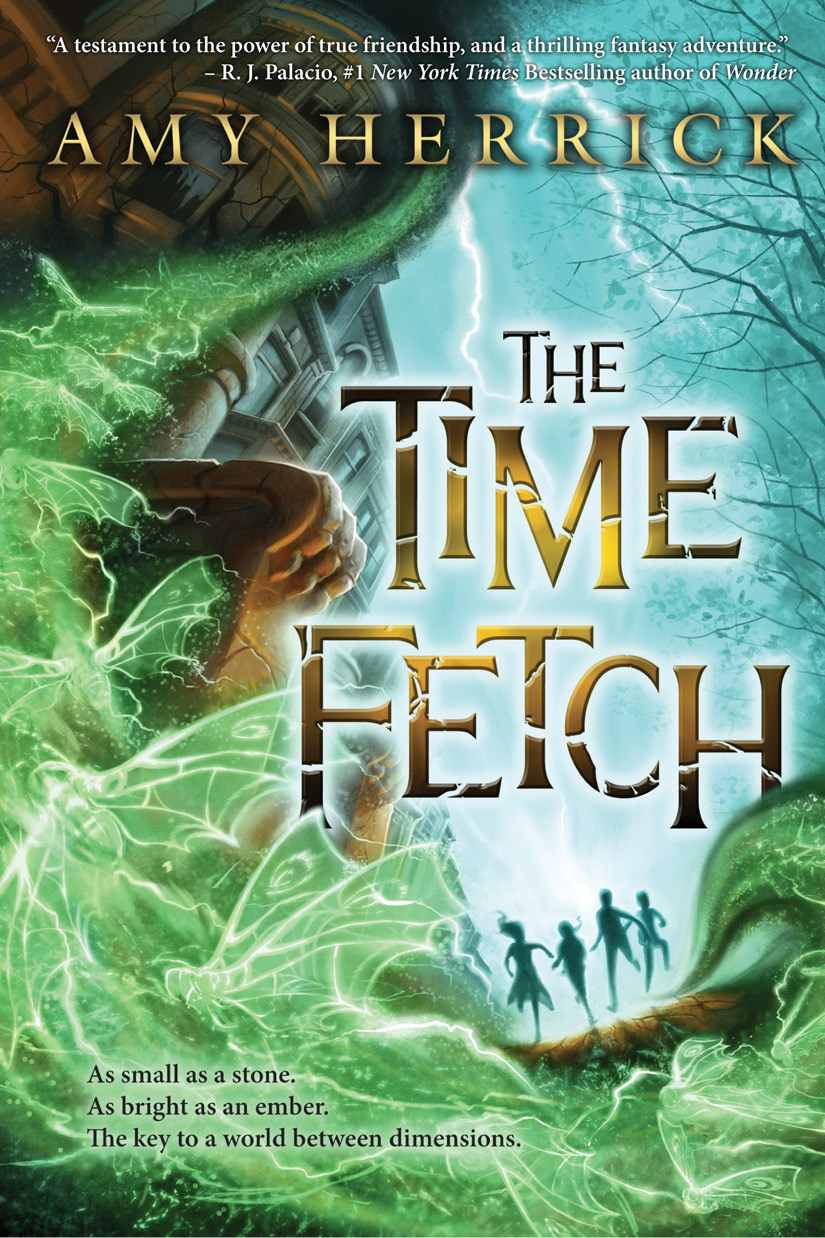

The Time Fetch

Authors: Amy Herrick

THE

TIME

FETCH

Amy Herrick

ALGONQUIN YOUNG READERS • 2013

To my mother, who found the world to be full of good hearts and useful things, and who always had enough time.

Contents

CHAPTER ONE | The Short End of the Year

CHAPTER THREE | Edward Loses It

CHAPTER FIVE | The Gingerbread House

CHAPTER EIGHT | The Song and the Spider

CHAPTER TWELVE | The Disappearing Pumpkin

CHAPTER FOURTEEN | Time Eaters

CHAPTER FIFTEEN | The Green Man

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN | The Cat Gate

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN | Hot Chocolate

CHAPTER TWENTY | The Calling In

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE | The Doorway

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO | Aunt Kit’s Party

The Fetch

First there was the doorway. It appeared high up in the back of a midsummer night. Round as a hoop, the rim glowing faintly, it stayed open only long enough to allow the Fetch to pass through. Then it was gone.

The Fetch itself was not made of anything you could hold in your hand, but was tiny and bright as a single ash blown out of a bonfire. It irritated and offended the darkness and the darkness began to coat it in a smooth pearly casing the way an oyster does when a grain of sand gets into its shell. This hardly solved the problem, for as the thing grew bigger it began to hum excitedly.

In annoyance, the night spat it out.

