The Train to Warsaw

Read The Train to Warsaw Online

Authors: Gwen Edelman

THE TRAIN

TO WARSAW

THE TRAIN

TO WARSAW

A Novel

Gwen Edelman

Grove Press

New York

Copyright © 2014 Gwen Edelman

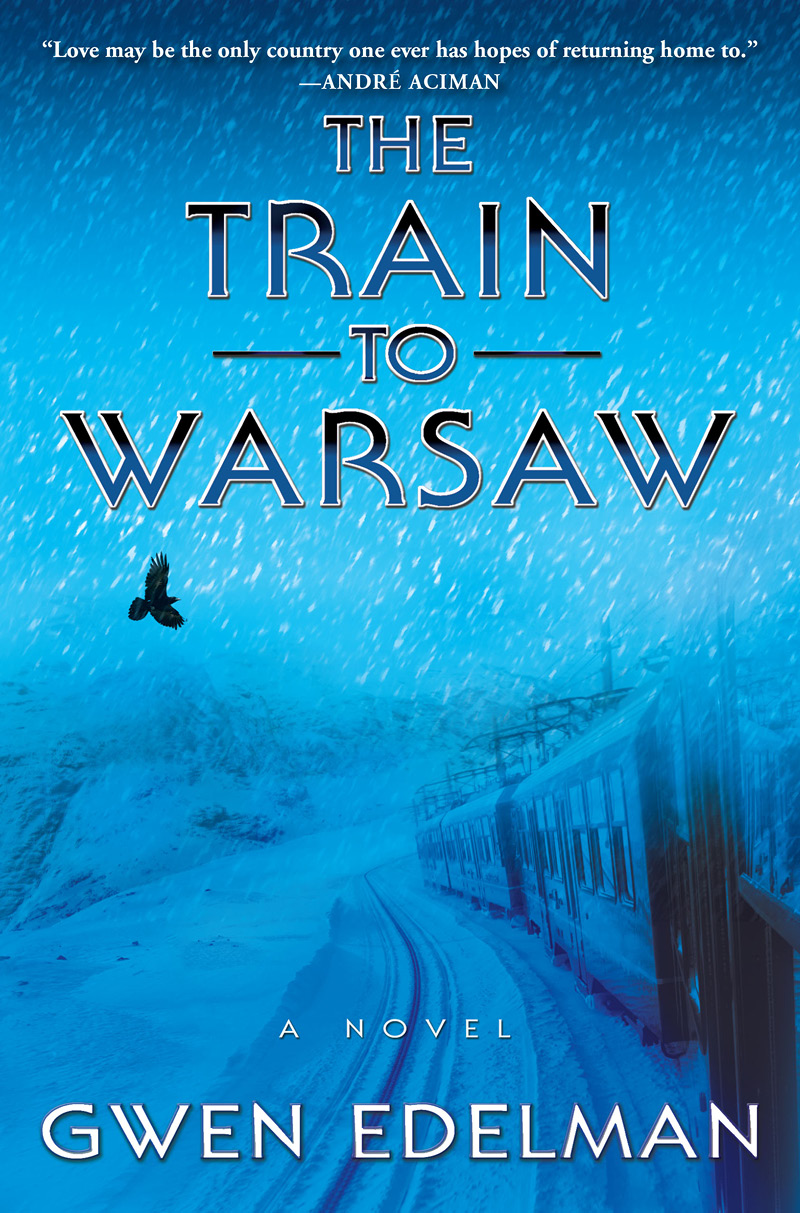

Jacket design by Royce M. Becker

Jacket photograph © Robert Harding Images/Masterfile

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced

in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means,

including information storage and retrieval systems,

without permission in writing from the publisher,

except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book

or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher

is prohibited. Please purchase only authorÂized electronic editions,

and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy

of copyÂrighted materials. Your support of the author's rights

is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions

wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom

use, or anthology, should send inquiries to

Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011

or

[email protected]

.

