The True Detective (57 page)

Read The True Detective Online

Authors: Theodore Weesner

Tags: #General Fiction, #The True Detective

“It’s hard for me to say,” she says.

“I realize that, Claire. That’s okay. What is it?”

“I don’t have any money,” she says.

A moment passes, and she adds, “I wondered if there might be some city agency I could borrow from to pay for Eric’s funeral and burial? I will certainly repay the money.”

There is no such agency, and Dulac responds by saying, “What about Eric’s father? Apparently he doesn’t have any money, but he does have a job. We could have him—”

“No,” she says. “No. I couldn’t do it. I don’t want his money. I want to bury my son myself.”

On a pause, Dulac says, “There’s no one you can borrow from?”

“I just can’t ask Betty and John. I can’t do that. They’ve done so much for me. I don’t want to lose them as friends. I just thought, if there was some agency I could borrow from, then I would repay the money as soon as I can. Matt could get a job, too, and we could take care of it.”

Dulac pauses again, before he hears himself say, “Well, there is an emergency fund at the police department. I’ll tell you what you do. You go ahead and order what you need; charge it to the Portsmouth Police Department. I’ll call the funeral home in the morning, so they’ll know. Then you just use my name. Okay? So

just put it out of your mind for now. Tell them to refer all bills to me, care of the Portsmouth Police Department.”

After a moment, seeing her back to the front door and saying good night, Dulac leaves to drive home at last, to see if he may come back down to earth from whatever odd dimension it is he seems to be traversing. He longs all the more to be with Beatrice. She will forgive him. At last, and unlike any other person—it is the product of their years together—she will forgive him. They will go out, go to Jimmy’s on the river, and he will tell her how he has committed their savings—they have about three thousand dollars in the credit union—to pay for a funeral, and she will look at him and shake her head at him, but will remain on his side in her way, and they will go ahead and have too many drinks, and probably go out on the small lighted floor and cling to each other in some lumbering forgotten dance of their life together—two oversized creatures seeking equilibrium, matched as a pair, the King and Queen of their bungalow on their small street in their small town—but he will not, not now or ever, reveal to her any more than a little of what he knows.

30

M

ATT IS DIALING IN A NEW STATION

. T

HE OLD RADIO

,

REPAINTED

avocado by hand and shaped like a toaster, is on a littered workbench in John and Betty’s basement. Matt has been

reluctant to change the radio’s setting, as he had been reluctant to turn the radio on in the first place, for it had been presumed that he came down here to be by himself, to be alone with thoughts of his brother.

In truth, he knows, he is here to be away from all that is going on upstairs. He’d feel okay. Almost okay. Then someone—his mother usually—would start in and her sobbing would have tears coming up in his own throat, headed for his eyes. He didn’t want to cry anymore. He didn’t want to hurt anymore. Eric himself, he has thought, wouldn’t want to be caught in that scene upstairs. It was at times like these, in fact, in odd situations and in strangers’ houses, that they did more together, had more fun as brothers, than at any other time. And down here now, it isn’t so bad. It’s like one of those good times, those fun times. And so he is alone with thoughts of his brother.

It is as Matt is standing with his back to the workbench then that a radio news report comes on, and against an initial urge to search for more music—he’s heard and seen enough reports already—he lets the radio have its way. He stands and hears.

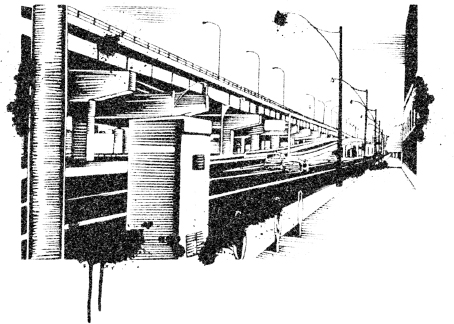

The suspected killer of twelve-year-old Eric Wells of Portsmouth has been identified as Vernon R. Fischer of Laconia. The body of the twenty-two-year-old senior honors student, who died late this afternoon in a death leap from the I-95 bridge between New Hampshire and Maine, has been recovered from the Piscataqua River by state police and Coast Guard crewmen. Chased by foot onto the bridge by Portsmouth Police Lieutenant Gilbert Dulac, the ten-year resident of the state is reported to have leaped from the bridge to elude capture.

