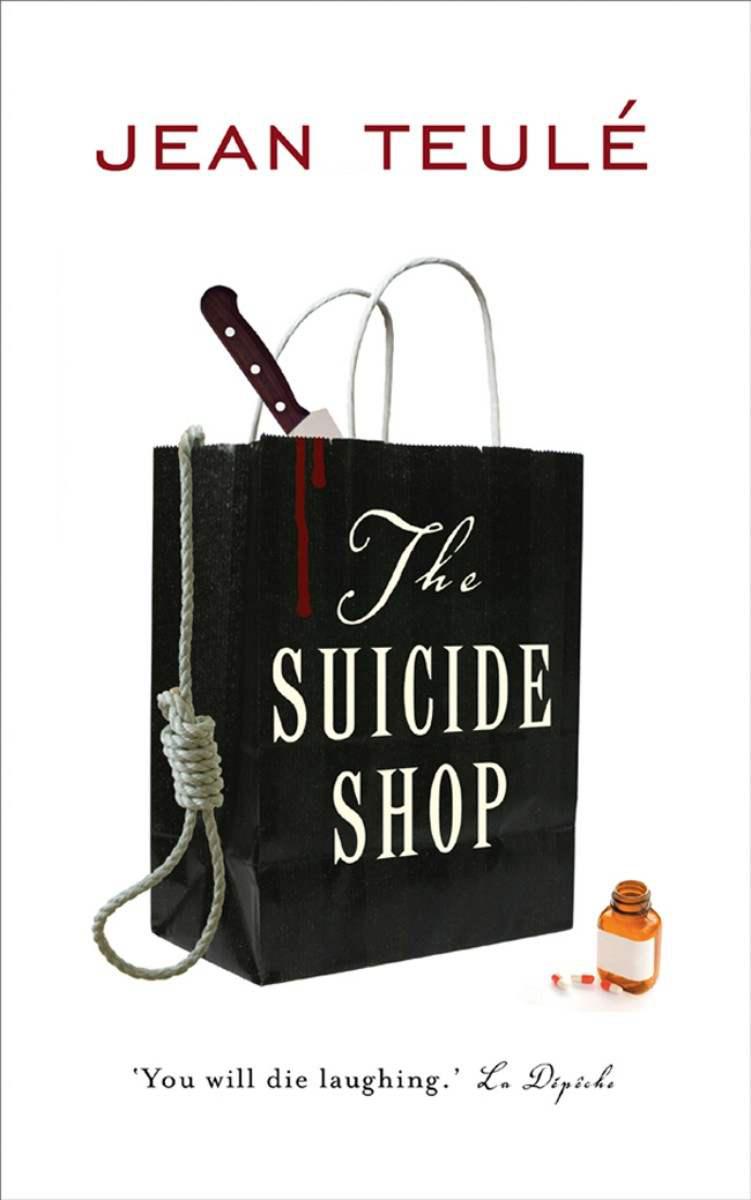

The Suicide Shop

Authors: Jean TEULE

SHOP

JEAN TEULÉ

Translated by Sue Dyson

Title Page

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

THE SUICIDE SHOP

Copyright

1

No sunshine ever penetrates this small shop. The only window, to the left of the front door, is obscured by paper cones and piles of cardboard boxes, and a writing slate hangs from the window catch.

Light from the neon strips on the ceiling falls on an old lady who goes up to a baby in a grey perambulator.

‘Aah, he’s smiling!’

The shopkeeper, a younger woman sitting by the window facing the cash register, where she’s doing her accounts, objects. ‘My son smiling? No, he’s not. He’s just making faces. Why on earth would he smile?’

Then she goes back to her adding up while the elderly customer walks round the hooded pram. Her walking stick and fumbling steps give her an awkward appearance. Although her deathly eyes, dark and doleful, are veiled with cataracts she is sure of what she is seeing:

‘But he does look as if he’s smiling.’

‘Well, I’d be amazed if he were; nobody in the Tuvache family has ever smiled!’ counters the mother of the newborn baby, leaning over the counter to check.

She raises her head and, craning her bird-like neck, calls out: ‘Mishima! Come and look at this!’

A trapdoor in the floor opens like a mouth and, tongue-like, a bald pate pops out.

‘What? What’s going on?’

Mishima Tuvache emerges from the cellar carrying a sack of cement, which he sets down on the tiled floor while his wife says: ‘This customer claims Alan is smiling.’

‘What are you talking about, Lucrèce?’

Dusting a little cement powder from his sleeves, he too goes up to the baby, and gives him a long, doubtful look before offering his diagnosis:

‘He must have wind. It makes them pull faces like that,’ he explains, waving his hands about in front of his face. ‘Sometimes people confuse it with smiling, but it’s not. It’s just pulling faces.’

