The Taste of Conquest (29 page)

Read The Taste of Conquest Online

Authors: Michael Krondl

Whatever good and bad can be said of the consequences of da Gama’s and Columbus’s trips across the oceans in search of spices and paradise—and there is no shortage of either—they had the effect of undamming the flow of humanity and commerce across the earth. The silver that was mined in Mexico now influenced currency markets in China. An increase in the demand for pepper in Europe led to changes in production techniques in India. The labor requirements of Portuguese sugar plantations in Brazil had repercussions deep within Africa. People in Lisbon and Madrid made decisions that directly affected the lives of people halfway around the world. The Venetian ambassador to Manuel I had no illusions about the immensity of these transformations: “What is greatest and most memorable of all, you have brought together under your command peoples whom nature divides, and with your commerce you have joined two different worlds.” The wheels of globalization were sent spinning by the wake of the great

naus

that took leave of the little white tower at Bélem.

Tell any Lisbon native that you are going to this historic suburb and her mouth will curl into a lip-smacking smile. Naturally, every visitor to Lisbon must make a pilgrimage to Belém’s national shrine. But don’t think for a moment that what she has in mind are the Mosteiro dos Jerónimos and the Torre de Belém. “They are nice, of course,” the

Lisboeta

sniffs regarding these architectural jewels, “but you really must go for the

pastéis de Belém.

” The citizens of Lisbon are impassioned about their sweets. A sweet muffinlike

bolo

is a typical breakfast; lunch might conclude with any one of a dozen variations of

pudim

(the term

flan

could hardly begin to describe the myriad variations in color and texture). Other desserts are so peculiarly Portuguese that the English language could not possibly do them justice. I am convinced that the city holds more pastry shops per capita than any other place on earth. A recent search of Lisbon’s Yellow Pages indeed turns up more than eight hundred

pastelarias

in the capital alone. (A similar search on much larger Paris yields only about 180!) Most Portuguese pastries use plenty of eggs, many are scented with cinnamon, and all of them are very sweet. All this comes together in what is the national dessert, the

pastéis de nata,

in Belém rechristened the

pastéis de Belém.

It is perhaps not entirely coincidental, then, that the high temple of this custard tart, the Casa dos Pastéis de Belém, should be located just between the president’s pink-tinted palace and the nation’s pantheon at the Jerónimos, where the country’s greatest kings, heroes, and poets lie interred. On weekend afternoons, the pastry shop’s bar is crowded four deep as visitors and locals alike wait for their turn to nibble the still-warm confection downed with a creamy espresso.

Today’s Portuguese don’t spend much time thinking about their history. In this, they are much like people everywhere. Hernâni Xavier would like to blame the gays and communists who he claims run the Ministry of Education, but even he admits that the sixteenth century is of little concern to his countrymen. Heroism is not in fashion in the European Union, and most of the citizens of what used to be called Christendom would prefer not to be reminded of the jihadist fervor that launched “the age of discovery.” To most of his countrymen, Camões is just the name of a street, a square, an institute. When, in school, they read the great poet’s epic account of their ancestors (“risking all / In frail timbers on treacherous seas, / by routes never charted, and only emboldened by opposing wind; / having explored so much of the earth / from the equator to the midnight sun [they were] drawn / to touch the very portals of the dawn”), it is no more than literature. You can hardly expect the descendants of those Lusitanians to make the connection between Camões’s ancient, stubborn seamen sailing round an unknown world and the cinnamon on their

pastéis de Belém,

to remember the complaint of another Portuguese poet who lamented, “At the scent of this cinnamon, the kingdom loses its people.”

And yet, the stories those little custard tarts could tell. You could distill Portugal’s past into a single bite. The delicate flaky pastry that shatters on the tongue is a souvenir of the Moors who brought the technique of making phyllolike pastry to Iberia. The generous sprinkle of cinnamon is like so much aromatic dust, all that’s left of the long-lost Asian empire. Then there’s the sugar brought by the Portuguese to America, a memento of the continent found by accident on the way to the spiceries, a reminder of the sweet cane that sent helpless Africans to suffer and die across the sea and dispatched shiploads of the white crystals to pastry shops from Lisbon to Vienna. All this history bound up with creamy, cinnamon-scented custard.

S

WEETS

, S

PICES, AND

S

AINTS

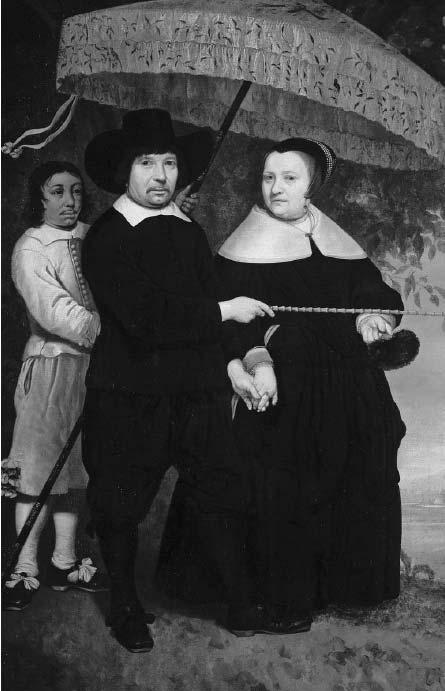

I spotted the two

Zwarte Pieten

just in time, as they were getting ready to pack up and lug their sweet-filled sack across the canal. The black-faced figures were the only splash of color in the fading December light, the velvet of their red, yellow, and green tunics glistening from the interminable Amsterdam drizzle. Across the street, I could see little of their dark-painted faces except for the broad carmine grins and the flash of fine Dutch teeth as they watched me slip and slide across the slick cobblestones. I looked neither left nor right and made a dash for it—like the fool that I am. A hurtling bicycle almost sent me headfirst into the canal. Luckily, the grandmotherly bicyclist swerved her steed at the last minute, even though I think her expert maneuver was less out of concern for my safety than to keep the tower of pastry-shop cartons from toppling out of her basket.

