The Tiger Warrior (33 page)

Authors: David Gibbins

“And Howard?”

“He was the last sapper officer out of Rampa, months later, the only one who could withstand the malaria, probably because of his Indian childhood. The death of his eighteen-month-old son Edward in Bangalore while he was in the jungle was a terrible blow. Howard had been slated for great things as a soldier but opted for the engineer route, joining the Indian Public Works Department and then returning to England, to the School of Military Engineering at Chatham. He taught survey to young officers and immersed himself in the academic life of the corps. He became an ardent supporter of the movement that eventually led to the universal language Esperanto. Perhaps the urge came from his experience in Rampa, where they hadn’t been able to speak the Kóya language without an interpreter. Maybe it was some kind of atonement. He only returned to India once his children had grown up and gone to boarding school. I always assumed that his career decision had a lot to do with his son Edward, with his need to provide a better home for his children, in England. But now I think there was more to it than that. I think it goes back to that day in the jungle in 1879. And I don’t mean what they might have seen in the shrine. I mean something else, something he saw or did, that traumatized him. Maybe it was human sacrifice. Something he was powerless to stop.”

“Not exactly the glorious image of soldiering,” Costas said.

Pradesh shifted and cleared his throat. “I can sympathize. The worst thing for a soldier is being sent on a mission where you don’t have the political will or the resources to finish the job. I’ve experienced it, on a peacekeeping mission in Africa. Being powerless to stop genocide. If you do intervene, you may ease one person’s suffering, but it can make the feeling of impotence worse. One of my sappers shot a woman who’d been terribly mutilated. He was haunted by her face. He said that all the faces that previously had been one mass of tormented humanity had suddenly become real individuals, and that was what made it intolerable for him. He had nightmares about them all coming to him, asking why he hadn’t chosen to end their suffering too. He couldn’t live with it, and shot himself.”

Jack saw Rebecca’s face, and he squeezed her hand. “It could have been like that for Howard,” he said quietly. “So little knowledge of the emotional response to trauma has survived from the Victorian period. Yet men brought up on romance and courtly deeds ended up seeing and doing terrible things. They internalized these experiences all their lives, somehow using the reservoir of manly Victorian courage to live with it, bottling it up to the end.”

“You said he went back to India,” Costas said.

“That’s where it gets really fascinating,” Jack replied. “He returned to the Public Works Department, building bridges, canals, roads, and was principal of a college for native engineers. Then, in 1905, aged fifty, he finally returned to real soldiering. He became commanding royal engineer of the Quetta Division of the Indian army, up against the Afghan frontier in Baluchistan. It was one of the hot spots of the British Empire, about the most dangerous place in the world. Howard relished it, and for a while it was as if he were making up for lost time. But then, in 1907, a full colonel, he abruptly took half-pay and retired.”

“Quetta,” Costas murmured. “The same place Wauchope was?”

“Exactly,” Jack exclaimed. “That’s the linchpin of the story. After Rampa, the two men part ways. Perhaps in their pact in the jungle they mapped out their future, the time when they’d get together again. They coincide once, in 1889, when Wauchope takes a refresher course at the survey school at Chatham. They even co-author a paper, on the Roman coins of south India. They were meant to present it jointly at the Royal United Services Institute in London, but Wauchope was recalled to duty. Next, they appear together in Quetta almost twenty years later, in 1907, both retired. They dine as honored guests in the regimental messes, they meet the explorer Aurel Stein, they spend hours in the bazaar talking to travelers, equipping themselves. And then, one morning in April 1908, they gear themselves up, hobnailed boots and puttees, tweed jodhpurs, sheepskin coats, turbans, rucksacks, revolvers. Two old colonels off on a final great adventure. Quetta has seen this kind of thing before. Howard’s Tibetan servant Huang-li waves them off He’s been with Howard over the years, since Howard was taken as a boy to a refuge in Tibet during the Indian Mutiny. Huang-li is never seen again either. The two colonels march off toward the Bolan Pass into Afghanistan, and disappear into the great cleft in the mountains. That’s the last anyone hears of them.”