Printed in the United States of America

Published simultaneously in Canada

ISBN: 978-0-8021-2244-5

eBook ISBN: 978-0-8021-9264-6

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

For

Jakov Lind

THE TRAIN

TO WARSAW

The train to Warsaw traveled into the snowy landscape. The sky hung white and motionless above the earth and a pale thin light shone on the snow. Once in a while the bare branches of a tree became visible beneath the snow. And once they saw a bird with black wings as he perched on a snowy limb.

She sat wrapped in a heavy coat, a fur hat pulled over her hair, staring out at the snow covered ï¬elds rushing past. Look, she said, pointing a gloved ï¬nger, there's a bird who has forgotten to ï¬y south. He sat opposite her in the closed compartment, smoking his black tobacco. He wore a thick scarf wrapped around his neck. His wavy white hair rose up off his forehead like a prophet. Just like the Jews, he remarked. They didn't ï¬y off when they still could. He pulled a ï¬ake of tobacco from his tongue. And then it was too late. They should have learned from the birds. Were we any better? she asked. We did what we could, he replied.

He pulled back the stiff pleated curtain that hung from the window and his dark eyes peered out. This frozen landscape makes me melancholy, he said. There is nothing human in it. She stared out, her head tilted as though listening. I did not think, she said, that I would see this landscape again. This endless snow. How beautiful it is. The whole world white and unbroken.

She rubbed with a gloved ï¬nger at the condensation. Everything is frozen. I remember that. And that pale light. We wore fur lined boots, and doeskin gloves. And went sledding in the Saxony Gardens. When you still could, he remarked. Please, Jascha, don't ruin it for me. Ruin it for you? he asked. Wasn't it the ÂOthers who did that? She stared out the window. In all this whiteness, I can't tell where the sky ends and the earth begins, she said.

He ï¬ddled with the small metal ashtray, attempting to pull it out. Are we a race of birds, he asked, that we are expected to use these tiny ashtrays? He frowned and his lips tightened as he tugged at it. It's going to come out, she warned him. But he continued to pull angrily and suddenly the ashtray tore loose from the wall below the window, scattering tobacco and ashes. She shook her head. You haven't changed. It serves them right if I grind my cigarettes out on the ï¬oor, he said, and his face took on a reckless expression. She leaned over to pick up the ashtray and reinsert it. Still as stubborn and impatient, she remarked, as you were Back There.

Now as they sat together in the freezing compartment, he said to her: I'm very angry with you. Did I not tell you I wouldn't go back? But you nagged me and nagged me. He pulled up the collar of his coat. Don't they heat these trains? he asked irritably. Do you by any chance remember the Garden of Eden? How Eve nagged him night and day until at last he ate of the fruit. And we know what happened then. We have long ago left the Garden of Eden, she replied. It's our last chance, she said. If we don't go back now, we never will. Why go back at all? he wanted to know. Didn't we have enough of it Back There?

Out the window the wind shook the pine trees and the snow spun off in powdered waves. Look how slender the birches are, she said to him. They look as though they would crack beneath the weight of the snow, but they don't. God made the birches in Poland to withstand everything, he told her. He knew a birch in Poland would not have it easy. Lilka gazed out the window. There wasn't a bird or a leaf, she said. If there were we would have eaten it. All the trees and all the birds had ï¬ed to The Other Side. And inside there was us. Shut up behind high walls. And it seemed as though all of life was on The Other Side. I dreamed of trees and birds, then and later. They appear to me in all shapes and forms, and often they speak to me in a language I seem to understand. But then the leaves drop off one by one and all that is left are bare branches. She shrugged. Polish winter.

They smoked silently. Nearly forty years have passed, she said at last. She removed her fur hat and ran her ï¬ngers through her blonde hair. He ground out his cigarette. You still “look good” as we used to say Back There, he remarked. You still look Polish. Where did you get those blue eyes and ï¬axen hair? Did your grandmother lie down with a Ukrainian peasant in the heat of the day? She sighed. You've asked me that a hundred times. Have I? He laughed. Give me your hand, darling. Let me kiss it.