Then he slips his fingers under the pram’s hood and demonstrates to the old woman: ‘Look. If I push the corners of his mouth towards his chin, he’s not smiling. He looks just as miserable as his brother and sister have looked from the moment they were born.’

The customer says: ‘Let go.’

The shopkeeper lets go of his son’s mouth. The customer exclaims: ‘There! You see, he

is

smiling!’

Mishima Tuvache stands up, sticks out his chest and demands irritably: ‘So what was it you wanted, anyway?’

‘A rope to hang myself with.’

‘Right. Do you have high ceilings at home? You don’t know? Here,’ he continues, taking down a length of hemp from a shelf, ‘take this. Two metres should be enough. It comes with a ready-tied slip-knot. All you have to do is slide your head into the noose …’

As she is paying, the woman turns towards the pram. ‘It does a heart good to see a child smile.’

‘Whatever you say!’ Mishima is annoyed. ‘Go on, go home. You’ve got things to be getting on with there now.’

The desperate old lady goes off with the rope coiled round one shoulder, under a lowering sky. The shopkeeper goes back into the shop.

‘Phew. Good riddance! She’s a pain in the neck, that woman. He’s not smiling.’

Madame Tuvache is still standing near the cash register; she can’t take her eyes off the child’s pram, which is shaking all by itself. The squeaking of the springs mingles with the gurgles and peals of laughter coming from inside the baby carriage. Stock-still, the parents look at each other in horror.

‘Shit …’

2

‘Alan! How many more times do I have to tell you? We do not say “see you soon” to customers when they leave our shop. We say “goodbye”, because they won’t be coming back, ever. When will you get that into your thick head?’

A furious Lucrèce Tuvache stands in the shop, a sheet of paper concealed behind her back in her clenched hand. It quivers to the rhythm of her anger. Her youngest child is standing in front of her in shorts, gazing up at her in his cheerful, friendly way. Stooping, she reprimands him sternly, taking him to task. ‘And, what’s more, you can stop chirping’ – she imitates him – ‘“Goo-ood morn-ing!” when people come in. You must say to them in a funereal voice: “Terrible day, Madame,” or: “May you find a better world, Monsieur.” And please PLEASE stop smiling! Do you want to drive away all our customers? Why do you have this mania for greeting people by rolling your eyes round and wiggling your fingers on either side of your ears? Do you think customers come here to see your smile? It’s getting on my nerves. We’ll have to get you fitted with a muzzle, or have you operated on!’

Madame Tuvache, five foot four, and in her late forties, is hopping mad. She wears her brown hair fairly short and tucked behind her ears, but the lock on her brow gives her hairstyle a touch of life. As for Alan’s blond curls, when his mother shouts at him they seem to take off, as though blown by a fan.

Madame Tuvache brings out the sheet of paper she’s been hiding behind her back. ‘And what’s this drawing you’ve brought home from nursery school?’

With one hand she holds the drawing out in front of her, tapping it furiously with the index finger of her other hand.

‘A path leading to a house with a door and open windows, under a blue sky where a big sun shines! Now come on, why aren’t there any clouds or pollution in your landscape? Where are the migratory birds that shit Asian viruses on our heads? Where is the radiation? And the terrorist explosions? It’s totally unrealistic. You should come and see what Vincent and Marilyn were drawing at your age!’

Lucrèce bustles past the end of a display unit, where a large number of gleaming golden phials are on display. She passes in front of her elder son, a skinny fifteen-year-old, who is biting his nails and chewing his lips, his head swathed in bandages. Next to him, Marilyn, who’s twelve and overweight, is slumped in a listless heap on a stool – with one yawn she could swallow the world – while Mishima pulls down the metal shutter and begins switching off some of the neon lights. Madame Tuvache opens a drawer beneath the cash register and takes out an order book. Inside it are two sheets of paper, which she unfolds.

‘Look how gloomy this drawing of Marilyn’s is, and this one of Vincent’s: bars in front of a brick wall! Now that I like.

There’s

a boy who’s grasped something about life! He may be a poor anorexic who suffers so many migraines that he thinks his skull’s going to explode without the bandages … but he’s the artist of the family, our Van Gogh!’

She continues, still lauding Vincent as a worthy example: ‘He’s got suicide in his blood. A real Tuvache, whereas you, Alan …’

Vincent comes over, with his thumb in his mouth, and snuggles up to his mother. ‘I wish I could go back inside your tummy …’

‘I know …’ she replies, caressing his crêpe bandages and continuing to examine little Alan’s drawing: ‘Who’s this long-legged girl you’ve drawn, bustling about next to the house?’

‘That’th Marilyn,’ replies the six-year-old child.

