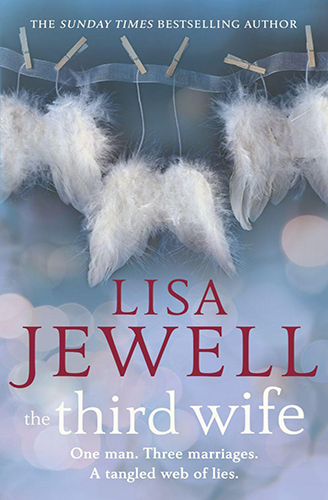

The Third Wife

Contents

In the early hours of an April morning, Maya stumbles into the path of an oncoming bus.

A tragic accident? Or suicide?

Her grief-stricken husband, Adrian, is determined to find out.

Maya had a job she enjoyed; she had friends. They’d been in love.

She even got on with his two previous wives and their children. In fact, they’d all been one big happy family.

But before long Adrian starts to identify the dark cracks in his perfect life.

Because everyone has secrets.

And secrets have consequences.

Lisa Jewell had always planned to write her first book when she was fifty. In fact, she wrote it when she was twenty-seven and had just been made redundant from her job as a secretary. Inspired by Nick Hornby’s

High Fidelity

, a book about young people just like her who lived in London, she wrote the first three chapters of what was to become her first novel,

Ralph’s Party

. It went on to become the bestselling debut novel of 1998.

Eleven bestselling novels later, she lives in London with her husband and their two daughters. Lisa writes every day in a local cafe where she can drink coffee, people-watch, and, without access to the internet, actually get some work done.

Get to know Lisa by joining the official facebook page at

www.facebook.com/LisaJewellOfficial

or by following her on Twitter

@lisajewelluk

. And visit her website at

www.lisa-jewell.co.uk

This book is dedicated to all my friends on the Board

One

April 2011

They might have been fireworks, the splashes, bursts, storms of colour that exploded in front of her eyes. They might have been the Northern Lights, her own personal aurora borealis. But they weren’t, they were just neon lights and street lights rendered blurred and prismatic by vodka. Maya blinked, trying to dislodge the colours from her field of vision. But they were stuck, as though someone had been scribbling on her eyeballs. She closed her eyes for a moment but, without vision, her balance went and she could feel herself begin to sway. She grabbed something. She did not realise until the sharp bark and shrug that accompanied her action that it was a human being.

‘Shit,’ Maya said, ‘I’m really sorry.’

The person tutted and backed away from her. ‘Don’t worry about it.’

Maya took exaggerated offence to the person’s lack of kindness.

‘Jesus,’ she said to the outline of the person whose gender she had failed to ascertain. ‘What’s your problem?’

‘Er,’ said the person, looking Maya up and down. ‘I think you’ll find you’re the one with the problem.’ Then the person, a woman, yes, in red shoes, tutted again and walked away, her heels issuing a mocking clack-clack against the pavement as she went.

Maya watched her blurred figure recede. She found a lamp post and leaned against it, looking into the oncoming traffic. The headlights turned into more fireworks. Or one of those toys she’d had as a child: tube, full of coloured beads, you shook it, looked through the hole, lovely patterns – what was it called? She couldn’t remember. Whatever. She didn’t know any more. She didn’t know what time it was. She didn’t know where she was. Adrian had called. She’d spoken to him. Tried to sound sober. He’d asked her if she needed him to come and get her. She couldn’t remember what she’d said. Or how long ago that had been. Lovely Adrian. So lovely. She couldn’t go home. Go home and do what she needed to do. He was too nice. She remembered the pub. She’d talked to that woman. Promised her she was going home. That was hours ago. Where had she been since then? Walking. Sitting somewhere, on a bench, with a bottle of vodka, talking to strangers. Hahaha! That bit had been fun. Those people had been fun. They’d said she could come back with them, to their flat, have a party. She’d been tempted, but she was glad now, glad she’d said no.

She closed her eyes, gripped the lamp post tighter as she felt her balance slip away from her. She smiled to herself. This was nice. This was nice. All this colour and darkness and noise and all these fascinating people. She should do this more often, she really should. Get out of it. Live a little. Go a bit nuts. A group of women were walking towards her. She stared at them greedily. She could see each woman in triplicate. They were all so young, so pretty. She closed her eyes again as they passed by, her senses unable to contain their image any longer. Once they’d passed she opened her eyes.

She saw a bus bearing down, bouncy and keen. She squinted into the white light on the front, looking for a number. It slowed as it neared her and she turned and saw that there was a bus stop to her left, with people standing at it.

Dear Bitch. Why can’t you just disappear?

The words passed through her mind, clear and concise in their meaning, like a sober person leading her home. And then those other words, the words from earlier.

I hate her too.

She took a step forward.

‘According to the bus driver, Mrs Wolfe lurched into the path of the bus.’

‘Lurched?’ echoed Adrian Wolfe.

‘Well, yes. That was the word he used. He said that she did not appear to step or jump or run or fall or slip. He said she lurched.’

‘So it was an accident?’

‘Well, yes, it does sound possible. But obviously we will need a full coroner’s report, a possible inquest. What we can tell you with certainty is that her blood alcohol reading was very high.’ DI Hollis referred to a piece of paper on the desk in front of him. ‘Nought point two. That’s extraordinarily high. Especially for a small woman like Mrs Wolfe. Was she a regular drinker?’

