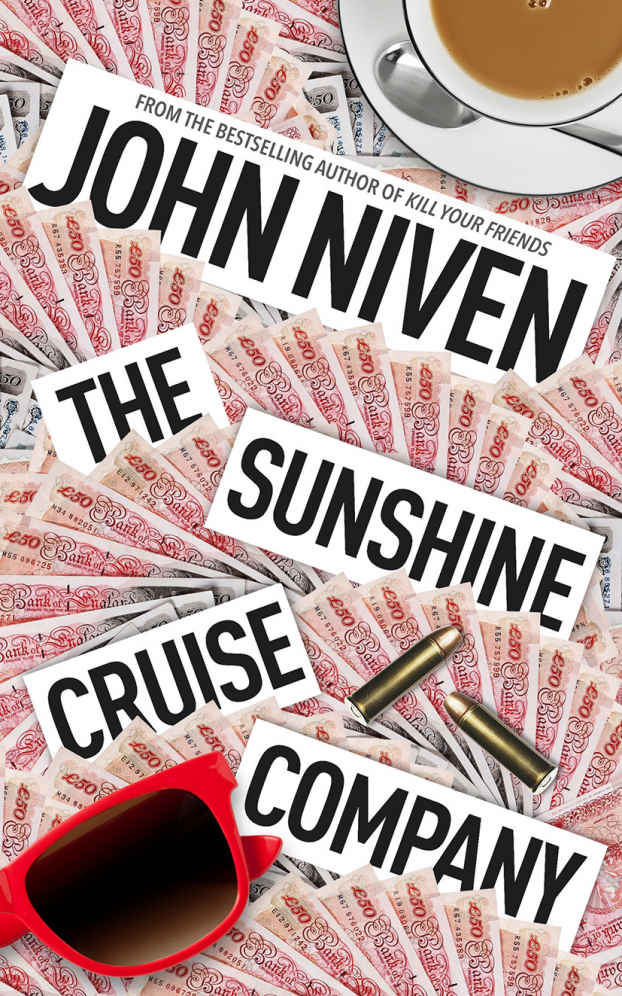

The Sunshine Cruise Company

Read The Sunshine Cruise Company Online

Authors: John Niven

Contents

Susan Frobisher and Julie Wickham are turning sixty. They live in a small Dorset town and have been friends since school. On the surface Susan has it all – a lovely house and a long marriage to accountant Barry. Life has not been so kind to Julie, but now, with several failed businesses and bad relationships behind her, she has found stability: living in a council flat and working in an old people’s home.

Then Susan’s world is ripped apart when Barry is found dead in a secret flat – or rather, a sex dungeon. It turns out Barry has been leading a double life as a swinger. He’s run up a fortune in debts and now the bank is going to take Susan’s home.

Until, under the influence of an octogenarian gangster named Nails, the women decide that, rather than let the bank take everything Susan has, they’re going to take the bank. With the help of Nails and the thrill-crazy, wheelchair-bound Ethel they pull off the daring robbery, but soon find that getting away with it is not so easy.

The Sunshine Cruise Company

is a sharp satire on friendship, ageing, the English middle classes and the housing bubble from one of Britain’s sharpest and funniest writers.

John Niven was born in Irvine, Ayrshire. He is the author of the novella

Music from Big Pink

and the novels

Kill Your Friends

,

The Amateurs

,

The Second Coming

,

Cold Hands

and

Straight White Male

.

Music from Big Pink

Kill Your Friends

The Amateurs

The Second Coming

Cold Hands

Straight White Male

Cruise Company

John Niven

To Sheila Sheerin

SO MUCH BLOOD,

Susan Frobisher thought.

So much blood.

She was at the kitchen counter, absolutely covered in the stuff. It was spattered all over the worktops, her apron and her face. A huge bowlful of it stood in front of her. The horror-show aspect of the scene was hugely magnified by her kitchen’s whiteness. Traditional Shaker. They’d only had it done last year. All the gadgets: sliding chiller drawer at knee height, waste-disposal unit, one of those bendy taps like you saw on the cooking shows and even a built-in wine cooler. Not that she and Barry drank very much these days, but still, it looked nice, all those frosted bottles lined up like missiles in the bomb bay. (Emperor Kitchens on the Havering Road had done it. Barry had negotiated a very good deal, as always. He loved doing it. Negotiating.) Susan checked her reflection in the smoked-glass door of the cooler and, blood aside, was pleased with what she found as she approached her sixtieth year: her complexion was still youthful, her eyes clear and her figure trim. Her hair had been grey for nearly a decade now, however, and Julie was always on at her to have it done, although the days when it would have been Julie’s ‘treat’ were now long past …

Outside, through the double glazing, the dew was already lifting from the half of the garden the sun was hitting. The first week of May and, finally, spring had properly arrived down here in Dorset. Susan stuck her pinkie into the bowl of blood and put it in her mouth. Mmmm. Not quite sure about the texture. It had to be just right.

