The Triangle Fire (7 page)

Authors: William Greider,Leon Stein,Michael Hirsch

“He smothered the sparks in her hair with his hands,” the

Sun

reported. He lifted her in his arms and headed back across the roof toward the Washington Place ladders. “Then he tried to carry her up the ladder to the higher roof.

“But because she was unconscious, he had to wrap long strands of her hair around his hands. Dragging her, he slowly made his way up the ladder.”

5. NINTH

They closed the portals, those our adversaries.

—

CANTO VIII

:115

On the ninth floor, the telephone that could have alerted two hundred and sixty persons to the peril boiling up beneath them stood silently on a table in the far, inside corner of the shop. At this table, Mary Leventhal distributed the bundles of cut work brought up from the cutting department on the floor below.

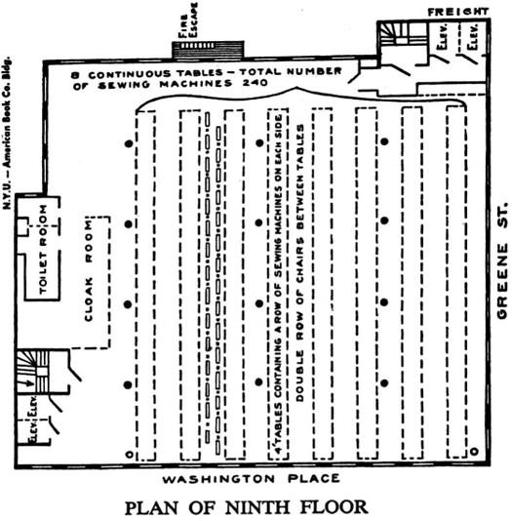

The sewing machine operators who stitched the parts together worked at 240 machines that filled almost the entire area of the ninth floor. These were arranged in sixteen parallel rows running at right angles from the Washington Place wall. Each row had fifteen machines and was 75 feet long. At their far end, the lines of machines left an aisle 15 feet wide in the space between the exit to the Greene Street freight elevators and the windows facing New York University across the back yard.

The machine heads were set into a single work table running the full 75 feet. Every two tables faced each other across a common work trough 10 inches wide and 4 inches deep which connected them. The two rows thus connected formed a plant of 30 machines, and there were eight such plants on the floor.

Under each central trough, at about 8 inches from the floor, a rotating axle, spanning the full 75 feet, drew rotary power from a motor at the Washington Place end of the plant. At that side there was no through passage from aisle to aisle. Only at the far end of the machine lines was such passage possible; all aisles between the plants led only to the passage in the rear.

Fifteen workers sat on each side of the plant, rocking in the rhythm of the work. During working hours, the horizon for each was marked by the workers facing her across the trough, one a little to the right, the other slightly to the left, and by the wicker basket on the floor to her right where she kept the bundle of work to be completed. She sat on a wooden chair; her table was of wood; her machine was well-oiled, its drippings caught and held in a wooden shell just above her knees, and the material she sewed was more combustible than paper.

Each machine head was connected by leather belts to a flywheel on the rotating axle from which it drew motive power. The machine operators bent to their work as they fed the fabric parts to the vibrating needle in front of them. Leaning forward, each seemed to be pushing the work to the machine. In turn, the rapid stitching made a rasping whirr as the operator pressed her treadle to draw power, and as if satisfied, the machine passed the work through, sending it sliding and stitched into the center trough.

At her table, pretty, blond Mary Leventhal prepared for the end of the workday by checking the book in which she kept the record of work distributed and work returned by the operators. At her elbow stood the telephone, its yawning mouthpiece mounted on a tubelike standard with the receiver hanging on a hook at the side.

Because Saturday was payday, Mary and Anna Gullo, the forelady, had just finished distributing the pay envelopes. “Mary went back to her table and I went toward the freight elevators where the button was for ringing the quitting bell. I rang the bell,” Anna Gullo said.

The machinists pulled the switches and suddenly the rasp of the machines stopped. Now the huge room filled with talk as the operators pushed back from their machines. The chairs scraped, locking back to back in the aisles and with the wicker baskets filling the long passageways to the rear of the shop.