The seats were of worn maroon plush and the small white antimacassars on the backs were yellowed with age. When they shifted in their seats the springs cried out. The stiff curtain at the window rocked with the movement of the train. Lilka reached into her purse. She pulled out a lipstick and a small mirror and carefully applied red lipstick. After the war, she said, I found a red lipstick someone had left on a train seat. I wiped it off and put on the lipstick. My lips were gleaming red. When I looked at myself I thought how cheerful I looked, how festive. And I thought that if I wore it all the time, they wouldn't notice how thin my face had become. My bones stuck out then and my cheeks were hollow. Women who were not born then try to look like that. She shook her head. They understand nothing. Well never mind, she said and put away the lipstick.

The faces of the starving became like masks, he said. He ground out his cigarette and lit another. She drew off her gloves and lit a cigarette. Please, Jascha, she said with a frown. Don't frown, darling, he said. It makes you look older.

The compartment grew heavy with smoke. The white light from outside turned the rising whorls bluish and a haze fell over them. When we get to Warsaw, said Lilka, I want to walk in the Saxony Gardens. The swans won't be there in this cold, but even so . . . She grew animated. My parents used to take me to the Saxony Gardens every Sunday. My father would put me on his lap after we had fed bread to the swans and imitate the sounds of animals. A cat, a mouse, a cow, a duck. There was your father, my mother told me, squeaking and quacking and mooing. I told him he would scare youâyou were so small. But it made you laugh. Lilka's cheeks grew shiny. He used to let me watch him shave. I was three or four. And he would dip his ï¬nger into his shaving cup and put a little dab on my nose and sing me a little song. Today I bake, tomorrow I brew, and Rumpelstiltskin is my name . . .

I know about Rumpelstiltskin, said Jascha. He didn't want anyone to guess his real name. Just like the Jews. But one day in the forest he pronounced his name out loud and that was the end of everything. He blew smoke rings into the air. Just like the Jews.

In the Saxony Gardens, he said, I used to watch couples coupling in the shadows cast by the bushes. Once when I came too close, drawn by the patch of glistening pink skin where the girl's skirt had ridden up, he shouted at me to get lost. The girl raised her head for a moment and laughed. He's a child, she said. He wants to learn. Let him learn somewhere else, said the man, and he pulled at her skirt. But in a moment he had forgotten me and was pumping away.

Is that how you learned what it was all about? Not at all, he replied. I tore the relevant pages from my parents' medical encyclopedia and took them to school. There I charged money to let the other boys have a look. It was clinical, but informative. My parents never missed them. It seems they did not consult those particular pages. I had them with me until I left home. By then I was tired of them. How often could I study anatomical drawings of the sex organs? Besides, by then I had seen the real thing. He dropped his cigarette on the ï¬oor.

No Jew could set foot in the Saxony Gardens, said Jascha, don't you remember? Or in any other gardens. She looked at him. Why do you tell me this now? she asked. Was I not there? Ach, Jascha, you want to ruin it for me. Is that how you see it? he asked. London is not my home, she said.

Even after forty years, London is as alien to me as the other side of the moon. The sky is alien to me. The streets, the houses, the landscape, the food, the voices. And most of all, the faces . . .

Jascha, she pleaded, I want to go home. He shook his head. My poor darling, he said. Do you think that going back will take you home again? He reached forward and took her hand in his. Lilka my angel, he said, let us eat chocolates and forget all this. Give me the one with the cherry liqueur, he said and held out his hand. And what if that is the one I want? she asked coquettishly, shaking out her hair. Light me another cigarette, she said. One of mine. I don't want your dreadful Russian ones. I like them, he said. They remind me of

mahorka,

that foul black tobacco the Russians brought at the end of the war. He took out one of her English cigarettes and lit it for her. Black as night and dense as pitch. But I got used to the taste. And now I can't do without it.