If you get it just right, as her great hero the special-effects wizard Tom Savini said, ‘You can create illusions of reality – make people think they’ve seen things they really haven’t seen.’ Horror movies were Susan’s private little vice. (Barry couldn’t stand them, couldn’t stand movies of any kind in fact. ‘Load of rubbish,’ he’d sneer. ‘Somebody just made it all up!’ He liked documentaries. War stuff.) She’d seen everything Savini had ever done –

Friday the 13th

,

The Burning

,

Dawn of the Dead

. She’d watch them curled up with her tea when Barry was working late.

As if on cue Barry Frobisher walked into the kitchen, knotting his tie. He surveyed the scene and said: ‘What the bloody hell …’

‘Not quite the right consistency,’ Susan said. ‘Too thin.’

‘Look at the mess!’

‘I’ve got to get it done now. I’ve the shopping to do and then Julie’s birthday lunch this afternoon, then dress rehearsals tonight.’

‘Christ. Can’t you just … buy this bloody stuff, Susan?’

‘No budget, darling.’

Barry sighed as he moved towards the coffee pot, his partially tied tie still loose around his neck, picking up a cup from the kitchen table as he went. (They always laid the kitchen table for breakfast the night before, before they went to bed.) ‘I don’t know what you get out of this, Susan, I really don’t.’

He took a slice of cold toast from the rack and started buttering it thickly. He’d have been better off with some cereal, Susan thought, that waistline of his, really starting to crawl over the band of his trousers. A 42-inch waist she’d had to buy him, the last time they went clothes shopping in M&S. Not to mention what it was probably doing to his arteries. Susan heard him wheezing a bit in the mornings these days, just with the effort of levering himself out of bed. (

His

bed. They’d finally gone down that road a few years back: his and hers single beds on either side of the room. They both liked different mattresses anyway. Better to get a good night’s sleep. And, as Barry pointed out, his back was bad and it’s not like they were newly-weds. That side of things happened only very occasionally these days. In fact, when was the last time? Susan strained to remember. Around Christmas? Maybe before.)

‘It’s fun,’ Susan said, answering his question.

Barry snorted.

Wroxham Players – Susan’s ‘creative outlet’.

She was no actor. (Not that many of them were.) She’d started out helping with wardrobe and had now been in charge of Costumes and Props for the past three years. Jesus, Barry thought, the first nights he’d been obliged to attend. Bunch of pensioners and starry-eyed teenagers stepping into the scenery and over each other’s lines. Still, it was harmless enough, he supposed. Kept her off the streets and all that. He poured himself some coffee while, in the background, Susan added more corn syrup to the fake-blood mixture. ‘What is it this year?’ Barry asked over his shoulder.

‘

King Lear

.’

He thought for a moment. ‘That’s … Shakespeare?’

‘Yes,’ Susan said. Not a reader, her Barry. A good provider. An accountant. A

chartered

accountant, Susan used to hear herself saying proudly.

‘What’s it about then? That one,’ he asked, sipping his black coffee.

‘Oh, the indignity of old age you could say,’ Susan said, stirring the mixture, wondering if there would be enough of it. She feared Frank, the director, was intending to go a little Peckinpah in the eye-gouging scene. She wondered if the sensibilities of the average Wroxham audience could take it.

‘Sounds cheery,’ Barry said, opening the

Daily Mail

over at the table, already only half listening.

Look at this – bloody East Europeans. All over the place.

Old age.

They’d both be sixty this year. Their thirty-fifth wedding anniversary. What was that? Susan wondered. Jade? Topaz or something? And was it really ten years since their silver wedding? Such a lovely little party Tom and Clare had thrown for them, in the function suite down at the Watermill. Not that they saw much of Tom and Clare. Both caught up with their careers. At that age now, early 30s. Still, Susan did find it odd that their son and his wife had been together over a decade now and still hadn’t produced a grandchild. It seemed to be the way these days. She’d been nearly thirty when she had Tom, back in 1983. They’d classified her as an ‘old mum’. Special attention. Nowadays thirty seemed young to be having children. What was Clare now? Thirty-two? Thirty-three? Anyway – they wanted to be getting a move on in Susan’s view.

She gave the water/corn syrup/ketchup mixture a final stir, pleased with the consistency now, and started looking in the drawer beneath the sink for the plastic ziplock freezer bags.

How best to ask him?

Susan was wondering.

Tricky ground. Julie and Barry had never enjoyed good terms. Julie, Susan suspected, thought Barry was boring. Barry, she very much knew, thought Julie was completely mental. A bad influence. True, Julie had always been wilder than Susan,

way

wilder back in the day, but she wasn’t crazy. Still, she’d had a hell of a life, Julie. Maybe play to Barry’s sense of superiority. ‘Oh, darling?’

‘Mmm?’

Eight hundred quid a week in benefits? Shiftless bastards.

‘Could you put an extra three hundred into my account please?’

‘Eh? What for?’

‘Well, I spent a little more than I meant to on Julie’s birthday present.’

‘For Christ’s sake, Susan –’

‘It’s her sixtieth, Barry! And she’s had a terrible time of it these last few years. Losing her business. That bugger running off with all her money. That flat she’s in. That awful job. I wanted to get her something nice.’