It shot across the sky in a swift arc. Unless you knew what you were looking for, you would have mistaken it for a shooting star. Its pearly shell was translucent. Its insides shone out a bloody gold, the color of your hand when you hold a flashlight against it in a dark room. The humming grew louder. Inside the Fetch, the Queen and her foragers had begun to awaken.

As they fell down from the cold glory of stars into the trembling air, the Queen sang out invitingly.

A hungry and half-cracked old owl heard the thing passing by. He plucked it out of the air. In his mouth, the warm Fetch took a nutlike shape. The owl perched on a branch and tried to open it with his beak, but to no avail. The thing was much too hard. The bird whacked the shimmering shell against the branch, but that didn’t work either. At last, extremely frustrated, but too hungry to give it up, the owl swallowed the thing whole and flew off. The Fetch, of course, was indigestible and burned the owl’s stomach. Restlessly, the bird flew over field and town and forest. For reasons he did not understand, he found himself heading toward the great city where he had been born. When he landed, at last, in the high branches of an oak in a small city garden, he tried to make himself comfortable. But he was miserable all night long.

At last toward morning, he passed the wretched thing, covering it in an excellent camouflage of green excrement.

Down it plummeted, humming with excitement, and landed in a tangled bed of ivy.

The owl, tremendously relieved, flew off to his destination feeling better than he had felt since he was a nestling.

Morning came. Inside the Fetch, the foragers and their Queen were wide awake and hungry.

The months that followed were rich and golden, and the Fetch was well hidden. The foragers were bound tightly to their Queen’s authority. The Queen was an old one and knew full well that, left to their own devices, the foragers would eat until nothing remained. But as she commanded, they took only what was leftover or would not be noticed. This was plenty. The varieties of time are endless in a city in the summer. There was every kind of rhythm and heartbeat, from the quick and spicy, to the slow and sweet. So many different kinds of minutes going by, and who would notice a missing one here or there?

But all too soon, the days shortened and the air grew colder. The Queen sensed her own hour drawing close and she knew the law. Her final task must be completed soon. She shook out her green-charged wings and settled herself for the work ahead. She began to sing. The song she sang was an old one, and its notes could travel great heights and distances. She sang for three days and three nights, pausing neither to eat nor drink. Her foragers heard and came flying drunkenly home. By the time the last one was nestled in, the Queen’s strength was almost spent. Still, she continued to sing until all were asleep. Then, at last, she came to the end. With the final note, her tiny heart burst open in a shower of sparks. A moment later, she was gone.

The Fetch, full of treasure, sealed itself shut. All that remained was the wait for the Keeper to open the doorway and call it back. Meanwhile, the Fetch was camouflaged in a shell of such commonplace dullness, none else could possibly be interested in it.

Part One

CHAPTER ONE

The Short End of the Year

On a Wednesday night toward the middle of December, the temperature dropped twenty degrees within a few hours. A wind came wolf-howling through the streets. Garbage cans were knocked over and tree branches splintered and snapped to the ground.

Edward slept through it all until the early morning, when he became aware of an incredible racket. It sounded like all the church bells in Brooklyn had gone crazy. But when he sat up, his heart pounding, he realized that it was just his aunt’s windchimes jangling away out in her precious garden.

A cold and unmotivating dawn was just now beginning to break in at his window. He saw from the clock that it was a little after seven. He reminded himself that it was all dancing atoms. Nothing was solid.

Pulling the blankets over his head, he caught the tail end of a dream, something about an unfinished homework assignment. It slid by him like a snake into the woods, but the frantic windchimes clanged and clamored as if they were trying to give some sort of warning. Edward, who took his sleeping very seriously, tried to ignore them, but then he remembered. The rock. He was supposed to bring a rock to science class. Mr. Ross had given them two weeks to find a glacial moraine somewhere in New York City and bring back a rock from it.

Edward preferred to wait till the last minute to complete homework assignments. The last minute had arrived.

There must be a rock or two out in his aunt’s little garden.

“Edward!”

The voice was surely addressing some other Edward.

“Edward, take that blanket off your head.”

He pulled the blanket more tightly around himself.

“Taste the air!”

Taste the air? She was a certified fruit loop.

“It will make it easier to wake up. Taste the air.”

He didn’t want to wake up. He wanted to stay in this warm soft place at least until late spring or early summer.

“You’re going to be late for school.”

What kind of twisted, criminal mind had come up with this idea of school before noon?

Through the blanket he smelled something. There was a strong burning smell, but then something else brushed lightly against the inside of his nose—something powdery and sweet. It took him a moment to remember. He slid the blanket off his face just enough to be able to stick his tongue in the air. He thought he could taste it—a very, very faint trace of confectioner’s sugar melting on his tongue.

Pfeffernusse. The little cinnamon-and-honey-flavored cookies his aunt always made at the start of the winter season. It was an illusion, of course, like everything else. Just little odor molecules firing off the neurons in his nose and then evaporating.

