The Trip to Echo Spring (25 page)

Read The Trip to Echo Spring Online

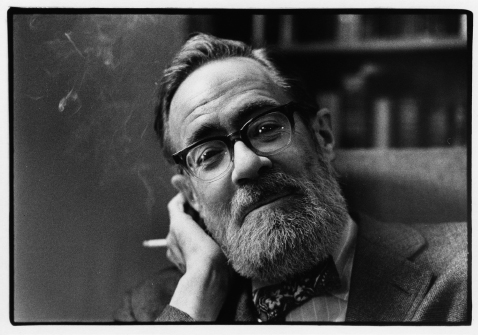

Authors: Olivia Laing

The workload was heavy and that year he suffered badly from insomnia. He often spent whole nights walking around Detroit, going into university gaunt and smelly to teach what were by all accounts inspired classes, in which he held forth on Shakespeare or poetry, quoting great gouts by heart. He trembled as he talked, and paced the room, his voice getting higher and higher as his excitement grew. When he returned to the apartment he shared with a married couple, he'd frequently faint as soon as he walked through the door. Coming to Wayne had been, he began to think: âan insane mistake, and I am paying â in health, in temper, in

time

'. He was barely eating and sometimes suffered hallucinations and yet he refused to stop his frantic programme of reading, teaching and study. A doctor made a tentative diagnosis of

petit mal

epilepsy, while a psychiatrist thought he was neurotic and in imminent danger of complete nervous collapse.

Slowly, he pulled himself together. In 1940 he took up a post as an instructor in English literature at Harvard, where he spent a great deal of time with the poets Robert Lowell and Delmore Schwartz, both of whom drank heavily and also suffered from turbulent mental health. In 1942, he married Eileen Mulligan, a dark-haired, quickwitted girl who later became an analyst. After a few years of jobbing lectureships, they moved together to Princeton, where he taught

creative writing while working on an analytical biography of Stephen Crane and a study of

King Lear,

as well as publishing his first volume of poems,

The Dispossessed.

Until this point he'd drunk only socially, but in 1947 events precipitated a great shift in both his writing and his habits. He fell in love with a colleague's wife and began an affair, simultaneously anatomising it in a feverish sequence of sonnets. This was the moment, he figured later, when he began to drink seriously, both to choke back his guilt and to fan the flames of his desire. Eileen agreed. In her marvellously lively memoir of their life together,

Poets in Their Youth,

she remembered him at the time:

. . . alternately hysterical and depressed, couldn't sleep, had violent nightmares when he did and, most disturbingly of all, was drinking in a terrifyingly uncharacteristic way . . . For John, who awakened guilt-ridden and exhausted from a battle with demons, a âbrilliant' martini became the cure for a hangover, a nightcap or two the cure for insomnia.

During this period he started a poem about Anne Bradstreet: at once a biography and a seduction in verse of the long-dead, pox-spotted New England poet. âHomage to Mistress Bradstreet' almost killed him, but it was good: hot to the touch, exquisitely wrought. There's a verse in it I love, a homage at once to the magical facility of the biographer's art and to the intimate kinship one can feel for the long dead. The poet speaks directly to Anne's ghost, summoning her back by the magnetic force of his devotion.

Both of our worlds unhanded us. Lie stark,

thy eyes look to me mild. Out of maize and air

your body's made and moves. I summon, see,

from the centuries it.

I think you won't stay. How do we

linger, diminished, in our lovers' air,

implausibly visible, to whom, a year,

years, over interims; or not;

to a long stranger; or not; shimmer & disappear.

What followed on the poem was not good, however. In 1953, the year of its completion, Eileen left Berryman, worn to despair by his anxiety, drinking, promiscuity and toxic guilt. He moved to the Chelsea Hotel in New York, where his old friend Dylan Thomas was also staying. On 4 November, Thomas collapsed in his room after guzzling whiskeys in the White Horse. He was taken to St. Vincent's Hospital in the Village, where a few days later Berryman walked into the temporarily unattended chamber to find him dead in his oxygen tent, his bare feet sticking out from beneath the sheet. It was a warning â one perhaps too demanding to translate.

