The Time of Our Lives (15 page)

Read The Time of Our Lives Online

Authors: Tom Brokaw

At the time he bought it, Elvis was a huge star, the biggest recording artist on the planet, well on his way to becoming the legend that lives on. He bought Graceland for $102,500, and that included almost fourteen acres of land.

The terms? The king paid $10,000 down in cash, plus another $55,000 he received from the sale of the house his parents were living in. He took out a $35,700 mortgage for the balance, payable over twenty-five years.

This kind of proportionate house pricing went on for another twenty years.

THE PRESENT

When it came time for our three children to find homes, they were at the wrong end of the great American real estate boom and living in two of the priciest cities in the country, New York and San Francisco. With our help, they each bought comfortable but not luxurious homes for prices that were, as I liked to remind them (not entirely in jest), what I once had hoped to earn in a lifetime of labor.

The big jump in housing prices has not been confined to big cities. Nationally, the median price of a new single-family home went from just over $160,000 in 1999 to $248,000 in 2007, a jump of more than 50 percent. The sale prices of existing homes went up close to 60 percent during that period.

It was a booming bubble until it wasn’t, and then the landscape was littered with foreclosures, abandoned homes, unfinished developments, and failed lending institutions.

Owning a home and paying the mortgage that comes with it went from being the American Dream to worse than a nightmare for many families. Nightmares go away, but the consequences of owning a home worth less than you paid for it—foreclosure and credit difficulties—linger for a long while.

Our youngest daughter, Sarah, is not married and has no children, so the housing and economic strain on her is not as great, for now. But she’s watched her sisters, and she knows the financial pressures that come with a family these days. As our San Francisco daughter, Jennifer, laments from time to time, she and her husband are both highly trained physicians in thriving practices but their finances are constantly strained by the cost of housing and education for their children. They turned to the private school option only after their daughters, Claire and Meredith, didn’t win a place in the San Francisco public school lottery. They hope that San Francisco’s public education standards will not wither under the strain of the city’s and state’s fiscal pressures.

Our New York daughter, Andrea, her husband, Charles, and their two daughters have an identical dilemma with the cost of housing and education. He’s a Yale graduate with a law degree from the University of Chicago who has held senior positions in the Clinton administration Justice Department and the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services. She has a senior management position at Warner Music.

They live in his old neighborhood, a collection of vintage apartments on the Upper West Side of New York. Not so long ago a couple with their résumés and earning power could have easily bought one of the apartments with their salaries. Now, as my daughter says, with a kind of morbid laugh, “Dad, I need to cash in before you check out.”

This is not what our daughters expected when they left home to study at good universities. They had grown up in comfortable circumstances but always with the reminder of their grandparents’ prudent lifestyle and constant admonitions from their parents that they were not trust-fund kids, inoculated against finding a working profession and pursuing it.

It is not that Meredith and I and our daughters are whining about all this. “Astonished” is a more apt description: astonished and concerned for those of their generation who aren’t able to fill the gaps between income and the fundamentals.

This is, or should be, a lesson for our time—for all of us—whatever our financial status. Shannon Oliver and her family were typical of what was going on.

I met them while crossing the country on U.S. Highway 50, reporting on the American character for USA, the cable channel. The Olivers personified the distressed population in Fernley, Nevada, a shake and bake suburb of Reno with rows of houses in new developments with names such as Ponderosa, Green Valley Estates, Autumn Glen, and Rawhide. If it was not the foreclosure capital of America, it was a contender.

Shannon was fighting to save their home, a modest modular house they had purchased in 2005 for $187,000, at a time when her construction worker husband Troy was making close to a hundred thousand a year in the building boom of northern Nevada.

They had moved from California to Nevada to find the good life and, as Shannon put it, “get the American Dream—our own home.” But they wanted more, and why not? Didn’t everyone they saw on their street or on television have more? So they bought two new cars as well. Shannon’s eyes sparkle as she says, “I loved my little Jeep Liberty.”

Making ends meet was a stretch but when Troy came home with extra pay from working overtime, it was reason enough to splurge on dinner and a movie out. Saving the overtime pay didn’t occur to the Olivers.

Then it all came apart. The building boom went bust and Troy lost his job, and then another. Shannon drove a school bus but her salary was not nearly enough to keep up with their obligations. The cars were repossessed. The value of their home went into free fall, dropping to $60,000, in a neighborhood of foreclosures and desertions by others in similar straits. The Olivers’ home was a modular unit, and today it is hard to imagine it ever had the real value of the original purchase price.

When we met in the fall of 2009, the Olivers’ every waking moment was consumed by trying to find a way to save their home and what little was left of their dream. Shannon was reading everything she could find about government mortgage help programs and talking to her bank contacts, explaining that they could pay $950 on their mortgage but not the $1,500 called for in the contract.

Nothing worked. They simply had far too much debt and were eventually forced to declare personal bankruptcy. Even if they had been able to make a deal with the bank, their burden would not have been eased. A year later, a matching modular home in the same neighborhood was on the market for $49,000. By November 2010, Fernley, a community of just under 13,000 residents, had 530 homes in foreclosure, and prices continued to drop.

Still, Shannon, ever the optimist, saw a bright side. “We’re spending more time together as a family,” she said. Entertainment now is watching their son, Jayce, play football, or renting DVDs for a dollar a night.

“We’ve learned a very hard lesson,” Shannon said. “We as a nation were living much too hard, much too big. We have to get back to basics.”

Jayce often asks why they can’t have the things they did before and Shannon has been patient in explaining the realities of their new economic condition. He’s a serious nine-year-old and there’s been little whining. When Jayce gets to his parents’ age, how will he manage his finances after this searing experience of his childhood?