The work week was over. Ahead was an evening of shopping or fun and a day of rest. Most of the workers good-naturedly accepted the slow progress up the aisles and around to the dressing room and the exit. Only a few impatient ones jostled ahead to be first out. Max Hochfield had learned that the way to beat the crowd was to avoid the crush in the dressing room and in the rear area of the shop. He kept his coat hanging on a nail protruding on the shop side of the Greene Street partition. When Anna Gullo reached out for the bell button, he was right beside her and out of the door as she rang the signal.

He was the first worker from the ninth floor to learn that a furnace had flamed up underneath.

When he reached the eighth floor, he could see it was all in flames. Nobody was on the stairs. He ran down another half flight and looked into the courtyard. “I saw people coming down the fire escape. I stopped. I was confused. I had never been in a fire before. I didn’t know what to do.”

Hochfield continued down the steps, then stopped: his sister Esther was still on the ninth floor. He turned to run back up. “But somebody grabbed me by the shoulder. It was a fireman. I shouted at him, ‘I have to save my sister!’ But he turned me around and ordered me, ‘Go down, if you want to stay alive!’”

This had been the first week for Max and his sister on the ninth floor. On the previous Sunday the Hochfield family had celebrated the engagement of twenty-year-old Esther by giving a party. The guests had visited until early morning, and Max and his sister stayed home the next day.

When they came to work on Tuesday, they found that their machines on the eighth floor had been assigned to two other workers. “Mr. Bernstein told us if we wanted to work we would have to go to the ninth floor. That’s how we came to be up there. Maybe if my sister wasn’t engaged she would be alive.”

The flames invaded the ninth floor with a swiftness that panicked most of the girls but paralyzed others. Pert, pretty Rose Glantz had been one of the first into the dressing room between the door to the Washington Place stairs and the windows facing the University. In high spirits she began singing a popular song, “Every Little Movement Has a Meaning All Its Own.”

Some of her friends joined in and when the group finally emerged from the dressing room, giggling and happy, the flames were breaking the first windows on the ninth floor. Laughter turned to screams.

“We didn’t have a chance,” Rose recalls. “The people on the eighth floor must have seen the fire start and grow. The people on the tenth floor got the warning over the telephone. But with us on the ninth, all of a sudden the fire was all around. The flames were coming in through many of the windows.”

Rose ran to the Washington Place stairway door, tried to open it, and when it stayed locked she stood there, screaming. But as the crowd began to thicken, she pushed forward toward the elevator door. “I saw there was no chance at the elevators. I took my scarf and wrapped it around my head and ran to the freight elevator side. I saw the door to the Greene Street stairs was open so I ran through it and down. The fire was in the hall on the eighth floor. I pulled my scarf tighter around my head and ran right through it. It caught fire. I have a scar on my neck.”

She made it down the nine floors, meeting the first group of firemen as she neared the freight entrance at street level. There, firemen stopped her from going into the street as they were also doing in the Washington Place lobby with those who had come down from the eighth floor.

Finally, the firemen “escorted us out. I stood in the doorway of a store across the street and watched. I saw one woman jump and get caught on a hook on the sixth floor. I watched a fireman try to save her. I wasn’t hysterical any more; I was just numb.”

Where was Mary Leventhal? Her telephone did not ring to give the alarm. But Anna Gullo, as soon as she heard the screams of fire, ran across the rear of the shop toward Mary’s desk. Then she was swept along with the frantic crowd heading for the Washington Place door.

At the door she tried to exert whatever authority she could command as a forelady. She shouldered the frightened girls aside and tried to open the door.

“The door was locked,” she says.

Trapped, she soon shared the terror of those around her. She fought her way out of the crowd and ran to a window on the Washington Place side and tried to open it. The window stuck so she smashed the glass with her hand. Somewhere in the confusion she had picked up a pail of water, and thrown it at the flames.

“But the flames came up higher,” Anna says. “I looked back into the shop and saw the flames were bubbling on the machines. I turned back to the window and made the sign of the cross. I went to jump out of the window. But I had no courage to do it.”

Now Anna sought her sister. She headed back across the rear of the shop toward the Greene Street doors, shouting for her sister, Mary.

