The Success and Failure of Picasso (25 page)

Read The Success and Failure of Picasso Online

Authors: John Berger

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Artists; Architects; Photographers

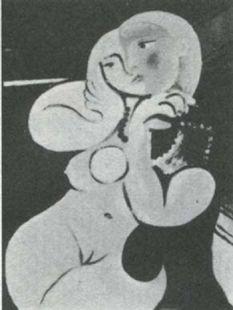

All that we have noticed about inconsistencies in the

Nude Dressing her Hair

applies equally to

First Steps.

Again this painting does no more than confront us with the evidence of Picasso’s apparent wilfulness. But this time with far less reason, for the emotional charge is much smaller. It is not now a

cri de cœur

which tragically fails to achieve art, but mannerism.

84

Picasso. First Steps. 1943

The experience is Picasso’s experience of his own way of painting. It is like an actor being fascinated by the sound of his own voice or the look of his own actions. Self-consciousness is necessary for all artists, but this is the vanity of self-consciousness. It is a form of narcissism: it is the beginning of Picasso impersonating himself. When we look at the

Nude Dressing her Hair

we are at least made to feel shock. Here we only become aware of the way in which the picture is painted – and this can be called clever or perverse according to taste.

It would be petty to draw attention to such a failure if it was incidental. What artist has not sometimes been vain or self-indulgent? But later, after 1945, a great deal of Picasso’s work became mannered. And at the root-cause of this mannerism there is still the same problem: the lack of subjects – so that the artist’s own art becomes his subject.

85

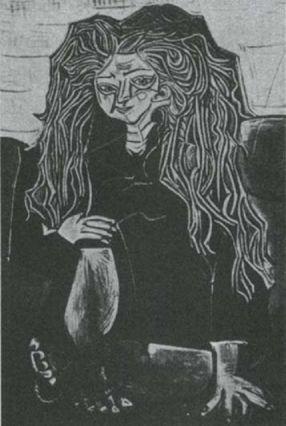

Picasso. Portrait of Mrs H. P. 1952

The

Portrait of Mrs H. P.

is a typical later example. The style is different, but not the degree of mannerism. So much is happening in terms of painting – the hair like a maelstrom, the legs and the hand painted fast and furiously, the face with its strange, abrupt hieroglyphs of expression – but what does it all add up to? What does it tell us about the sitter except that she has long hair? What is all the drama about? Unhappily, it is about

being painted by Picasso.

And that is the extremity of mannerism, the extremity of a genius who has nothing to which to apply himself.

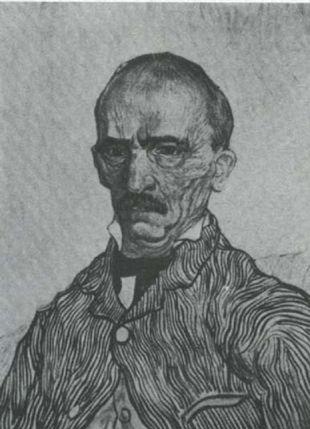

To show how much a dramatically painted portrait can say, let me quote, without comment, a portrait by Van Gogh.

86

Van Gogh. Portrait of the Chief Superintendent of the Asylum at Saint-Remy. 1889

On the evidence of seven paintings I have tried to show you how, from about 1920 onwards, Picasso has sometimes failed to find subjects with which to express himself, and how, when this happens, he virtually destroys the nominal subject he has taken, and so makes the whole painting absurd. There are other paintings in which this has happened. There are even more in which it has partially happened. There are also paintings in which he has found his subject.

It would be as stupid to deny the originality of Picasso’s failures as to pretend that this originality transforms them into masterpieces. Picasso is unique but, since he is a man and not a god, it is our responsibility to judge the value of this uniqueness.

It is not my intention to draw up a definitive list of Picasso’s failures as opposed to his masterpieces. What I hope I have shown is the relevance of asking a particular question about Picasso. The question, I believe, leads to a standard by which all his work can usefully be judged.