The question sounded loaded. Adrian flinched. ‘Er, yes, I suppose, but no more so than your average stressed-out thirty-three-year-old school teacher. You know, a glass a night, sometimes two. More at the weekends.’

‘But this level of drinking, Mr Wolfe? Was this normal?’

Adrian let his face fall into his hands and rubbed roughly at his skin. He had been awake since 3.30 a.m., since his phone had rung, interrupting a fractured dream in which he was running about central London with a baby in his arms trying to call Maya’s name but not able to make a sound.

‘No,’ he said, ‘no. That wasn’t normal. She isn’t … wasn’t that kind of drinker.’

‘So, what was she – out at a party? Doing something out of the ordinary?’

‘No. No.’ Adrian sighed, feeling the inadequacy of his understanding of the night’s events. ‘No. She was looking after my children. At my house in Islington …’

‘

Your

children?’

‘Yes.’ Adrian sighed again. ‘I have three children with my former wife. My former wife had to go to work today. Sorry. Yesterday. Unexpectedly. She didn’t have time to organise childcare so she asked if Maya would look after the children. They’re on their Easter holidays. And, obviously, Maya being a teacher, so is she. So Maya spent the day there and I was expecting her home at about six thirty and she wasn’t there when I got home and she wasn’t answering her phone. I called her roughly every two minutes.’

‘Yes, we saw all the missed calls.’

‘She finally picked up at about ten p.m. and I could tell she was drunk. She said she was in town. Wouldn’t tell me who with. She said she was on her way home. So I sat and waited for her. Called again from roughly midnight to about one o’clock. Then I finally fell asleep. Until my phone rang at three thirty.’

‘How did she sound? When you spoke to her at ten p.m.?’

‘She sounded …’ Adrian sighed and waited for a wave of tears to pass. ‘She sounded really jolly. Happy drunk. She was calling from a pub. I could hear the noise in the background. She said she was on her way home. She was just finishing her drink.’

‘Often the way, isn’t it?’ the policeman said. ‘When you’ve reached a certain point of inebriation. Much easier to be persuaded into staying on for that one more drink. The hours pass as fast as minutes.’

‘Do you have any idea who she was with, in that pub?’

‘Well, no. For now, we’re not treating Mrs Wolfe’s death as suspicious. If it becomes apparent that there was foul play involved and we need to investigate Mrs Wolfe’s last movements, then yes, we’ll talk to local publicans. Talk to Mrs Wolfe’s friends. Build up a fuller picture.’

Adrian nodded. He was tired. He was traumatised. He was confused.

‘Do you have any theories of your own, Mr Wolfe? Was everything OK at home?’

‘Yes, God, yes! I mean, we’d only been married two years. Everything was great.’

‘No problems with family number one?’

Adrian looked at DI Hollis questioningly.

‘Well, second wives – there can be, you know, pressures there?’

‘Actually, she’s … she

was

… my third wife.’

DI Hollis’s eyebrows jumped.

‘I’ve been married twice before.’

DI Hollis looked at Adrian as though he had just performed an audacious sleight-of-hand trick.

And now, ladies and gentlemen, for my next trick I will confound all your preconceptions about me in one fell swoop.

Adrian was used to that look. It said: How did an old fart like you manage to persuade one woman to marry you, let alone three?

‘I like being married,’ said Adrian, aware even as he said it how inadequate it sounded.

‘And that was all fine, was it? Mrs Wolfe wasn’t finding it difficult being in the middle of such a …

complicated

situation?’

Adrian sighed, pulled his dark hair off his face and then let it flop back over his forehead. ‘It wasn’t complicated,’ he said. ‘It isn’t complicated. We’re one big happy family. We go on holiday together every year.’

‘All of you?’

‘Yes. All of us. Three wives. Five children. Every year.’

‘All in the same house?’

‘Yes. In the same house. Divorce doesn’t have to be toxic if everyone involved is prepared to act like grown-ups.’

DI Hollis nodded slowly. ‘Well,’ he said, ‘that’s nice to hear.’

‘When can I see her?’

‘I’m not sure.’ DI Hollis’s demeanour softened. ‘I’ll talk to the coroner’s office for you now, see how they’re getting on. Should be soon.’ He smiled warmly and replaced the lid of his biro. ‘Maybe time to get home, have a shower, have a coffee?’

‘Yes,’ said Adrian. ‘Yes. Thank you.’

The key sounded terrible in the lock of Adrian’s front door; it ground and grated like an instrument of torture. He realised it was because he was turning the key extra slowly. He realised he was trying to put off the moment that he walked into his flat,

their

flat. He realised that he did not want to be here without her.

Her cat greeted him in the hallway, desperate and hungry. Adrian glanced at the cat blankly. Maya’s cat. Brought here three years ago in a brown plastic box as part of an endearingly small haul of possessions. He wasn’t a cat person but he’d accepted her cat into his world in the same way that he’d accepted her bright floral duvet cover, her wipe-clean tablecloth and her crap CD player.

‘Billie,’ he said, closing the door behind him, leaning heavily against it. ‘She’s gone. Your mummy. She’s gone.’ He slid slowly to his haunches, his back still pressed against the front door, the heels of his hands forced into his eye sockets, and he wept.