The Third Reich at War (64 page)

There were 140,000 Jews living in the Netherlands when the German armed forces invaded in 1940, of whom 20,000 were foreign refugees. The native Dutch Jews belonged to one of the oldest established Jewish communities in Europe, and antisemitism was relatively limited in scope and intensity before the German occupation. But the strong position of the Nazi and in particular the SS leadership in the absence of a Dutch government, and the antisemitic convictions of the almost wholly Austrian occupation administration, lent a radical edge to the persecution of Dutch Jews. In addition, ironically, since Hitler and the leading Nazis regarded the Dutch as quintessentially Aryan, the need to remove the Jews from Dutch society seemed particularly urgent. The German administration began almost immediately to institute anti-Jewish measures, limiting and then in November 1940 ending Jewish participation in state employment. Jewish shops had to be registered and so too, on 10 January 1941, were all Jewish individuals (defined roughly as in the Nuremberg Laws). With the inevitable emergence of a native Dutch Nazi Party, tensions began to mount, and when the Jewish owners of an ice-cream parlour in Amsterdam attacked a pair of German policemen under the mistaken impression that they were Dutch Nazis, German forces surrounded the Jewish quarter of the city and arrested 389 young men, who were deported to Buchenwald and then to Mauthausen. Only one of them survived. Numerous protests were directed by Dutch academics and from the Protestant Churches (except the Lutherans) at the antisemitic policies of the occupiers. The Dutch Communist Party declared a general strike that brought Amsterdam to a virtual standstill on 25 February 1941. The German occupying authorities responded with massive and violent repression, in which a number of protesters were killed and the strike brought to a swift end. Another 200 young Jews, this time refugees from Germany, were tracked down, arrested and sent to their deaths in Mauthausen after a small group of resisters launched bold but futile attack on a German air force communications centre on 3 June 1941.

177

The situation of Dutch Jews became truly catastrophic following the Eichmann conference of 11 June 1942. Already on 7 January 1942, acting on German orders, the Jewish Council of Amsterdam, responsible for the Jews in the whole country since the previous October, began ordering unemployed Jews into special labour camps at Amersfoort and elsewhere. Run mainly by Dutch Nazis, the camps quickly became notorious centres of torture and abuse. Another camp, at Westerbork, where German-Jewish refugees were detained, became the main transit centre for non-Dutch deportees to the East, while Dutch Jews were collected in Amsterdam before being loaded on to trains bound for Auschwitz, Sobibor, Bergen-Belsen and Theresienstadt. After fresh antisemitic legislation had been introduced, including a Dutch version of the German Nuremberg Laws and, in early May 1942, the compulsory wearing of the Jewish star, it became easier to identify Jews in Holland. The main burden of the business of rounding up, interning and deporting the Jews fell on the Dutch police, who participated willingly and, in the case of a 2,000-man force of voluntary police auxiliaries recruited in May 1942, with considerable brutality. In the usual way, the German Security Police in Amsterdam - about 200 men in all - forced the Jewish Council to co-operate in the deportation process, not least by allowing it to establish categories of Jews who would be exempt. Corruption and favouritism rapidly spread as desperate Dutch Jews used every means in their power to obtain the coveted stamp on their identity cards granting them immunity. Such immunity was not available to non-Dutch Jews, mostly refugees from Germany, many of whom therefore went into hiding - amongst them the German-Jewish Frank family, whose adolescent daughter Anne kept a diary that became widely known when it was published after the war.

178

Two members of the Jewish Council managed to destroy the files of up to a thousand mostly working-class Jewish children assembled in a central crèche and smuggled the children into hiding. But help from the mass of the Dutch population was not forthcoming. The civil service and the police were used to working with the German occupiers, and took a strictly legalistic view of the orders they were asked to implement. The leaders of the Protestant and Catholic Churches sent a collective protest to Seyss-Inquart on 11 July 1942, objecting not only to the murder of Jewish converts to Christianity but also to the murder of unbaptized Jews, the overwhelming majority. When the Catholic Bishop of Utrecht, Jan de Jong, refused to give in to intimidation from the German authorities, the Gestapo arrested as many Jewish Catholics as they could find, and sent ninety-two of them to Auschwitz. Despite this clash, however, neither the Churches nor the Dutch government in exile did anything to rouse the population against the deportations. Reports about the death camps sent to Holland both by Dutch SS volunteers and by two Dutch political prisoners who had been released from Auschwitz had no effect. Between July 1942 and February 1943 fifty-three trains left Westerbork, carrying a total of nearly 47,000 Jews to Auschwitz: 266 of them survived the war.