Although they are continuing their investigation, Portsmouth police speculate that this is the final chapter

in a bizarre abduction-murder case which has stunned the Seacoast area over the past several days, beginning on Saturday evening when the twelve-year-old boy disappeared while walking home. His sexually molested body was discovered before noon today next to the parking lot of an office supplies store on Islington Street, less than two blocks from where he disappeared.

In a related story, forty-nine-year-old Warren Wells, reportedly of New Orleans and the father of the victim, was arrested this evening by York County, Maine, authorities only moments after he stepped off a plane at Portland National Airport. He is charged with being over twenty-six thousand dollars in arrears on support payments, a felony carrying a maximum sentence of three years in prison upon conviction. A spokesman for the County Sheriffs office reports that the boy’s father will be kept overnight in the county jail but will be released, on his own recognizance, to attend his son’s funeral. Eric Wells’s father is described by authorities as being a man with a lot of personal problems who is very upset and heartbroken about his son’s death. At the same time, the bereaved father will be asked to agree to a twenty-five-thousand-dollar personal bond, which requires no posting of money, and to sign a pledge to comply with a court order to bring overdue support payments up to date. Wells and his former wife, Claire, were divorced in June 1974.

Most of his friends, most of the kids in school, Matt knows, would not have tolerated even that much talking before searching for sounds along the dial rather than words. Even those words. He knows, too, has a glimpse in this moment, that by Monday in school the incident, the story of his brother, will be forgotten and life will be rolling along as it always has, toward

Friday or Saturday, and as it says in all the songs, he will be the only one who remembers. He and his mother. Maybe his father, too. And he knows, too, at last, that his mother was right after all, and that he will not dislike his father for it, but his father could have saved them all, long ago, could have led them elsewhere than here, and he failed.

Matt knows this as he stands here. A moment standing before a cluttered workbench in a basement, while a radio plays and he is alone with his thoughts and his thoughts of his brother. He has stood here through the news, and perhaps some of it was news to him, although he has taken it in rather as he takes in music, as a commodity to feel more than to weigh and measure, as a shivering over his skin, a stillness in his mind.

He is on his own now, he thinks. More or less. Well, no more or less about it. It’s true. It is what he knows as he stands here. He is on his own now.

FTERWORD

OING

H

OME

JULY 1981

G

ETTING RID OF HIS CLOTHES

was easy. So was selling his car, for next to nothing. What has her feeling uncertain is what she is doing now, taking this drive this evening, out of town, to dispose of his personal belongings. Letters, photographs, keepsakes, his papers from school. They are in the trunk behind her, in cardboard boxes of odd sizes. The final contents of his wallet are there, too, all but two fives and two singles she removed at last, just an hour ago, separating them from each other and folding them over three times, as she always folded money, and pushing the folds into the rear left pocket of her jeans.

The urn with his ashes is in the trunk, too, lodged between boxes. She is taking it along to throw it away. Screw it, she has said to herself at last, concerning the urn. She has to get rid of it. She cannot stand having it in the house, speaking to her,

telling on her,

it seems, however hidden away it may be in a closet or even in the attic. The little sonofabitch, she thinks. Goddamn him. He messed things up for both of them in life; she’d be goddamned if she’d let him do the same in death. No way.

She has an idea by now for the twelve dollars, too, something she sees as symbolic, a secret gesture of good-bye and farewell. At the end of this drive, this curious mission, she will treat herself to a couple drinks—at work, to be among the only friends she really has anymore. She will have a couple drinks and decide for herself once and for all if she can continue to live in Laconia or if she should sell out and return, say, to San Diego, where she believes she can pick up some of the threads of the life she left behind, even if it was nearly a dozen years ago, when it was excited with the general activity of the war in Southeast Asia.