Shannon and Troy Oliver in the home they lost

(Photo Credit 8.1)

Perhaps he will be more mindful of saving before spending. There is no doubt he is getting an up-close look at the importance of education in developing job skills that improve your chances of working even when a recession comes along.

THE PROMISE

Marketing and retail research organizations are doing extensive work with young consumers to determine their current and future buying habits. One company, GTR Consulting, has already come up with a new name for them: neo-frugalists. The Food Institute commissioned a study on teenage eating habits during the recent economic difficulties and discovered there was a 20 percent drop in dining out for the younger set between the fall of 2007 and 2009.

A friend of mine, Doug Tompkins, had a turnaround moment in his life. With his former wife, Susie, he founded Esprit, the hip clothing company of the eighties and nineties. They became wealthy and bought a stunning home just off Lombard Street in San Francisco, which they filled with masterpieces from the Colombian artist Fernando Botero.

But then Doug, a world-class kayaker, rock climber, and deeply committed environmentalist, hit a philosophical conundrum: How could he be true to his environmental values and still push more clothing on consumers—more clothing than anyone could need?

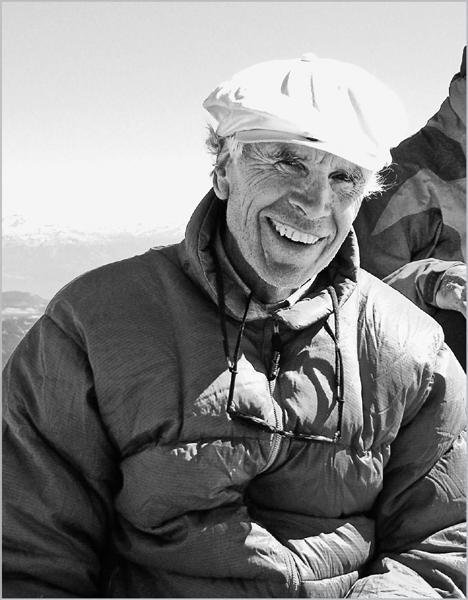

Doug Tompkins, founder of The North Face and Esprit, a world-class outdoorsman and dedicated environmental philanthropist

(Photo Credit 8.2)

“I asked my mom,” he said, “how many shirts Dad had during the forties, and how many dresses she had. She said, ‘Oh, I don’t know—just a few.’ That got me to thinking. ‘Why do we need more now?’ ”

So Doug sold his interest in Esprit, sold much of his art, and moved to South America where he began buying up hundreds of thousands of acres in Chile and Argentina, converting them to wilderness parks or running them as sustainable ranches. As rich as he was at Esprit, he’s even richer now, personally and financially.

Kevin and Joan Salwen of Atlanta have gotten a good deal of attention for a do-over of their lives prompted by a question from their daughter, Hannah. They were at a stoplight when Hannah noticed a homeless man with a sign saying he was hungry. There was a Mercedes at the same light, and Hannah said, “If that man had a less nice car, that [other] man could have a meal.”

When the Salwens got to their two-million-dollar home in an upscale Atlanta neighborhood, the conversation continued about “How much is too much?” Hannah and her brother, Joseph, made it clear they didn’t need all the things their parents’ financial success could afford.

Kevin had been a

Wall Street Journal

reporter before becoming a successful entrepreneur and Joan was an executive at Accenture, the financial services firm, before returning to teaching, something she loved more.

The family dialogue didn’t let up, and the Salwens came to a consensus: Let’s sell this big house and give half to charity. The half amounted to $885,000 net.

They performed a diligent search of where they wanted the money to go and decided to spread it throughout twenty villages in Ghana. That, in turn, led to a widely praised book,

The Power of Half: One Family’s Decision to Stop Taking and Start Giving Back

, addressing what well-off families can do with half their home values or, carried to the extreme, their net worth.

As Kevin puts it, “Now we always look at our lives and the other halves we can do. We’re always going to be involved.”

Obviously, Tompkins and the Salwens are exceptions, even at the high end of the personal wealth scale.

The rest of us can be be inspired by their model, however, and pause to reflect on the large posters now adorning the lobbies of JPMorgan Chase, the nation’s most successful large bank. They feature self-confident young men and women with the banner headline

SAVE IS THE NEW SPEND

.

Save for a smaller, more affordable home, perhaps. Obviously, the long-running trends have come to a halt. The average size of an American house expanded by 140 percent between 1950 and 2007, from just under 1,000 square feet to more than 2,400 square feet. That’s twice the average size of homes in France and Germany.

Already, there are signs of a reversal.

The Wall Street Journal

profiled an Atlanta company, John Wieland Homes and Neighborhoods, that was known for building trophy homes throughout the Southeast selling for an average of $650,000 apiece. Just a few years ago, they had Jacuzzis, butlers’ pantries, vaulted ceilings over breakfast nooks, and laundry rooms as large as bedrooms. Now Wieland is building homes without fireplaces and substituting fiberglass tubs for the pricier tiled models.

One of Wieland’s new homeowners spoke for many when he said, “There’s a lot more that comes with those McMansions. There’s a lot more cleaning, a lot more heating, a lot more cooling.” There’s also a lot more debt.

Opportunities could grow out of this dislocation between finances and fundamentals. For example, smaller, more energy-efficient homes in communities or developments with more green space could take the place of that third stall in a three-car garage. Urban dwellers seem to get along fine by sharing a common wall with a neighbor in an apartment. Why can’t a new generation of suburbanites look to more townhouse construction with the saved energy costs of common walls and wider common green spaces in the neighborhood?