179

In the following months, a further 35,000 were taken to Sobibor, of whom a mere nineteen survived. A trainload of 1,000 Jews left the transit camp at Westerbork every Tuesday for week after week through all this period, and beyond, until over 100,000 had been deported to their deaths by the end of the war.

180

The Nazi administration in Holland went further in its antisemitism than any other in Western Europe, reflecting not least the strong presence of Austrians among its top leadership. Seyss-Inquart even pursued the sterilization of the Jewish partners in the 600 so-called mixed marriages registered in the Netherlands, a policy discussed but never put into action in Germany itself.

181

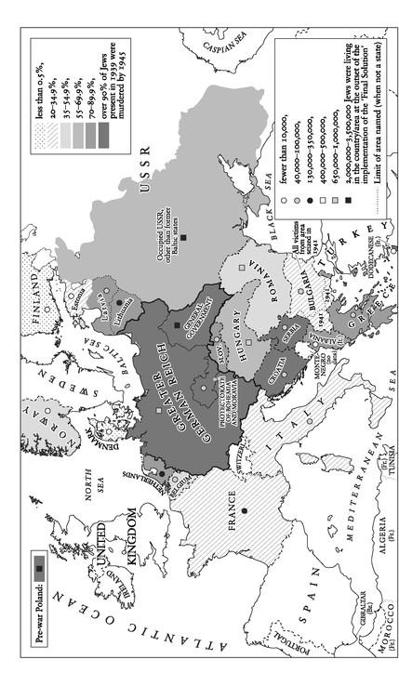

14. The Extermination of the European Jews

The contrast with neighbouring Belgium was striking. Between 65,000 and 75,000 Jews lived in Belgium at the beginning of the war, all but 6 per cent of them immigrants and refugees. The German military government issued a decree on 28 October 1940 compelling them to register with the authorities, and soon native Jews were being dismissed from the civil service, the legal system and the media, while the registration and Aryanization of all Jewish assets got under way. The Flemish nationalist movement set light to synagogues in Antwerp in April 1941 following a showing of an antisemitic film.

182

However, the German military government reported that there was little understanding of the Jewish question amongst ordinary Belgians, and feared hostile reactions should native Belgian Jews be rounded up. Most Belgians, it seemed, regarded them as Belgians. Himmler was willing for the moment to agree to a postponement of their deportation, and when the first train left for Auschwitz on 4 August 1942, it contained only foreign Jews. By November 1942 some 15,000 had been deported. By this time, however, a newly founded Jewish underground organization had made contact with the Belgian resistance, whose Communist wing already contained many foreign Jews, and a widespread action began to bring the country’s remaining Jews into hiding; many local Catholic institutions also played an important part in concealing Jewish children. In Holland, on the other hand, the Jewish community leadership was less active in assisting Jews to go underground. Quite possibly, too, the fact that the Belgian monarchy, government and civil service and police administration had remained in the country provided a buffer against the genocidal zeal of the Nazi occupiers, as did the effective control of Belgium by the German military, in contrast to the dominance in Holland of the Nazi Commissioner Seyss-Inquart and the SS. Certainly the Belgian police were less willing to assist in the round-up of Jews than were their colleagues in the Netherlands. As a consequence of all this, only 25,000 Jews were deported from Belgium to the gas chambers of Auschwitz; another 25,000 found their way into hiding. All in all, 40 per cent of Belgian Jews were murdered by the Nazis, an appalling enough figure; in the Netherlands, however, the proportion reached 73 per cent, or 102,000 out of a total of 140,000.