“That’s so cool,” Rebecca said. “Its just like

The Man Who Would Be King

, Kipling’s story. Now I know why you put that on the top of the pile for me to read on

Seaquest II

, Dad. Two British soldiers disappearing into the mountains, in search of treasure.”

“Treasure?” Costas said.

“I think Rebecca’s one step ahead,” Jack murmured.

“Chip off the old block,” Pradesh said, grinning.

“So what’s the pull for these guys, of Afghanistan?” Costas said.

“Adventure. War.” Pradesh clicked open a small case on his lap. Inside was a row of eight medals—three elaborate stars on the left and three service medals on the right, two of them with multiple campaign clasps over the ribbons. “These are Wauchope’s medals. Before disappearing he bequeathed all of his military possessions to the Regimental Mess of the Madras Sappers, with instructions that they should be auctioned among the officers and the proceeds distributed to famine relief charities. As a young officer before Rampa he had been in Madras during the terrible famine of 1877, and it affected him deeply. But by the time an inquest was held in 1924 into the disappearance and the two men were declared dead, there was little interest in the medals. They’ve been languishing in the museum storeroom at Bangalore ever since. I felt that they should be in the old headquarters of the Survey of India, where they’d be displayed alongside the memorabilia of the other pioneers. These men are remembered for committing their lives to mapping India and improving the welfare of the people. They are remembered by their Indian and Pakistani successors with pride and affection.”

“Isn’t the northwest frontier headquarters in what’s now Pakistan?” Costas said.

“That’s another reason why I’m coming with you to Kyrgyzstan,” Pradesh replied cheerfully. “There’s a Pakistani sapper contingent attached to the coalition base at Bishkek. I purchased the medals myself under the terms of Wauchope’s will, and saw that the money went to charity. I’m going to pass them to the commanding officer of the Pakistani sappers and he’ll see them safely to the museum.”

“I thought you guys were at war,” Costas said.

“Only our countries. Major Singh and I are close friends. We were both seconded at the same time to instruct in jungle survey at the School of Military Engineering at Chatham. That’s how I knew something of Howard and Wauchope’s later careers, from the records there. When Jack first told me about his interest in the Rampa Rebellion, I was stunned. I had no idea he was from the same Howard family.”

Costas peered at the medals. “Those two on the right, with the clasps. Different campaigns?”

Pradesh nodded. “Those are the Indian General Service Medals, with clasps for Hazara, Waziristan, Tirah. As a survey officer, Wauchope was involved in almost all of the Afghan frontier expeditions of the 1880s and 1890s.”

“But no clasp for Rampa,” Jack said.

Pradesh shook his head. “The government considered the rebellion a civil disturbance. It was a matter of politics, keeping it hush-hush. Nobody wanted internal unrest to be advertised in the wake of the Indian Mutiny. They agreed to consider it as active service in the soldiers’ records, but no medal was given.”

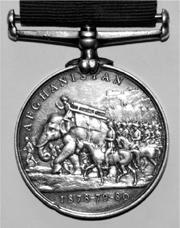

“And this one?” Costas pointed at the third campaign medal.

“The Afghan War of 1878 to 1880. Wauchope was there, as assistant engineer in the Bazar Valley Field Force, before being deployed to Rampa.” He lifted the medal up and turned it over.

Costas’ eyes lit up. “An elephant!”

Jack grinned at Pradesh. “I have to apologize for my friend. He has an elephant fixation. We found some underwater off Egypt.”

“Underwater?” Pradesh looked incredulous. “Did I hear you right? You found elephants underwater?”

“Later.”

