The Trouble with Chickens

Read The Trouble with Chickens Online

Authors: Doreen Cronin

The Trouble with Chickens

A J.J. Tully mystery

DOREEN CRONIN

illustrated by

KEVIN CORNELL

For Lillian, John, Vince, and Marge

âD.C.

For Kim, who holds my hand

âK.C.

Â

Â

I

t was a hot, sunny day when I met that crazy chicken.

So hot that sometimes I think the whole thing may have been a mirage.

But mirages don't have chicken breath, mister.

She was a short, tired-looking bird with a funny red comb on her head.

It looked about as useful to her as a spoon is to a snake.

Her eyes were tiny and black, and set so close to each other they practically touched.

I'd be surprised if the right eye could report back seeing anything other than the left eye.

Chickens make me nervous.

Can't keep 'em quiet.

We stared at each other for an awkward moment.

I nodded to tell her to move on.

She picked up her left foot carefully, not sure whether she should back out of my sweltering doghouse.

As her foot hung in midair, she lowered her pointy white head and very deliberately said . . . nothing.

A phone rang.

A car backfired.

A blender roared.

And that crazy chicken didn't blink.

She was one tough bird.

M

y name's Jonathan. Jonathan Joseph Tully.

J.J. for short.

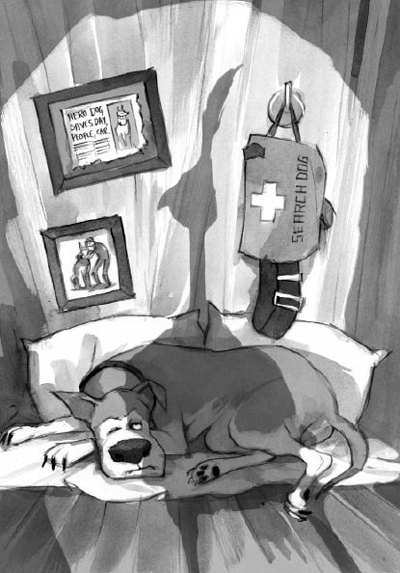

I spent seven years as a search-and-rescue dog.

The quiet life in the country where Barb, my trainer, lived was my reward for all those years of service.

Some reward.

I could track the six-day-old scent of a lost hiker and pull a fat guy out from under a pile of rubble, but I couldn't get that crazy chicken out of my yard.

Her name was Millicent.

I called her Moosh, just because it was easier to say and it seemed to annoy her.

She had two little puffy chicks with her.

She called them Little Boo and Peep.

I called them Dirt and Sugar, for no particular reason.

Moosh had got the word that I knew how to solve problems.

Boy, did that chicken have problems.

“I'll pay you in chicken feed,” said Moosh.

That was the chicken's first problem.

I don't work for feed.

“No dice,” I replied.

Dirt and Sugar were bathing in my water bowl.

“I'll pay you in feathers.”

That was the chicken's second problem.

“I already got a pillow,” I grumbled.

Dirt and Sugar were playing in my food bowl.

Crazy chicks.

I was losing patience.

“I'll work for a cheeseburger. Take it or leave it.”

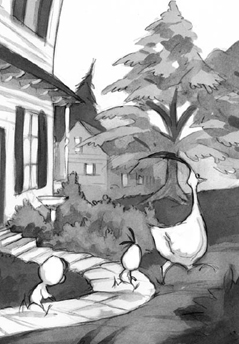

Moosh's tiny chicken head cast a huge, pointy shadow against the side of my weather-beaten doghouse. She took a step away from me, turning her head to glance at Dirt and Sugar. Those two feather balls jumped out of my water bowl and rolled around in the grass. They looked like they didn't have a care in the world, but their mom sure did.

A passing cloud offered some uncertain shade from the sun.

Moosh's big, pointy chicken shadow finally moved.

“Done,” said Moosh.

“Well done,” I cracked.

I thought she smiled, but it's tough to tell with a beak.

M

oosh paced back and forth.

Dirt and Sugar followed behind her.

As Moosh took a step forward, Sugar fell into line right behind her. I expected Dirt to do the same. For some reason, she waited two beats, then got into line.

Dirt left enough space in between herself and Sugar to park a squirrel.

I'm no chicken expert, but something wasn't right.

“Who's missing?” I asked Moosh.

The truth was somewhere between her brain and her beak.

I wasn't sure it would survive the trip.

“Spill it, Moosh,” I grunted.

She was getting on my nerves.

Dirt and Sugar stepped out from behind their mother.

They were half yellow, half whiteâlike fuzzy popcorn kernels with feet. They were new enough to this world to be spitting up eggshell. Their eyes were wide and young, and close-set like their mother's.

Sugar cocked her head, stepped out from behind her popcorn sister, and motioned with one tiny wingette for Dirt to stay behind. A ladybug flew into the doghouse and crawled across the floor, oblivious to the chicken tension building in the room.

I growled.

Sugar peeped.

I growled again.

Sugar took a step closer, bracing herself against the water bowl.

“Poppy and Sweetie are missing,” she whispered.

She may have looked fluffy and new, but this chick had already learned that life outside the shell was not all it was cracked up to be.