It was December 5, the eve of

Sinterklaas,

the feast of Saint Nicholas. Dutch grandmothers mark the occasion by spoiling their grandchildren with all manners of sweets. Parents hide presents in wooden shoes and broom closets. And numberless blond, blue-eyed Netherlanders paint their faces black and dress up like Renaissance house slaves, as

Zwarte Pieten

(“Black Petes”)—the name given to Saint Nick’s “African” helpers. They hang out on street corners and in shopping malls, distributing

pepernoten

to every passerby. The spicy cookies, the campy blackface—they’re as Dutch as windmills and wooden shoes. But they are also somewhat creepy souvenirs of the country’s colonial history, of Amsterdam’s once-great empire of sugar and spice.

Pepernoten

are a kind of small, dark cookie made with brown sugar and a medley of spices that varies depending on the region and the manufacturer. Despite the name, and unlike Venetian

pevarini,

they are unlikely to contain any pepper to speak of, but no matter what their flavoring—some are now even being dipped in chocolate, to the horror of purists—they are as essential to Saint Nicholas Day as old Saint Nick himself and his swarthy sidekicks.

The white-bearded saint dressed in red would be familiar to any American child who has visited a mall in the weeks before Christmas. Our own Santa Claus is largely based on the Dutch original. In the Netherlands, though, he’s supposed to represent a semimythical fourth-century bishop from the balmy city of Myra (in today’s Turkey) rather than a frost-flushed elf from the wintry pole. In the Middle Ages, his claim to fame was as the patron saint of merchants and sailors, so it was only natural that the up-and-coming seaport of Amsterdam would appoint Nicholas as the city’s official saint.

*39

Records as early as 1360 describe a

Sinterklaas

celebration for children. According to tradition he showed up in medieval Dutch convent schools, where he rewarded deserving pupils with spicy sweets and left behind a birch switch for thrashing ne’er-do-wells. Soon enough, the bushy-bearded visitor became associated with handing out presents, too. In medieval Amsterdam, the city’s central Dam Square was taken over each year by a

Sinterklaas

market, where the booths overflowed with sweets like cinnamon bark, honey tarts, and

pepernoten,

all distinctly flavored with the sugar and spices imported from the bishop’s home in the mythical East. All this fun was too much for the Calvinists when they took over during the Reformation, so they tried to ban the rotund saint, indicting him as an idolatrous Papist puppet. “The setting up of booths on St. Nicholas Eve where goods are sold, which St. Nicholas is said to provide, leads the children astray, and such a practice is not only contrary to all good order, but also leads the people away from the true religion and tends toward atheism, superstition and idolatry,” ran the text of one anti-

Klaas

injunction from 1600. In town after town, measures were taken to ban the baking of spicy

Sinterklaas

cakes and setting out shoes for presents. But it was to no avail. Old Saint Nick was just too popular.

Nowadays,

Sinterklaas

supposedly arrives a few weeks before the December 5 holiday on a steamship from Spain—an event that is widely covered by every TV network. The saint is accompanied by a white horse and one or more

Zwarte Pieten.

You will hear that

Zwarte Piet

is supposed to be a Spanish Moor, but that’s a relatively recent idea. In earlier times, the black-faced Pete typically represented the Devil and was often shackled in chains. Today’s Pete, with his frilly outfit and campy wig, looks like he stepped out of a nineteenth-century minstrel show. The look is hardly coincidental. This particular incarnation of

Piet

was invented at about the same time as those racist cabarets, at just about the time Holland abolished slavery in its colonies in 1863—incidentally, one of the last European states to do so. The Surinamese government had no illusion about what

Zwarte Piet

represented when it gained independence from the Netherlands in 1975 and promptly abolished the black-faced figure. In the sugar plantations of Suriname (formerly Dutch Guiana), they had their own opinion of dressing up black men in shackles. All the same,

Piet

was so popular that he was reinstated in 1992.

Of course, back in Holland, the Dutch would be no more likely to associate

Zwarte Piet

with the horrors of the Middle Passage than they would think of the genocide their forefathers perpetrated in the Indonesian nutmeg isles as they nibble their spice-scented

pepernoten.

In this, they are much like the Portuguese, mostly oblivious to the loss of their sugar colonies in the Americas and their Spice Islands in Indonesia, though, again like da Gama’s heirs, they remain adamant when it comes to their love of sweets. The Dutch sweet tooth has a taste for spicy sweets that is almost medieval when compared to the Portuguese—at least when it comes to the confections traditionally eaten around

Sinterklaas

and Christmas. If you can believe the statistics, the Netherlands’ fifteen million people consume some sixty-two million pounds of spice cake every year!