The train ï¬ew through the snow, throwing up snowy spray as it went, scattering the wildlife that came near and ï¬ew or hopped or ran from the oncoming train. On what day did God create snow? asked Jascha, looking out the window. On the same day He created Poland, replied Lilka. He leaned forward and touched her cheek. What a sweetheart you are, he said.

He drew out a dented and tarnished silver ï¬ask from his pocket. Where did that come from? she asked. He smiled. I found it in one of my snow boots, which I haven't used since the last time it snowed in London, a hundred years ago. Let me see, she said, reaching out a hand. First let me drink, darling. He took a long drink and offered it to her. She stared at it. Jascha, this is from Back There.

I found it in an empty apartment, he said. They weren't coming back. Why shouldn't I have it? Instead of the Germans or the Ukrainians. I had it with me all the time. I began to feel it was keeping me alive. What was in it, you mean, she said. No, he replied. The little ï¬ask itself. She held it gingerly and gave it back. It's strange to see it after all this time. An artifact from another lifetime. He looked at her. That's what I've been trying to tell you, darling. Another lifetime. You won't ï¬nd your way back. God knows why we're going, he added. Didn't we have enough?

Jascha stared out the window. When Dante was exiled, he said, what he missed more than anything was the taste of his own bread. Tuscan bread had no salt. For Dante, the bread of exile was unbearably salty. How unhappy he was. Jascha handed her the ï¬ask. Have a sip, darling. Have two. Do you think you are the only one who dreams of home?

She took the ï¬ask and drank. The waters of forgetting, she said, wiping her mouth with a white lace handkerchief. He smiled. Look at you. Where did you get those manners? Like a Polish countess.

It's freezing in here, she said. Can't they heat these trains? Look, she said and pointed to the steamy breath that rose up before her face. It will be worse when we pass the Polish border, he said. The temperature will drop and there will be icicles in our hair. Let me sit beside you, she said softly.

The light was fading, the slender birches wreathed in shadows. The compartment grew darker. I remember this, he said. The Polish darkness that comes on in winter at three in the afternoon. Our parents called to us from upstairs windows to come in, but we stayed out in the darkness playing as long as we could. There was no curfew then. And no walls. Only our stubborn parents who would not let us play all night. When we grow up, we thought, we'll be free. Ha. What did we know?

You never talk about your parents, she said. No, he said curtly. I can't.

He rolled a cigarette and blew smoke rings into the airless compartment. The smoky wreaths balanced motionless for a moment and then dissolved. It was a gray and overcast day when I came to London, he said. A choppy crossing. The gulls shrieked above the black water, the passengers were pale with seasickness. A sickly moon hung in the noontime sky as the ship drew near the wooden pier with its rotten timbers. Under my arm I carried my manuscript, written on pages of waxy butcher's paper and tied up with butcher's string. It might have encircled a ï¬ank steak, a leg, a neck. Instead I wound it around the packet of words, written in tiny script to save space.

We disembarked. There were men in faded uniforms with creased and tired faces feeding on some kind of soft roll. Everything was colorless. Where have I come to? Is this the end of my wanderings? This dismal and colorless island? I did not want to get off. I had made a mistake. I couldn't live in a place like this. Particularly without you. But you had disappeared.

Now in London the words streamed out of me. I couldn't sleep. I worked day and night. And every day I walked several miles to see whether there was a response to the little card I had put up on the bulletin

board at the International Refugee Organization. I couldn't afford a bus, and my shoes were too tight. So I took them off. I tied the laces together and hung them around my neck and walked barefoot through the streets of London. The desert of London. It was almost biblical, my search for you. Was it possible that you were no more? Let's not talk about that now, she said.

We had made a plan, he said. But you didn't come. Stop it, Jascha, she replied. It wasn't like that.