183

III

In pursuit of Hitler’s declared purpose of ridding Europe of the Jews, the pedantically thorough Heinrich Himmler also turned his attention to Scandinavia, where the number of Jews was so small as to have virtually no political or economic importance, and native antisemitism was far less widespread than in other Western European countries. He even visited Helsinki in July 1942 to try to persuade the government, which was allied to the Third Reich, to hand over the 200 or so foreign Jews who lived in Finland. As the Finnish police began compiling a list, news of the forthcoming arrests spread, and voices were raised in protest both within the government and beyond. Eventually the number was whittled down to eight (four Germans and an Estonian with their families), who were deported to Auschwitz on 6 November 1942. All save one were killed. The 2,000 or so native Finnish Jews were not affected, and after the Finnish government assured Himmler that there was no ‘Jewish question’ in the country, he abandoned any attempt to secure their delivery to the SS.

184

In Norway, under direct German occupation, Himmler’s task was simpler. The King and the government elected before the war had gone into exile in Britain, from where they broadcast regularly to the population. Resistance to the German invasion had been strong, and the installation of a puppet government under the fascist Vidkun Quisling had failed to produce the mass popular support for collaboration with the German occupiers that its leader had promised. Growing shortages of food and raw materials, like everywhere else in Western Europe, had done little to win over the population. The majority of Norwegians remained opposed to the German occupation, but unable for the moment to do much about it. Behind the scenes, the country was effectively ruled by Reich Commissioner Josef Terboven, the Nazi Party Regional Leader in Essen. There were about 2,000 Jews in Norway, and in July 1941 the Quisling government dismissed them from state employment and the professions. In October 1941, their property was Aryanized. Shortly afterwards, in January 1942, the Quisling government ordered the registration of the Jews according to the definition of the Nuremberg Laws. In April 1942, however, recognizing Quisling’s failure to win public support, the Germans dismissed his government, and Terboven began to rule directly. In October 1942 the German authorities ordered the deportation of the Jews from Norway. On 26 October 1942 the Norwegian police began arresting Jewish men, following this on 25 November with women and children. 532 Jews were shipped to Stettin on 26 November, followed by others; in all, 770 Norwegian Jews were deported, of whom 700 were gassed in Auschwitz. 930, however, managed to flee to Sweden, and the rest survived in hiding or escaped in some other way.

185

Once the deportations of Jews from Norway began, the Swedish government decided to grant asylum to any Jews arriving in the country from other parts of Europe.

186

Neutral Sweden now took on a significant role for those trying to stop the genocide. The Swedish government was certainly well enough informed about it. On 9 August 1942 its consul in Stettin, Karl Ingve Vendel, who worked for the Swedish secret service and had good contacts with members of the German military resistance to the Nazis, filed a lengthy report that made it clear that Jews were being gassed in large numbers in the General Government. The authorities continued to grant asylum to Jews who crossed the Swedish border but refused to launch any initiative to stop the murders.

187

Hitler considered the Danes, like the Swedes and Norwegians, to be Aryans; unlike the Norwegians, they had offered no noteworthy resistance to the German invasion in 1940. It was also important to keep the situation in Denmark calm so that vital goods could pass to and fro between Germany and Norway and Sweden without hindrance. Denmark’s strategic significance, commanding a significant stretch of the coast opposite England, was vital. For all these reasons, the Danish government and administration were left largely intact until September 1942, when King Christian X caused Hitler considerable irritation by replying to his message of congratulation on his birthday with a terseness that could not be considered anything but impolite. Already irritated by the degree of autonomy shown by the Danish government, an angry Hitler immediately replaced the German military commander in the country, instructing his successor to take a tougher line. More significantly, he appointed the senior SS officer Werner Best as Reich Plenipotentiary on 26 October 1942. By this time, however, Hitler had calmed down, and Best was fully aware of the need not to offend the Danes, their government or their monarch by being too harsh. Somewhat unexpectedly, therefore, he operated to begin with a policy of flexibility and restraint. For several months he even urged caution in the policy adopted towards the Danish Jews, of whom there were about 8,000, and little was done to them apart from minor measures of discrimination, to which the leaders of the Jewish community did not object.

188