It was an illusion almost worth getting up for, but not quite. He snuggled back down.

There was a loud knock and the door flew open with a bang.

He heard her feet making a pathway through the treacherous swamp of dirty clothing and books and debris that covered the floor of his room. He felt her settle herself on the foot of his bed with a little

umph.

“Why don’t you just come on in?” he muttered. “Why don’t you just come in and make yourself comfy?”

“Edward, there’s no time to pussyfoot around here. I have received a warning. The first batch of pfeffernusse caught on fire. That is something that has not happened to me in over ten years and when that occurred . . . well, it was a very close call. I think it would be prudent to prepare the house now. I want you to come straight home today. We’ll start hanging the evergreens and putting the lights in the windows. The sooner the better. We don’t want to wait till the last minute. Time doesn’t grow on trees.”

“That’s money,” he muttered from inside his little nest.

“What?”

“Money. Money doesn’t grow on trees.”

“Yes, but money is piffle. And time is one of the great treasures.”

If he asked her to explain herself, it would encourage her. He never encouraged her.

“Do you know why it is one of the great treasures?”

He didn’t make a peep.

“Because without time everything would happen at once.”

Whooooaaa.

He always wondered where she got this stuff from.

“If everything happened at once,” she continued, “there would be only darkness and chaos. Don’t you wonder what the world would look like without it?”

Uh—no.

“Time is the One who gives birth to order, the One who makes the weaving of the Great Web possible.”

No, no. Not the Great Web. Not this early in the morning.

The windchimes continued their demented clinking and clanging.

She paused and then, as was her way, she abruptly changed the subject. “Now, I have a wonderful idea,” she said brightly. “Why don’t you bring someone home from school today to give us a hand? There’s lots of extra pfeffernusse. The second batch came out fine.”

She was so obvious, he sometimes felt sorry for her. She wanted him to care about his state of lonely geekhood.

But he didn’t. He was very close to perfecting his cloak of invisibility. Soon he would be able to walk straight across the school lunchroom without anyone seeing him, or snooze through an entire class without the teacher noticing a thing.

“Maybe you could invite that girl next door. She’s in some of your classes, isn’t she? She always seems so nice and . . . perky.”

Edward snorted. Perky as a Cuisinart on high speed. About the very last thing he needed was Feenix sitting in his aunt’s kitchen eating pfeffernusse.

“Was that a snort?” Aunt Kit asked. “Are you ready to emerge? I do hope so. Because it’s getting late and if you don’t start moving soon, I shall have to lift up the blanket and let this quite large spider go on your leg.”

He took the blanket off his face and stared at her.

He thought about how it was hard to really see people you’ve been living with for a long time. He’d been living with her since before he could remember. She’d adopted him when his mother died. He’d been three. The only memory he had of his mother was her voice singing him to sleep. Sometimes, just as he was drifting off, he heard her again. But that was it. His father had apparently never been in the picture. All he’d been left with in the way of family was his aunt. Lately, he’d been feeling that she was way more than enough. When he tried to imagine what it would be like to have two parents and maybe even a brother or a sister, his mind boggled. Other people were such major energy suckers. He stared at her. Possibly others might regard her as not bad looking. He couldn’t tell. He’d been looking at her for too many years. He warned himself not to make the mistake of thinking she was harmless. He’d made this error many times.

In her lap was a small plastic container with a lid on it. He looked at it uneasily. “What’s that?”

“I told you. A spider. I saw it climbing up the outside of the bathroom window. I imagine it was trying to get warm, so I brought it inside. I’m going to let it make a little place for itself in my herb pots.”

She grew oregano and parsley and thyme on the windowsill over the kitchen sink.

“Or I could let it go on your leg.”

He sat up, keeping his eye on the container. “Do you think you might get up off my bed and remove yourself from this room? I have to dress.”

“Good.” She rose, holding the container in her hands. But then she didn’t move. “I realize that what I’m about to say is probably a waste of perfectly good breath, but I want you to be careful. It’s the short end of the year. The curtain between here and there grows thin. It would be much better if you didn’t travel alone. Isn’t there anyone you could walk to school with?”

He stared at her. “You think I’m gonna get mugged because it’s almost the winter solstice?” She had a bee up her butt about the solstices.

She made a little

tcching

sound of impatience. “There are always dangerously powerful forces abroad when the shortest day draws near, but this time, I sense, one of those really loaded moments is going to arrive. A sneeze at one end of the world may change the whole course of things to come. At least do me a favor and try to stay awake. And probably best to stay away from the park for now. Too many ancient things astir in there.”

He laughed at her. He hadn’t gone walking in Prospect Park since back in the day when he used to play tee ball.

“And make sure you wear your winter jacket. It’s hanging on the coatrack.”

