The Tao of Natural Breathing (15 page)

Read The Tao of Natural Breathing Online

Authors: Dennis Lewis

PSYCHOLOGICAL OBSTACLES TO AUTHENTIC BREATHING

Once we begin to get in touch with the sensation of this structure, however, we will begin to become aware of the mental and emotional forces acting on our breath, on our own particular rhythms of inhalation and exhalation. This is a crucial aspect of any serious work with breathing, since it will show us the psychological obstacles to discovering our own authentic breath.

Our Inability to Exhale Fully

According to Magda Proskauer, a psychiatrist and pioneer in breath therapy, one of the main obstacles “to discovering one’s genuine breathing pattern” is the inability that many of us have to exhale fully. Whereas inhalation requires a certain amount of tension, exhalation requires letting go of this tension. Full inhalation without full exhalation is impossible. It is important, therefore, to see what stands in the way of full exhalation. For many of us, what stands in the way is often what is no longer necessary in our lives. Proskauer points out that “Our incapacity to exhale naturally seems to parallel the psychological condition in which we are often filled with old concepts and long-since-consumed ideas, which, just like the air in our lungs, are stale and no longer of any use.”

43

,

44

She makes it clear that in order to exhale fully we need to learn how to let go “of our burdens, of our cross which we carry on our shoulders.” By letting go of this unnecessary weight, we allow our shoulders and ribs to relax, to sink downward into their natural position instead of tensing upward. Full exhalation follows quite naturally.

Our Inability to Inhale Fully

Those of us who are unable to exhale fully in the normal circumstances of our lives are obviously unable to inhale fully as well. In full inhalation, which originates in the lower breathing space and moves gradually upward through the other spaces, one’s abdomen, lower back, and rib cage must all expand. This, as we have seen in earlier chapters, helps the diaphragm, which is attached all around the bottom of the rib cage and anchored to the spine in the lumbar area, to achieve its full range of movement downward. For this to happen, the muscles and organs involved in breathing must be in a state of dynamic harmony, free from unnecessary tension. But this expansion is not just a physical phenomenon, it is also a psychological one. It depends on both the wish and the ability to engage fully with our lives, to take in new impressions of ourselves and the world.

Freedom To Embrace the Unknown

Full exhalation and inhalation are thus most possible when we are free enough to let go of the known and embrace the unknown. In full exhalation, we empty ourselves—not just of carbon dioxide, but also of old tensions, concepts, and feelings. In full inhalation, we renew ourselves—not just with new oxygen, but also with new impressions of everything in and around us. Both movements of our breath depend on the “unoccupied, empty space” that lies at the center of our being. It is the sensation of this inner space (and silence)—which we can sometimes experience in the natural pause between exhalation and inhalation—that is our path into the unknown. It is the sensation of this space that can enliven us and make us whole.

PRACTICE

To prepare for this practice, sit or stand quietly with your eyes open and experience the coming and going of your breath. Get in touch with the three tan tiens—just below the navel, in the solar plexus, and between the eyebrows. Sense the different qualities of vibration in these areas. As you breathe, sense your outer and inner breath—the various upward and downward movements of both tissue and energy. Clearly note any areas that seem to be tense or closed to your breath. Spend at least 10 minutes on this stage of the practice.

1

Opening your breathing spaces

During exhalation, use two or three fingers to press gently into your lower abdomen, between your pubic bone and your navel. During inhalation, gradually release the pressure. Sense how your abdomen responds to this pressure. Take several breaths this way. Now put your hands over your navel, and work in the same way—pressing as you exhale, and gradually releasing the pressure as you inhale. Notice how your lower breathing space begins to open.

Next, put your hands over your lower ribs on both sides of your trunk. As you exhale, gently press your ribs inward with your hands. As you inhale, gradually release the pressure from your hands and sense your ribs expanding outward. It is helpful to realize that the lower ribs, also called the “floating ribs,” can expand quite freely since they are not attached to your sternum. In fact, the expansion of the floating ribs helps create more space for the lungs to expand at their widest point.

Now, apply light pressure to your solar plexus as you exhale. Again, watch for several minutes as your upper abdomen begins to relax and open. Next, as you exhale, press lightly on the bottom of your sternum. Taking several breaths in each position, gradually work your way up toward the top of the sternum. If you take your time and work gently, you will find your various breathing spaces beginning to become more elastic and spacious. Now try this same approach with any areas of your abdomen, rib cage (both on and between your ribs), shoulders, and so on that seem overly tight or constricted. Take your time. It is actually better to do this work for 15 or 20 minutes each day over a period of a week or so than to try to do it all in one session.

2

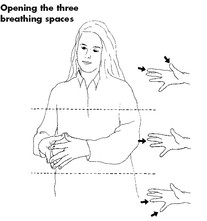

A simple technique for opening the three breathing spaces

There is another, simple technique that you can experiment with to help open the three breathing spaces. This technique, which I learned several years ago from Ilse Middendorf, involves pressing the appropriate finger pads of one hand against those of the other. To help open the lower space, press the pads of the little fingers and the pads of the ring fingers together firmly but without force. For the middle space, press the pads of the middle fingers together. For the upper space, press the pads of the thumbs and index fingers together. To help open all the spaces simultaneously, press the pads of all five fingers together (

Figure 29

). When you first begin this practice do not take more than take eight breaths while pressing your finger pads together.

