, and in Calcutta it was not really the thing to be seen speaking the local lingo too well. The only man I knew who had actually learnt any was sitting next to me, and Frank Macpherson had no desire to fight or command troops. He had just effected a transfer to the Political Department and his ambition was to become a magistrate or some such, running a station somewhere up country. He had already passed his diploma in Hindoostanee and was now studying Persian. He had been managing his company’s accounts and administering to his

sepoys

’ welfare since shortly after he had arrived. Now I envied his activity. Idleness left me enervated, lethargic and irritable.

‘I hate these damned litters, they make me ill,’ I grumbled.

‘Whereas I love them. I shall say it once more, now I am in the Political Department I shall travel India in a sedan chair and never sit on a horse again.’ Frank looked me over. ‘Oh, William, for heaven’s sake, would you rather be going to Blacktown on an errand for Government House that at the very least will keep you occupied for an afternoon? Or would you rather be dead?’

‘You know, Frank,’ I said, rubbing my temples hard to dispel the ache, ‘there are times when I think I would rather be dead.’

‘You should be ashamed to say anything so stupid,’ he said, severely. ‘You should be careful of what you wish for.’

‘I am sorry, Frank, forgive me,’ I said, instantly remorseful. ‘I am good for nothing in this state.’

I set my jaw against the throb in my temples, and smiled as much as I could manage. The truth was death came with alarming and casual ease in Calcutta. We had seen our fellow cadets taken overnight by the cholera, or a sudden fever, or some horrible unforeseen

accident. One had died when a bullock cart loaded with sharpened wooden staves had collided with his horse. September was a bad month for fevers and diseases in Calcutta. The chaplain of Frank’s regiment said that though the month was but half over, he had already seen thirty burials.

‘Why they are sending me to deliver this thing I do not know.’

Frank raised an eyebrow. ‘You said you were bored.’

‘You!’

‘I simply mentioned that my able and presentable friend was at a loose end.’

He thrust a water bottle into my hands. I made a face, but drank. I had assumed I had been chosen to go to Blacktown because I was the least occupied, least sickly junior officer to hand. It had never occurred to me that Frank might have had a hand in it.

‘Besides, I wanted to have a look at Blacktown,’ he went on, ‘and I could not very well volunteer myself. And are you not curious to know who this Jeremiah Blake is?’

‘Some tragic, leprous, broken-down old creature gone native, too opium-addled to collect his own pension,’ I said heavily.

‘Mebbe,’ said Frank. ‘Ah! The scent of the

ghats

is pungent today.’

The palanquin drew up to the Hooghly River ghats. These are the large steps that descend to the water and pass as quays in India. The river was like Calcutta itself. From a distance, it seemed picturesque, the gilt-covered barges of the rich natives and the bumboats selling fruit and fish, and the glimpses of the graceful mansions of Garden Reach on the other side. But close to, it was a different story. The ghats were always chaotic, crowded and dirty, and the stink of stale fish lay over them like a fog. Beggars in tiny boats waved their stumps for coins, and the native food-sellers were aggressively accosting or sullenly inscrutable. Worst of all were the half-burnt corpses that floated through the murky water. The Hindoos brought their dead down to the ghats to burn them, but they rarely spent enough on fuel to do more than burn the skin off before tipping them into the water. Once the funeral rituals were performed, no further attention was paid to these hideous objects, as if they no longer existed. Native men and women

washed themselves and even filled pigskin water bottles – the creatures returning to their former animal forms as the water re-inflated them.

‘You know,’ I said, ‘I often think that if one wished to commit a murder in Calcutta, a perfect way of disposing of the body would be to partially burn it and tip it into the Hooghly. Everyone would ignore it.’

‘What a ghoulish thought, though it would make a splendid story,’ said Frank.

Frank was my personal compensation for Calcutta. I thanked God for him every day. We had arrived in Calcutta at the same time and moved out of the grim cadets’ quarters at Fort William as soon as possible to mess together. The rowdier among our messmates regarded him as the most tremendous spoon: he drank barely a drop; he did not shoot or gamble or ride, all of which I did excessively. Nor did he visit

nautches

or keep a

bibi

– a native mistress. He cared nothing for what anyone thought and he was always good-humoured, a quality I had thought I possessed until I had arrived in India. While Calcutta conspicuously exposed my own weaknesses, it brought out the best in Frank. His conscientiousness was a daily reproof to my impatience, my sore head, my occasional indulgences in the fleshpots of Calcutta, and my nightly gambling losses. (I was, like most ensigns, horribly in debt.) Despite this, I liked him enormously.