When she was gone, he lay down again and sighed. He couldn’t have fallen back asleep if he’d wanted to. He wondered what she was going on about this time. The wind chimes tinkled and clanged away. With a start, he remembered the rock for science class. He would have to hurry.

By the time he got down to the kitchen, she was gone. She taught a pastry class in the city several mornings a week. He sat down on one of the tall stools and slowly ate a half dozen of the little confectioner sugar–coated cookie mounds at the counter. He had to admit, if nothing was really real, eating, at least, seemed sometimes worth the effort. He was about to take another when his aunt’s cuckoo clock made its little whirring noise and then sounded the half hour. Edward rose with a sigh and took a deep breath. He opened the kitchen door, which led to her little garden, and stepped outside.

The wind nearly knocked him over. It had turned bitter cold.

Hurriedly, he poked around in the herb beds. Nothing. Not a rock in sight. The squirrels must have eaten them all.

He pushed at the rose bush and pricked himself on a thorn. Nothing there either. He sucked his thumb angrily. Why did everything have to be such a hassle? Was it so much to ask for, just one little glacial moraine rock?

In the western corner of the garden was an old oak tree. Its branches were whipping back and forth in the wind. Edward trotted along the brick path and stopped at the base of the tree. There were acorn shells and crunchy old brown leaves everywhere and a tangle of dying ivy. He kicked his way through this mess until his foot encountered something hard.

He bent to examine his find.

Hallelujah. A rock.

The windchimes jangled frantically.

The rock looked like a perfectly ordinary rock, rough and greenish gray. He reached out and grabbed hold of it. To his annoyance it didn’t come free. It must have been partly buried. He scrabbled around it with his fingers and gave another heave. Again, the stupid thing resisted. This time he found a stick and jabbed it into the ground beneath the rock. A sharp sensation, like an electrical shock, went through his arm.

Now, he was ticked off. He dropped the stick and grabbed the stone with both hands and heaved mightily. This turned out not to be necessary. Like it was playing with him, the stone now seemed to fly up into his hand. He fell backward, with a

plunk,

onto his butt.

“Very funny,” he said. The stone felt oddly warm in his hands. Weird. He stuck it in his pocket and went inside. He hoped it was the sort of thing you could find at a glacial moraine.

From behind the curtain, he saw Feenix come out of her house and go striding down the street in her cowboy boots and long black coat. The coat was open and flapped behind her. She tossed her black mane of hair as if she imagined cameras going off all around her. Her many earrings flashed once in the morning light and then she turned the corner and was gone.

Feenix. How could her parents have been so lame as to name her something like that?

Not that he couldn’t handle her. Not that he couldn’t use his mind’s eye to turn her into a harmless mass of positive and negative electrical charges, but he waited a few careful minutes and then stepped out into the morning.

He moved slowly, keeping his head down and his shoulders hunched. Because he did not believe in exercise, Edward did not generally walk to school. But he knew that Feenix would take the bus on a day like this, so he figured he was safer staying on foot. The school was an entire seven blocks away, but in this case, it was worth the tremendous effort.

The street was busy as always at this time of morning, people emerging from the coffee shop, gingerly holding their steamy four-dollar caramel macchiatos out in front of themselves like little bombs that might go off at any second. They hurried along to the subway, trying not to blow themselves up. Little whiny kids got pushed in strollers to their daycares or wherever. Here and there, among the crowd were other prisoners of the state like him, heading toward their six-hour dates with unrelenting boredom. You could recognize them easily from the way they tried to keep their faces really blank and unreadable. He supposed he probably looked the same.

There were actually little patches of ice here and there on the ground. In spite of himself, he was glad his aunt had made him wear the jacket.

The sky was gray and low, and the wind blew in little bursts.

Red and green plastic holiday decorations hung from wires strung over the street. They swung wildly. The store windows, still mostly locked behind steel gates at this time of the morning, were fully loaded with Christmas trees and electric menorahs and smiling snowmen.

Edward paid very little attention to the holiday stuff. As a kid, he’d gone along with all of his aunt’s crazy winter solstice celebrations—the baking, the decorating, the singing, the big party, but now he no longer believed in it.

As a general rule, Edward didn’t believe in anything. That is, he’d come to understand that reality was largely a hoax. One of the many useful things that Mr. Ross had taught them was that everything was made of atoms, and atoms were mostly empty space. Everything might appear solid. But it wasn’t. It was 99 percent empty space.

When you took for granted that the floor you were standing on was solid, you were making a big mistake. When you put your butt down on a chair and didn’t go through the chair and the chair didn’t go through you, it was because of the magnetic repulsion of electrons against each other. You were really floating a minuscule fraction of an inch over the surface of the chair. If it weren’t for that force of repulsion, everything would just pass right through everything else.