In 1954, Berryman was hired to teach a semester of creative writing at the University of Iowa, where two decades on John Cheever and Raymond Carver would also struggle to balance their compulsions and their duties. On his first day, he fell down the stairs of his new apartment, smashing through a glass door and breaking his left wrist. He taught in a sling, inspiring and relentless as ever despite a gathering depression. The poet Philip Levine, one of his students that year, later wrote an elegy to

his former teacher entitled âMine Own John Berryman': a testament to his decency and commitment to literature.

He entered the room each night shaking with anticipation and always armed with a pack of note cards, which he rarely consulted. Privately, he confessed to me that he spent days preparing for these sessions. He went away from them in a state bordering on collapse . . . No matter what you hear or read about his drinking, his madness, his unreliability as a person, I am here to tell you that in the winter and spring of 1954, living in isolation and loneliness in one of the bleakest towns of our difficult Midwest, John Berryman never failed his obligations as a teacher.

The work ended abruptly that fall, though, when he got into a drunken altercation with his landlord. He was arrested and spent a night in a cell, where the cops apparently exposed themselves to him. When news of this humiliating escapade seeped out he was summoned before the Deans and fired from his job. Luckily, a friend found him a post at the University of Minnesota, which would for the rest of his life serve as a home base. He took an apartment in Minneapolis and began a new sequence of poems he called the Dream Songs.

They're like nothing else on earth, these mixed messages of love and desperation. The closest comparison I can think of is Gerard Manley Hopkins, had Hopkins been a philandering alcoholic at large in the twentieth century, hip to its rhythms, its cobalt jazz. Three stanzas of six lines, speedy, impacted, full of

emphasis

and â gaps. Henry at the centre, Henry Pussycat, Huffy Henry, sometimes called by his

unnamed companion

Mr. Bones.

The two men's voices range in ways no poetry had till then, soaring and slouching through dialect, baby talk, slang, the archaic gleanings of a Shakespeare scholar. As it grew, the poem gathered shape: passing Henry out of life to death and back again. All the while he complains, harping on about his dismal life, his lost father, his dead and living friends, his alcoholism and his troubles with the compact and delicious bodies of women. Henry is a man in a confession booth, hungry for solace of all kinds, berating, like Job, a God he can't quite admit either to or in.

Outside the poem, a period of domestic peace began. A week after his divorce from Eileen was granted in 1956, Berryman married Ann Levine, a much younger woman he'd met in Minnesota. That year, he was given a Rockefeller Fellowship, and in 1957 won the Harriet Monroe Poetry Prize for

Bradstreet

. Shortly after, Ann gave birth to a son, Paul, nicknamed Poo. âHe is getting a pot, his second chin is wicked to contemplate, his skin is ravishing all over, and he smells good,' the new father wrote dotingly, though he'd come rapidly to resent the division of Ann's attentions.

After months of fighting, she left him in January 1959, taking the baby with her. Berryman began drinking harder than ever then and a few weeks later, after an attack of delirium tremens, was admitted to Glenwood Hills Hospital on Golden Valley Road, Minneapolis, a closed ward for alcoholics. Despite being in the throes of what he described as âmental agony, broken health and the double wreck of my marriage', he kept up the pace of work and study, writing and rearranging Dream Songs and staggering out by taxi to teach his classes. Released, he drank again; returned again. His sleep was wretched, even with sedatives, âso I'm nearly dead all the time'.

The two things, writing and drinking, ran concurrently. Later that same year he spent a November day in the university library reading books on the history of minstrel shows, trying to see if he could work the Tambo and Bones routine into the Dream Songs. From this came the decision to give Henry his companion, his rueful witness and sparring partner. That same night, staggering drunk into the bath, he fell and twisted his right arm. Man down. Man going on.

In 1960, he took the opportunity to wheel south, accepting the offer of a spring semester at Berkeley. From this uncertain refuge he wrote gleefully to a friend: âI get through the most marvellous quantities of liquor here, by the way. I dont drink as

much

as I did in Mpls, but I enjoy it much more, because I don't go to bars, I just order it in and settle down with it.' He'd been teaching with his usual flair and rigour, but in his free time suffered intensely from isolation and paranoia, though this lightened a little when he met a Catholic girl called Kate Donahue, herself the daughter of an alcoholic, who in 1961 became his third and final wife.