We turned into an unfamiliar street of small open cupboards that passed for shops, selling clay figures painted into the gaudy likenesses of the Hindoo gods: Shiva, Durga and the hideous Kalee, patron goddess of Calcutta, her red tongue lolling out of her grotesque black face, a necklace of heads round her neck.

‘The potters’ neighbourhood,’ Frank said, happily.

Truth be told, I had arrived in Calcutta expecting to be as seduced by its ancient traditions and exotic scenes as Frank still was. At first the lush vegetation, the sight of a camel or elephant, had been an excitement. But as time passed the notions I had harboured about the beauty of the place, and my hopes of distinguishing myself, had been replaced by an intense and bitter homesickness for England

and the realization that it was more than likely I would never see it again. The odds – well understood but never spoken aloud – were that most of us would die before ever we returned.

The one enduring romance I still found in India was in the glorious prose of Xavier Mountstuart. I had discovered Mountstuart as a boy in Devon, where I had attended a small school for the sons of the local gentry kept by the local vicar. One of his assistants had lent me a copy of

Knight Rupert

. I had been thrilled by it. My family were not readers, but Xavier Mountstuart’s writings had inspired and transported me. I had devoured

The Courage of the Bruce

and

The Black Prince

, then graduated to the Indian writings:

The Lion of the Punjab

, of course, and the tales of bandits and rebels in the

Foothills of Nepal

. I had read of white forts and marble palaces and maharajas’ emeralds; of zenanas and nautch girls in the

Deccan

; of the sieges and jangals. I had even read a short tract about Hindooism, vegetarianism and republicanism, which had left me a little confused. Mountstuart seemed to me the very acme of Byronic manhood. It was not simply that he was a poet and writer of genius, but that he had lived his writings. He was the reason I had come to India – something I had not, of course, confided to my father. He had approved of my going to India because, having bought a commission in His Majesty’s army for my oldest brother and set up another (now dead) in the professions, there was no money left to do anything for me. In the East India Company’s armies, positions were not sold but contacts counted for something, and since the family had a few Company connections, I had been sent off, cradling my precious volumes of Mountstuart’s works.

Recently I had scraped together the wherewithal to purchase a brand-new copy of the first volume of

Leda and Rama

. This was causing a most tremendous furore in Calcutta for, under the guise of being a stirring, even immodest, romance about forbidden love and warfare between rival Indian kingdoms, it was a thinly veiled account of adulterous entanglements and corruption among some of Calcutta’s most elevated worthies. People talked of nothing else. Mountstuart was no longer

persona grata

in the city’s drawing-rooms, but Society – from the most respectable elderly matrons to

the most junior clerks – all wanted to read his book. Nothing so exciting had happened in an age.

The bearers took a series of turns down muddy lanes barely wide enough for the palanquin until we arrived on a wide thoroughfare next to a noisy chaotic bazaar. A large cow stood moodily in the middle of the road like a rock in a fast-flowing stream forcing the waters to part around it. Around us a column of natives carried whole dead animals on long bamboo poles. Even inside the litter I could feel the crush and smell of bodies.

‘William! See the fakir!’ Frank cried, delighted. The creature was sitting by the roadside, smeared in ash, wearing only a long white stringy beard that dangled past his stomach. But it was his hands that drew the eye. They were hideous: the fingernails had grown through the flesh of the hands and emerged through the knuckles, long and horribly twisted. Where I felt repulsion, however, Frank experienced only cheerful curiosity and an enjoyable shudder of wonder. Though I was a better messmate, a better shot, and blessed with stupid good health, I was gradually coming to accept that Frank – short, pale and prone to chills – might be better suited to India than I.

The palanquin came to an abrupt stop and began to shake alarmingly as if the bearers were trying to roll us out. We had come to stop at the corner, or what passed for a corner, of an even narrower lane.

‘

Bas you budzats!

’ Enough, you blackguards, I shouted.

Awkwardly we climbed out, one after the other. A wave of hot smells assailed me: sweat, over-ripe fruit, heavy and sweet, and beneath, other ranker scents I did not care to identify. The road was soft and oozing, mud already specked my white breeches, native bodies surged and shoved, entirely too close. We were the only white faces. The

harkara

who had been running alongside the palanquin bowed and pointed down the narrow muddy lane. I spoke loudly and slowly: ‘Up here?’ Then, even louder, ‘English-wallah live here?’