The Trip to Echo Spring (17 page)

Read The Trip to Echo Spring Online

Authors: Olivia Laing

This is true, and true in particular of the marvels he produced. The idea that storytelling was a panacea, a route out of pain and danger, is reflected in a letter he wrote in 1962 to a grad student working on his books. He said that he'd become a writer âto give some fitness and shape to the unhappiness that overtook my family and to contain my own acuteness of feeling'. In darker moments, though, he'd begun to wonder if telling stories wasn't in some muddled, mysterious way related to his desire to drink. Pondering in his journal of 1966 Fitzgerald's long voyage into self-destruction, he wrote anxiously:

The writer cultivates, extends, raises, and inflates his imagination . . . As he inflates his imagination, he inflates his capacity for anxiety, and inevitably becomes the victim of crushing phobias that can only be allayed by crushing doses of heroin or alcohol.

Writers are indeed under unusual strains, and yet what this statement really conveys is an unwillingness to accept responsibility that is apparent in all alcoholic excuse notes. It was discernible in those slippery phrases

inevitably

and

can only be

â words used to give the impression the drinker is at the mercy of forces too vast and global to be resisted.

Two years on, and perhaps more conscious of the seriousness of his situation, he wrote carefully:

I must convince myself that writing is not, for a man of my disposition, a self-destructive vocation. I hope and think it is not, but I am not genuinely sure. It has given me money and renown, but I suspect that it may have something to do with my drinking habits. The excitement of alcohol and the excitement of fantasy are very similar.

Both excitements seemed related to their ability to lift him out of reality, vaulting away from a baggy and dispiriting past; an increasingly disorderly and dismaying present. Trying to work out the details was like unsnarling fishing line, though. And, thinking that, I remembered again what Cheever had done with his own memories in

Falconer.

The novel is set in a prison and concerns a well-bred heroin addict called

Farragut. While in the throes of withdrawal, a prison guard asks Farragut: âWhy is you an addict?' The question provokes a flood of memories that end with Farragut at fifteen, driving to Nagasakit to stop his father from killing himself by jumping into the sea. He runs along the beach, hearing all the while the sound of the clack of cars on rail-joints. At the amusement park a laughing crowd had gathered to watch Farragut's father on the rollercoaster, pretending to drink from an empty bottle while pantomiming that he's about to leap. Farragut asks the boy at the controls to bring him down and so Mr. Farragut stumbles out and rejoins his son, âhis youngest, his unwanted, his killjoy'. âDaddy,' says Farragut, âyou shouldn't do this to me in my formative years.' And there the monologue ends, with Farragut's own heavily ironic repetition of the prison guard's question: âOh Farragut, why is you an addict.' This time, though, he doesn't bother with a question mark. The story says it all.

There were rocking chairs at Charlotte airport and one of the concession stands sold barbecue. The flight to Miami was delayed and by the time we boarded it was already evening. The runway was marked out in glowing dots of green and blue and larger splashes of red, the dark bulk of the city beyond a scattering of gold. A swift sense of pressure in the feet, then we were up in wispy cloud the colour of smoke, and then out into the unencumbered ink-blue of night. I had a sense of being cut loose from all my body's usual routines, and yet I was deeply relaxed, both physically and in my heart.

We were circling back to the south now, to Florida, that swampy, subtropical peninsula where the rich come to luxuriate and the poor to make their fortunes. Hemingway country. There are many regions of America associated with Hemingway, among them Michigan, Wyoming and Idaho, but Florida â or rather the ocean that surrounds it â is where he spent some of his happiest days, fishing for marlin from his black-hulled boat

Pilar,

all the friends he could muster aboard. Florida was the first place he came to after Europe, and he remained based there throughout the decade of his marriage to Pauline Pfeiffer.

They left Paris together in March 1928. Pauline was six months pregnant and in an endearing letter to his new wife written aboard ship he expressed the impatient hope that they would soon stop bouncing around on the bloody Atlantic: âOnly lets hurry and get to Havana and to Key West and then settle down and not get in Royal Male Steam Packets any more. The end is weak but so is Papa.'

In Key West they took an apartment while waiting for their new Ford coupe, a present from Pauline's rich Uncle Gus. On the morning of 10 April, an unexpected reunion occurred. A few weeks back, Hemingway's parents had written to him in Paris, telling him of their upcoming holiday in St. Petersburg, Florida. The letter hadn't yet recrossed the Atlantic, and so Hemingway had no idea his parents were near by, while they assumed he was still in France. Partway through their vacation, they'd gone to Havana for an excursion. They were coming back into Key West on the ferry when Hemingway's father spotted a hunched-over figure fishing on the pier.

Like Vassya in Chekhov's story âThe Steppe', who can see hares washing themselves with their paws and bustards preening their wings, Dr. Clarence Edmonds Hemingway was blessed with remarkably good vision. Recognising his son's stocky form he whistled like a bobwhite quail, the familial call. Ernest jumped up and ran to meet them. Grace â âthe all-American bitch' â was glowing, but Ed had lost weight, and looked old and exhausted, his neck scrawny inside the wing collar shirt he always wore. All the same, he was delighted to see his son. âLike a dream,' he wrote a day or two later, âto think of our joyous greeting.'