3

Movement of spaciousness

Once you feel more of the whole of yourself involved in breathing, put most of your attention on the movement of air through your nose during inhalation. Take several long, slow breaths. Feel the empty, expansive, spacious quality of the air as it moves down through your trachea and into your lungs. But don’t stop there. As you continue your inhalation, sense this spaciousness moving downward through all the tissues and organs of your abdomen and filling your entire lower breathing space. Allow this feeling of space to release any tensions and absorb any stagnant energies residing below your navel. As you exhale slowly, use your attention to direct these tensions and energies out with your breath. Then work in the same way with the middle breathing space (from the navel to the diaphragm) and with the upper breathing space (from the diaphragm to the top of the head), sensing the various tissues and organs inside these spaces. When you have worked with all three breathing spaces, stop working intentionally with the feeling of space and simply follow your breathing.

4

Sensing the breath of the spine

Now that you have some direct awareness of the three major breathing spaces, especially in relation to the front of the body, we’re going to work with the inner space of the spine, the very core of our body, which connects the three breathing spaces in the back. In particular, we’re going to sense the craniosacral rhythm of the cerebrospinal fluid as it pulses through the central canal of the spine, moving from the brain down to the sacrum. The cerebrospinal fluid—a clear fluid produced from red blood flowing through a rich supply of blood vessels deep within the brain—not only provides nutrients for the brain and spine, but also removes the toxic products of metabolism and functions as a shock absorber. The pressure of this fluid has an influence on nerve flow and affects the ability of the senses and brain to take in new impressions.

Lie down on your back with your legs stretched out and your arms at your side. Sense again the expansion and contraction of your breath as it moves through the three breathing spaces, the three burners. See if you can include your heartbeat in your sensation. After several minutes, put your fingers on your temples above your ears (you can rest your elbows on the ground) and sense the pulse of your heartbeat in your temples. Sense the way your head expands on inhalation and contracts on exhalation. You may also begin to feel the way your whole body takes part in this ongoing rhythm of expansion and contraction.

After two or three minutes working in this way, hold your breath intentionally after inhaling. See if you can sense an inner expansion and contraction radiating from the area of the head and spine. Make sure that you don’t hold your breath for any longer than is comfortable. After taking several more spontaneous breaths, again hold your breath and touch the tip of your tongue to the center of the roof of your mouth. Later in the book we will go into the significance of this in completing the circuit of energy flow called the microcosmic orbit, but for now just see if you can sense the roof of your mouth expanding and contracting in rhythm with your head and spine. If so, what you are sensing is the pulsation of your cerebrospinal fluid. An entire cycle of expansion and contraction can take from five to eight seconds.

5

Sense your spine and breathing spaces at the same time

Now without losing touch with the “breathing” of your spine, include the three breathing spaces in your sensation of yourself. As you sense the pulsation of your spine, also sense the three breathing spaces as they empty and fill. As you exhale, the spaces contract from top to bottom. As you inhale, the spaces expand from bottom to top.

Don’t force anything.

Just let yourself experience the process of natural breathing—a process in which the various spaces of your body all participate. Feel how with each breath the spaces are becoming “large and roomy.” Let your awareness enter these spaces and enjoy the comfort of this natural process of expansion and contraction. After several minutes, get up and either sit cross-legged or on a chair. Continue to work with spacious breathing for several more minutes, noticing any changes brought about by your new posture.

6

The pause of spaciousness

Now simply follow your breathing. Notice the two pauses in your breathing cycle: one after inhalation and one after exhalation. Pay particular attention to the pause after exhalation. The great mystical traditions have spoken of this pause between exhalation and inhalation as a timeless moment—an infinite space—between yin and yang, nonaction and action, in which we can go beyond our self-image and experience our own unconditioned nature. See if you can at least sense this pause as an entranceway into yourself—into the healing spaciousness of your own deepest sensation of yourself. Don’t try to force anything. Just watch and sense. Work like this for at least 10 minutes.

7

Spacious breathing under stress

It is relatively easy to have the sense of spaciousness when we are in quiet, undemanding circumstances. And it is important, especially at the beginning, to practice this kind of breathing in such circumstances. Eventually, however, you will want to begin to try spacious breathing, especially into your navel area, in the often stress-filled circumstances of your everyday life. For it is here that you will, with practice, have the largest impact on your overall well-being and health, and it is here that you will gain important new insights into your own nature. What’s more, it is here that you will have an opportunity to discover a deep inner sensation of yourself that is somehow “separate” from the automatic reactions of your sympathetic nervous system (your “fight or flight” reflex), an overall sensation of yourself that will, if you can stay in touch with it, dissolve any unnecessary tension and bring about the appropriate degree of relaxation to meet the real demands of the moment.

To help prepare for working in such conditions, try the following practice. Stand with your weight balanced equally on both feet and your knees slightly bent. Sense the whole of yourself standing there, breathing. Let the sensation of yourself go deeper and deeper with each breath. Without losing this overall sensation of yourself, let your weight shift to your right foot. Bring your left foot up along the inner side of your right leg all the way up to your groin. Use your hands to help you position the heel of your foot in the area of your groin with your toes pointed upward if possible. Now raise your arms up from your sides (palms facing up) until your palms meet over your head (

Figure 30

). If this posture is too easy for you, if it does not arouse any stress, you might try closing your eyes and moving your arms up and down as you stand on one leg. If your health will not permit you to stand on one leg or to raise your arms above your head, then be inventive—find other ways to make the posture challenging for yourself.