At this, the Tuvache girl with the drooping shoulders limply raises her head, her face and red nose almost entirely hidden by her hair, while her mother exclaims in surprise: ‘Why have you drawn her so busy and pretty, when you know very well she always says she’s useless and ugly?’

‘I think she’th beautiful.’

Marilyn claps her hands to her ears, leaps off the stool and runs to the back of the shop screaming as she climbs the stairs leading to the apartment.

‘There, now he’s made his sister cry!’ yells Marilyn’s mother, while her father switches off the last of the shop’s neon lights.

3

‘When she had mourned Antony’s death in this way, the queen of Egypt crowned herself with flowers and then commanded her servants to prepare a bath for her …’

Madame Tuvache is sitting on her daughter’s bed, telling Marilyn the story of Cleopatra’s suicide to help her get to sleep.

‘After her bath, Cleopatra sat down to eat a sumptuous meal. Then a man arrived from the countryside, carrying a basket for her. When the guards asked him what it contained, he opened it, parted the leaves and showed them that it was full of figs. The guards marvelled at the size and beauty of the fruit, so the man smiled and invited them to take some. Thus reassured, they allowed him to enter with his basket.’

Red-eyed, Marilyn lies on her back and gazes at the ceiling as she listens to her mother’s beautiful voice, which continues: ‘After her lunch, Cleopatra wrote on a tablet, sealed it and had it sent to Octavius; then she dismissed everyone except one serving-maid, and closed the door.’

Marilyn’s eyes begin to close and her breathing becomes more even …

‘When Octavius broke the seal on the tablet and read Cleopatra’s pleas to be buried alongside Antony, he immediately realised what she had done. First he considered going to save her himself, then hurriedly sent some men to find out what had happened … Events must have moved quickly, because when they rushed in they caught the guards unawares: they hadn’t noticed anything. When they opened the door they found Cleopatra lying dead on a golden bed, dressed in her royal robes. Her servant, Charmian, was arranging the diadem on the queen’s head. One of the men said to her angrily: “Beautifully done, Charmian!”

‘“It is well done,” she replied, “and fitting for a princess descended of so many royal kings.” As Cleopatra had ordered, the asp that had arrived with the figs had been hidden underneath the fruit, so that the snake could attack her without her knowing. But when she removed the figs she saw it and said: “So there it is,” and bared her arm, offering it up to be bitten.’

Marilyn opened her eyes, as though hypnotised. Her mother stroked her hair while she finished her story.

‘Two small, almost invisible pinpricks were found on Cleopatra’s arm. Although Octavius was grief-stricken at her death, he admired her noble spirit and had her buried next to Antony with royal pomp and splendour.’

‘If

I’

d been there, I’d have made the thnake into pretty thlippers tho Marilyn could go and danth at the Kurt Cobain dithco!’ said Alan. The door to his sister’s bedroom was half open, and he was standing in the doorway.

Lucrèce swung round brusquely and glowered at her youngest child. ‘You – back to bed! Nobody asked your opinion.’

Then, as she stood up, she promised her daughter: ‘Tomorrow night I’ll tell you how Sappho threw herself off a cliff into the sea and all for a young shepherd’s beautiful eyes …’

‘Mother,’ sniffed Marilyn, ‘when I’m grown up, can I go and dance with boys at the disco?’

‘No, of course not. Don’t listen to your little brother. He’s talking nonsense. You always say you’re a lump – do you really think men would want to dance with you? Come on, settle down for some nightmares. That’s more sensible.’

Lucrèce Tuvache, her beautiful face grave, is just joining her husband in their bedroom when the emergency bell rings down below.

‘Well, we are on duty at night …’ sighs Mishima. ‘I’ll go.’

He goes downstairs in the dark, grumbling: ‘Damn, I can’t see a thing. One false step and I could break my neck!’

From the top of the stairs, Alan’s voice suggests: ‘Daddy, inthtead of moaning about the dark, why not turn on the light?’

‘Yes, thank you, Mr Know-it-all. When I want your advice …’

Nevertheless the father does as his son suggests and, by the glow of the crackling electric bulb on the staircase, he goes into the shop, where he switches on a row of neon lights.

When he comes back upstairs, his wife is propped up with a pillow, a magazine in her hands. ‘Who was it?’ she asks.

‘Dunno. Some desperate bloke with an empty revolver. I found what he needed in the ammunition boxes by the window so that he could blow his brains out. What are you reading?’

‘Last year’s statistics: one suicide every forty minutes, a hundred and fifty thousand attempts, only twelve thousand deaths. That’s incredible.’

‘Yes, it is incredible. The number of people who try to top themselves and bungle it … Fortunately

we’re

here. Turn off the light, darling.’

From the other side of the wall, Alan’s voice rings out: ‘Thweet dreamth, Mummy. Thweet dreamth, Daddy.’

His parents sigh.