Hemingway rushed his parents off to meet Pauline, though neither had been exactly thrilled when they heard of his divorce. (âOh Ernest, how could you leave Hadley and Bumby?' his father had written on 8 August 1927. âI fell in love with Bumby and am so proud of him and you his father.') According to his sister Marcelline's soapy and not always reliable memoir

At the Hemingways,

their surprise encounter went some way to salving this wound. âDaddy wiped a tear from his eye as he told me about it,' she wrote. âThis meeting with Ernest meant much to our parents, especially to Dad, for he had missed Ernest during the estrangement.'

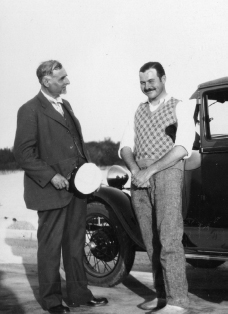

There's a photo of the two Hemingway men taken that afternoon, standing by a flashy car that looks black against the sun. Ernest is leaning into it, in socks and light trousers, a jaunty Argyle vest and a shirt so white his shoulders merge in with the sky. His hands are clasped in front of him and he looks somehow both naughty and angelic, smiling knowingly at the photographer, his dark hair Brylcreemed back. There's a little dark object under his arm that resembles a hot water bottle cover â a sweater, perhaps.

Dr. Hemingway isn't looking at the camera. He's turned to gaze intently at his son. He's wearing a three-piece suit and tie, warm clothes for the climate, and holding in his hand a sailor's cap. His nose and chin look very sharp, eyes deeply set, just like the famous description of Dr. Adams, the man he both was and wasn't, that would soon appear in âFathers and Sons'. It's all there: âthe big frame, the quick movements, the wide shoulders, the hooked, hawk nose, the beard that covered the weak chin,' the famous eyes, that saw âas a big-horn ram or as an eagle sees, literally.'

If you asked Ernest, he'd say Dr. Adams, the father in the Nick Adams stories, bore no relationship to Dr. Hemingway beyond the coincidence of their professions, their place of residence and the miracle of their vision. In fact, three years back, on 20 March 1925, he'd written his father a letter explaining just that. âI'm so glad you liked the Doctor story,' he said. âI've written a number of stories about the Michigan country â the country is always true â what happens in the stories is fiction.'

Maybe. Maybe not. In a letter written in 1930 to Max Perkins, he changed his tune, saying of

In Our Times,

the collection that included âThe Doctor and the Doctor's Wife': âThe reason most of the book seems so true is because most of it is true and I had no skill then, nor have much now, at changing names and circumstances. Regret this very much.'

Either way, the events in âThe Doctor and the Doctor's Wife' play off the dynamic Hemingway most hated in his parents. It opens with Dr. Adams down on the shore of the lake, trying to organise a team of Indians to saw and split some logs that have washed up on the beach. They've broken loose from the big log booms and the doctor assumes

they'll rot there and never be reclaimed. One of the men, Dick Boulton, who is what Hemingway calls a âhalf breed', accuses the doctor of stealing the logs. He has his men clean off the sand and find the mark of the sealer's hammer, which identifies it as the property of White and McNally. The doctor tries to bluster his way out, but he isn't nifty enough and eventually he makes the mistake of challenging Dick to a square fight. Then he backs down and walks away. The men on the beach watch as he retreats, stiff-backed, up the hill to his cottage.

In the second phase of Dr. Adams's humiliation, he has a conversation with his wife through the wall that separates their rooms. She's in bed with a headache, blinds down, playing swift hands of martyrs' cards. Henry cleans his shotgun, while his wife quotes homilies from the Bible and denies the reality of everything he says. âDear, I don't think, I really don't think that anyone would really do a thing like that,' she calls through the wall, as he spills yellow shotgun shells on to the bed. He goes out then and the screen door slams behind him and he hears his wife's aggressively muted intake of breath. He apologises and walks into the woods, where he finds Nick sitting against a tree, reading a book. He tells the boy his mother wants to see him, but Nick doesn't want to go. âI know where there's black squirrels, Daddy,' he says. âLet's go there,' Dr. Adams replies, and with this consoling exchange they disappear together over the threshold of the page.

Despite its ending, something dangerous was flickering in that story, and it surfaces again in âNow I Lay Me', the Nick Adams account of trout fishing and sleeplessness that I'd been brooding over on the night train down through Carolina. âNow I Lay Me' was written the summer before Hemingway arrived in Key West and was published in

Men Without Women

a few months later.

On the nights when Nick can't manage the trick of fishing in his mind, he stays awake by remembering everything he can muster about his early years. First of all, he thinks of everyone he's ever known, so that he can say a Hail Mary and an Our Father for them. He begins this process with the earliest thing he can recall, which is the attic of the house where he was born. There are two things he says about this attic: that his parents' wedding cake hangs from a rafter in a tin box and that there are jars of snakes and other specimens up there that his father collected as a boy. The snakes are preserved in alcohol, but the alcohol has begun to evaporate and the exposed backs are turning white. He says there are many people he can remember and pray for, but he doesn't name them. The only things present are the cake in the tin box and the whitening snakes.

At other times, he continues, he tries remembering everything that has ever happened to him, which means working back from the war as far as he can get. This takes him immediately into the attic again. From there he works forward, remembering that when his grandfather died his mother designed and built a new house, and âmany things that were not to be moved' were burned in the back yard. What an ambiguous phrase this is. âWere not to be moved', as in too precious to be moved, a prohibition that might be given to a small boy, or âwere not to be moved' as in too insignificant to bother transporting to the new house, the sort of command a child might overhear a parent giving to a servant?