Apart from the Cubist years, nearly all Picasso’s most successful paintings belong to the period from 1931 to 1942 or 43. During this decade he at one moment – in 1935 – gave up painting altogether. It was a time of great inner stress. But it was also the period when he most successfully found his subjects. These subjects were related to two profound personal experiences: a passionate love affair, and the triumph of

fascism first in Spain and then in Europe.

In the countless books about Picasso no secret is ever made of his many love affairs; indeed they have become part of the legend. Only one affair is passed over quickly – and that is the one to which I now refer. It is typical of the lack of realism which surrounds Picasso’s reputation that this should be the case. There is no need to pry into his private life – even though this is so often and tastelessly described by his friends; but one fact has to be noted, because it is so directly related to his art. On the evidence of his paintings, his sculpture, and hundreds of drawings in sketchbooks, the sexually most important affair of his life was with

Marie-Thérèse Walter whom he first met in 1931. He has painted and drawn no other woman in the same way, and no other woman half as many times. It may be that she became a kind of symbol for him, and that in time the idea of her meant more to him than she herself. It may be that in the full sense of the word he was more devoted to other women. I do not know. But there is not the slightest doubt that for eight years he was haunted by her – if one can use a word normally applied to spirits to refer to somebody whose body was so alive for him.

87

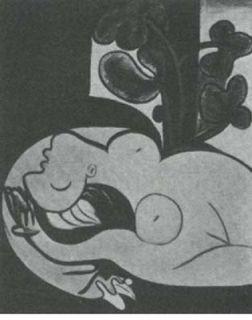

Picasso. Nude on a Black Couch. 1932

88

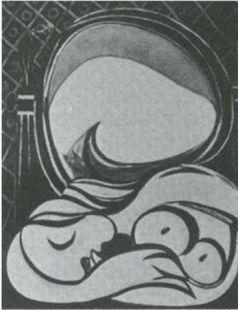

Picasso. The Mirror. 1932

89

Picasso. Woman in a Red Armchair. 1932

Today, among the five hundred or more of his own past paintings which Picasso owns, over fifty are of Marie-Thérèse. No other person dominates his collection a quarter as much. When he paints her, her subject is always able to withstand the pressure of his way of painting. This is because he is single-minded about her, and can see her as the most direct manifestation of his own feelings. He paints her like a Venus, but a Venus such as nobody else has ever painted.

What makes these paintings different is the degree of their direct sexuality. They refer without any ambiguity at all to the experience of making love to this woman. They describe sensations and, above all, the sensation of sexual comfort. Even when she is dressed or with her daughter (the daughter of Marie-Thérèse and Picasso was born in 1935) she is seen in the same way: soft as a cloud, easy, full of precise pleasures, and inexhaustible because alive and sentient. In literature the thrall which a particular woman’s body can have over a man has been described often. But words are abstract and can hide as much as they state. A visual image can reveal far more naturally the sweet mechanism of sex. One need only think of a drawing of a

breast and then compare it to all the stray associations of the word, to see how this is so. At its most fundamental there aren’t any words for sex – only noises: yet there are shapes.

The old masters recognized this advantage of the visual. Most paintings have a far greater sexual content than is generally admitted. But when the subjects have been undisguisedly sexual, they have always in the past been placed in a social or moral perspective. All the great nudes imply a way of living. They are invitations to a particular philosophic view. They are comments on marriage, having mistresses, luxury, the golden age, or the joys of seduction. This is as true of a Giorgione as of a Renoir. The women lie there like conditional promises. The subjective experience of sex – the experience of the fulfilling of the promise – is ignored. (And ignored most pointedly of all in ‘pornographic’ pictures illustrating the sexual act.)

It is understandable that this should have been so in the past. There were stricter religious and social taboos. There was greater economic dependence of women and therefore a greater emphasis on the conventions of chastity and modesty. There was an established public role of art. A painting was painted for somebody else, so that ‘autobiographical’ painting was very rare; the subjective experience of sex can only be expressed autobiographically. There were also stylistic limitations.

The painter’s right to displace the parts – the right which Cubism won – is essential for creating a visual image that can correspond to sexual experience. Whatever the initial stimuli of appearances, sex itself defies them. It is both brighter and heavier than appearances, and finally it abandons both scale and identity.