One way or another, she tells herself, her drinks will mark an end and a beginning. This very summer night. She’ll sit at the bar, just like a customer, and take a look around herself. She hopes, she prays, that they kid her for coming in on her night off. They better, she thinks. It’s what she needs, she thinks, especially tonight.

People would laugh if they knew of this mission she had undertaken, but it’s the only way she has thought of to get rid of his things. She has neither wood stove nor fireplace in her small house, and the town dump, with banker’s hours, run like a clinic, was out of the question, even if it did have a central incinerator. For it had sheds and office space, too, and the men who worked there examined everyone’s garbage in their bureaucratic authority. She could see them pinning up her son’s driver’s license, or the newspaper with the headline,

TOWN

’

S FIRST MURDERER IN NINE YEARS

, or even some of those pictures of little gay boys which, among other things, had been returned by the police. No, she did not want anyone keeping souvenirs, because if they did, she knew she would have no choice about staying here. She had similar fears about burying his things in the woods. A dog would dig everything up two years down the road, and it would be in the paper all over again, and she’d be paralyzed again in her helpless embarrassment. She has this plan then, heading south on 93, to turn into the elaborate Mall of New Hampshire, near Manchester, find a dumpster in the midst of its loading ramps, dump in everything, knowing it will make its way to a roaring incinerator which will reduce it to nothing, charge a blouse or stockings at Filene’s to validate the shopping excursion she has mentioned to friends at work, and return to her meeting with herself at the bar, to two or three or four short screwdrivers, to the first moments of the rest of her life.

She drives on. Right now, to the right, the sun is a dusty orange ball between tree masses and curves in the land, is falling and fading quickly. There are shadows in the highway valleys, where night is coming up from the ground; a car passes across the green, landscaped median with its headlights on—she turns hers on, too—and she begins to have a sense not of driving south but of driving north in her childhood, riding in the back seat of her parents’ car in the summertime and heading north for recreation. It’s what people are doing here, she decides, what they do all summer. Drive north for recreation. For freedom, really. To be free of heart. Lake water, campsites, high spirits, and cocktails—freedom. So it will be for her, she thinks, in half an hour, when she has completed her task and is heading north again. It will be as it was then. Freedom.

T

URNING INTO THE

mall, which at a distance looks a little like Las Vegas with its lights and neon reaching into the darkening sky, she is having doubts only about the urn. She hopes it will melt. She believes it will. Throwing it into a lake or river has occurred to her, but was rejected on a fear, an image, of some fisherman snagging it with a hook, dragging it in and reading the name, and everyone celebrating all over again the history she had produced. Nor did she care that all that was left of him might be reduced to smoke and disappear completely, for she had yet to burden herself with beliefs of forever after. She wants him gone, she tells herself. It’s pathetic, she knows, but she wants him to disappear entirely, for it seems her only chance.

The dumpster she finds is in an ideal location. Driving slowly and carefully into an opening in the mall’s exterior, she finds herself, under floodlights, at the rear loading area of a

supermarket and other rear entrances, next to a blue dumpster nearly as large as a railroad car. Turning off the motor, she slips from her car and goes around to open the trunk lid. Nearby, a generator runs insistently. She pauses, to double-check. An odor of decomposing food is in the air, but no one is around. From ground level, she can see on one end a tumbling stack of folded cardboard boxes and the thin wooden and wire crates used for shipping produce. Maybe the dumpster will be emptied soon. It satisfies her to think that the fire might take place as soon as tomorrow or the next day.

She lifts out the urn first. Now or never, she thinks. Hefting it like a shotput up into the dumpster, she thinks ashes to ashes. It

thunks!

hitting at least close to the steel bottom. It will be covered, she thinks. If not now, with the boxes she has to empty, then with other garbage. She feels some relief. The worst is over. Good luck to you; good riddance, too, she thinks.