Rebecca leaned across and touched the medal. “It looks just like Hannibal in the Alps,” she murmured. “My mother told me about that once when we met, and I did a drawing of it. So they used elephants in Afghanistan too. That’s so cool.” Jack smiled at her, and looked over. It was a beautiful medal, hanging from a red and green ribbon. On the obverse was Queen Victoria, Empress of India. On the reverse was a column on the march, with cavalry and infantry, dominated by an elephant carrying dismantled field guns on its back. Behind it was a towering mountain range, and in the exergue the word

Afghanistan

and the dates

1878-79-80

. It was the medal John Howard would have received had he joined the Khyber Field Force after the jungle, as he was slated to do. Had the Rampa Rebellion not strung on for months longer than expected. Had he not been the only officer to withstand the fever. Had his son Edward not become ill, and had another officer not offered to take his place in Afghanistan, to allow him to be closer to his family. It was a gesture of kindness that made no difference at all, as Edward had died so quickly while Howard was still in the jungle. To Jack the medal seemed to represent all the odd quirks of fate, and the anguish of loss. Plenty of sapper officers had died in Afghanistan. Had Howard gone there, it was possible that Jack would not have been here today.

Costas suddenly saw something, and pressed his nose against the window. “Holy cow. What was that?”

They followed his gaze. A line of red flashes punctuated the darkness far below. “Airstrike against a mountain ridge,” Pradesh murmured. “American or British warplanes, maybe Pakistani, low-flying. We’re over the Taliban heartland now. Bandit country.”

“Do we have any countermeasures? The chaff dispensers?” Costas said, looking at Jack anxiously.

“We’re flying high, over forty thousand feet. The Taliban have nothing that can get us. The Americans didn’t supply the mujahedin in the 1980s with anything bigger than the Stinger, and those are mostly gone.”

“Right,” Costas said. “I forgot. We armed these guys.”

“Before the Russians arrived, the Afghans mainly had old British weapons, hangovers from the Great Game,” Pradesh said. “Lee-Enfield rifles, Martini-Henrys, even Snider-Enfields from the 1860s. They made their own imitations, the so-called Khyber Pass rifles. These weapons are still around today and not to be underestimated. The Afghans were brilliant marksmen with their own homegrown guns, the matchlock jezails. With British rifles they were superb. This is sniper country, huge vistas with lots of upland vantage points. The traditional Afghan marksman despises the Taliban recruit who sprays the air with his Kalashnikov while shouting jihadist slogans. He despises him for his poor marksmanship as much as for his Wahabist fanaticism. Afghan society is one where violent death is omnipresent, but within an honorable tradition. No Afghan warrior wants to die. He’s contemptuous of the suicide bomber. He loathes fundamentalism. The martyr mentality and the Kalashnikov, those are the two weak points in the Taliban armor.”

“Sounds like this war should be won for us by the Afghans,” Costas said.

“A few hundred Afghan mountain men armed with sniper rifles could cripple the Taliban. The Afghans just have to be persuaded that the Taliban are their worst enemy. And they need to know that the coalition will stay on afterward to rebuild the country.”

“A lot of work for sappers,” Costas said.

“We’re all ready for it,” Pradesh replied enthusiastically. “My fellow officers and I have pored over all the archives from the 1878 war, when the Madras Sappers built bridges in the Khyber Pass. We could do it again.” They looked up as the copilot came down the aisle, gesturing at Pradesh. “My turn to fly,” Pradesh said, getting up. “I need to get my fixed-wing log up to date. See you later.”

“Dad.” Rebecca was looking at the book on her lap again. “I’ve just noticed. There’s something in pencil, in the margin. I can barely read it.”

“What’s the book?” Costas asked.

“Wood’s

Source of the River Oxus,”

Jack said. “From my cabin. Howard’s own copy. I showed it to you earlier.”

“Oh, yeah. Fascinating stuff on mining.”

“While you were all snoring away, I got to the part where he discovers the lapis lazuli mines,” Rebecca said. “It’s incredibly exciting. It’s like an adventure novel. He says there were three grades of lapis.” She read out a passage:

“These are the

Neeli,

or indigo color; the

Asmani,

or light blue; and the

Suvsi,

or green

. He says the Neeli is the most valuable.

The richest colors are found in the darkest rock, and the nearer the river the greater is said to be the purity of the stone.”

“Neeli,”

Costas said. “Sounds like

Nielo

, from the tomb in

scrip

ti

on-sappheiros nielo minium.”