There were others who cried out for dear ones. Joseph Brenman worked with his two sisters on the ninth floor. Unable to find them, he pushed his way dazedly through the struggling crowd in the rear, calling for the younger of the two, “Surka, where are you, Surka?”

Anna fought her way to the Greene Street door. “I had on my fur coat and my hat with two feathers. I pulled my woolen skirt over my head. Somebody had hit me with water from a pail. I was soaked.

“At the vestibule door there was a big barrel of oil. I went through the staircase door. As I was going down I heard a loud noise. Maybe the barrel of oil exploded. I remember when I passed the eighth floor all I could see was a mass of flames. The wind was blowing up the staircase.

“When I got to the bottom I was cold and wet. I was crying for my sister. I remember a man came over to me. I was sitting on the curb. He lifted my head and looked into my face. It must have been all black from the smoke of the fire. He wiped my face with a handkerchief. He said, ‘I thought you were my sister.’ He gave me his coat.

“I don’t know who he was. I never again found my sister alive. I hope he found his.”

Was the stranger Max Hochfield, destined never to see his sister Esther alive again, or was it Joseph Brenman still looking for Surka?

On the ninth floor, those able to make their way up the long, obstructed aisles, pushed into the crowded rear area of the shop. Here, two tides struggled to move in opposite directions. Few knew that behind the nearby shuttered windows was the fire escape that could lead to safety.

Nellie Ventura was one of those who knew. She reached a small group at the fourth window from the left. The window had been raised, but the outside metal shutter remained firmly closed. Some banged on it with their hands. But two, working on the rusted metal pin holding the shutter closed, succeeded in lifting it. The shutters swung open. Nellie Ventura stepped over the 23-inch-high sill and down to the slatted balcony floor.

She saw thick smoke with tongues of fire at the eighth floor. “At first I was too frightened to try to run through the fire. Then I heard the screams of the girls inside. I knew I had to go down the ladder or die where I was.

“I pulled my boa tight around my face and went. I do not know how I got down to the courtyard at the bottom. Maybe I jumped, maybe somebody carried me. I remember a fireman led me through a hallway and out into the street. At first I couldn’t remember where I lived. A policeman took me home.”

Panic-stricken girls battled each other on that rickety, terrifying descent. Of her own flight, Mary Bucelli could recall only that “I was throwing them out of the way. No matter whether they were in front of me or coming from in back of me, I was pushing them down. I was only looking out for my own life.”

The last to get to safety by way of the fire escape was quick-witted Abe Gordon who, at sixteen, had started working at Triangle as a button puncher. He loved the marvelous sewing machines, the Singers and the Willcox and Gibbs stitchers, and his dream was to become a machinist.

The steppingstone to that job was the assignment as belt boy. Then his task would be to listen for the call of an operator whose machine had lost power because its strap connecting with the fly wheel on the axle had snapped. He would then sidle swiftly down the crowded aisle, creep under the machine table, and make the repair.

Abe saved twelve dollars out of his scant pay and bought a watch fob for the head machinist. In no time at all he was promoted from button puncher to belt boy.

Now, pushing out onto the fire escape, he sensed its inadequacy. “I could hear all the screaming and hollering in back of me. At the sixth floor, I found an open window.

“I stepped back into the building. I still had one foot on the fire escape when I heard a loud noise and looked back up. The people were falling all around me, screaming all around me. The fire escape was collapsing.”

Even in the midst of the horror, some failed to grasp its finality. When Yetta Lubitz emerged from the dressing room she was surprised at the sight of the commotion. As a worker “on time” rather than “by the piece,” punching out on the time clock had become a most meaningful ritual of her daily routine. She managed somehow to get through the crowd to the time clock, inserted her card in the receiving slot and pushed the punch lever. The ring of its bell seemed to awaken her to the seriousness of the situation around her. She became frightened and ran toward the dressing room.

“Then, all of a sudden, a young dark fellow—he was an operator but I didn’t know his name—was running near me. I ran with him to the Washington Place door. He tried to open the door. He said, ‘Oh, it is locked, the door is locked.’”

Now panic seized her. She ran back to the dressing room, then out of it to the three windows facing the school building—“the flames had knocked them out and were licking into the shop”—then back again into the dressing room.