On it went. In 1962, he spent a summer at the Bread Loaf residency, writing Songs and drinking gin martinis. By fall his behaviour was erratic. He shouted, sometimes sobbed. In November he went unwillingly to McLean's Hospital outside Boston, where Robert Lowell was also treated. On the third day he promised never to combine liquor with writing poetry again. He was released on 1 December, dry seven days, and twenty-four hours later his wife gave birth to their first daughter, Martha, soon to be known as Miss Twiss.

Another injury, almost comical this time. The next day he visited Kate and the baby in hospital, then took a celebratory drink with friends. Somehow the cab home succeeded in running over his foot

and breaking his ankle. When he missed an appointment with his psychiatrist, friends were sent to track him down. They found him holed up in bed, his foot already festering. Taken to the emergency room he bellowed: âI feel like a minor character in a bad Scott Fitzgerald novel.' The next day, very drunk again, he accused Kate of neglecting him.

In 1964 he was hospitalised three times, spilling Dream Songs all the way. No wonder he described Henry grievingly as âlosing altitude'; no wonder he seemed to be âout of everything/save whiskey & cigarettes'. And yet the good news kept coming; kept somehow failing to plug the gap. On 27 April,

77 Dream Songs

was published. The reviews weren't as warm as he would have liked, particularly the one from his old friend Lowell (âAt first the brain aches and freezes at so much darkness, disorder and oddness'), but there were critics â and better yet, poets â who got what he and Huffy Henry were about. Writing in the

Nation

, Adrienne Rich described it as âcreepy and scorching', observing âhis book owes much of its beauty and flair to a kind of unfakable courage, which spills out in comedy as well as in rage, in thrusts of tenderness as well as defiance'. There were other compensations too. That year he won the Russell Loines Award and the next he was awarded a Pulitzer.

In 1965, the combination of success and self-destruction accelerated. He broke his left arm walking in socks on a wooden floor; wrote to his friend William Meredith: âI've been in & out of hospitals so often lately I'm dizzy.' He was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship to continue work on the Songs, and in 1966 used the money to take his family to Ireland for a year. In Dublin he met the poet John Montague, who later felt moved to comment:

Berryman is the only poet I have ever seen for whom drink seemed to be a positive stimulus. He drank enormously and smoked heavily, but it seemed to be part of a pattern of work, a crashing of the brain barriers as he raced towards the completion of the

Dream Songs.

For he appeared to me positively happy, a man who was engaged in completing his life's work, with a wife and child he adored.

It was a half truth, at the very best. On New Year's Day 1967, he fell and hurt his back, damaging a nerve. In April he was committed to Grange Gorman mental hospital to detox. In May he flew back to New York to collect an award from the Academy of American Poets, staying at the Chelsea Hotel, never a safe place. When friends found him vomiting blood they took him to the French Hospital, âall but dead'. He submitted to treatment, insisting on keeping a half pint of whiskey by his bed. Another Dream Song: âHe was

all

regret, swallowing his own vomit, / disappointing people, letting everyone down / in the forests of the soul.'

That autumn

Berryman's Sonnets

came out â the ones he'd written in Princeton in the white heat of his affair. In 1968 the second volume of Dream Songs,

His Toy, His Dream, His Rest,

was published, followed the next year by

The Dream Songs,

the collected volume. The honours, too, kept flooding in.

His Toy

was awarded the National Book Award for Poetry and the Bollingen Prize. He was appointed Regent Professor of Humanities at Minnesota and gave readings countrywide. And then, on 10 November 1969, he was admitted to Hazelden, a hospital in Minneapolis, with acute symptoms of alcoholism and a sprained left ankle, caused by tumbling over in his own bathroom.

This time he didn't just dry out, buoyed up on thorazidine. Hazelden was one of the pioneers of the Minnesota Model, the then radical, now commonplace technique of treating alcoholics as in-patients in therapeutic communities, where they follow the Twelve Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous, attend lectures and learn, through constant challenging and self-exposure, how to lay down the defences that perpetuate their disease.