The Truth About Lorin Jones (42 page)

She looked at the card, which had a bird on it, a white peace pigeon — no, a dove, probably; religiously inappropriate, too. “Happy New Year to Polly.”

For God’s sake, she thought; it must be twenty years since her father had sent her anything. She pulled the paper apart and drew out a box marked — holy cow! — ETCH A SKETCH. The same damn Etch A Sketch she had longed for when she was eight years old, that her father had so often promised and never brought her. Polly began to laugh; then, surprising herself, to cry.

Weeping foolishly, she took her father’s check into Stevie’s room, so that he’d find it there when he came home for supper. The sight of his books and posters, now restored to the shelves and walls, restored Polly slightly. Whatever happened to her, Stevie was back in New York.

Yes, but what would he find here? she thought, looking up at an old wildlife poster that hadn’t yet been replaced with something more contemporary, maybe because it hung high in a corner. It was a blown-up color photo of a raccoon that Polly had bought many years ago because of the animal’s resemblance to Stevie as he had been at four or five: the round dark eyes set in a ring of almost transparent darker skin, the pointed face and clever, inquiring expression. He still looked like that, a little.

The junior high school Stevie was about to return to was, according to report, worse than ever this year. Both his best friends had now left it: one for Ethical Culture and the other for Exeter. But Polly couldn’t afford to send Stevie to private school; he would have to stay where he was, in crowded, boring classes, a raccoon child threatened or attacked by teenage pit bulls. After a while, and not such a long while either, he might want to go back to the wilderness, to Denver; to Jim’s so-called normal American family, which would soon be even more “normal.”

But suppose she were to write the book Garrett wanted, Polly thought, and become his assistant. Then she could afford to send Stevie to a private school, and soon he would be one of those sophisticated preppie kids you see around Manhattan. With an elegant mother who wasn’t home very much, because in her new super-career Polly would often be out of town or at parties and openings. She would have to hire a housekeeper, so that when Stevie came home from his snobby school there would be someone here to make his supper.

These visions, and the idea that she now had to choose between not only her own two unattractive futures, but also Stevie’s, terrified and enraged Polly. In spite of the warmth of the apartment she was overcome with a kind of feverish shiver, as if she were coming down with the flu.

But was there any other alternative? As she stared up at the poster, its background altered in her imagination. The leaves of the tree became larger and shinier; brilliant tropical flowers appeared among them. The raccoon turned into Stevie at his present age; but barefoot, tanned, and dressed in a pair of cut-offs and a T-shirt, straddling the branch. Below him, on the deck of a house in Key West, Polly herself (equally tanned) sat at a picnic table typing. She wore her old jeans and a faded shirt; her hair was tied back with a piece of red yarn, and she was smiling. It was the real story that she was typing, the whole truth about Lorin Jones, with all the contradictions left in. While she watched, Mac came out of the house, carrying two cans of beer.

That can’t happen, Polly thought, it would be crazy, you know you can’t trust him. It would be crazy to trust somebody like Mac when every man she’d ever known, beginning with her father, had hurt her and abandoned her.

But Carl Alter had said that she’d abandoned him, that she hadn’t wanted to see him. He really believed that. Jim probably believed that too. For them she was like Lorin, a damaging, rejecting woman. And now it was Mac who thought she didn’t want to see him again, because she had more or less told him so. He hadn’t called in over a week. Maybe he had given up on her.

The way my father gave up on me, Polly thought.

The interviews are finished now; I could go to Key West. I could take a chance, I could do it, she thought, taking in a breath and holding it. But it wouldn’t be easy. She sighed, imagining all the anger and trouble she would bring on herself: the scenes, the explanations, the packing; trying to rent the apartment (Jeanne and Betsy would want it, but could they afford it?), telling Jim and her mother and the people at the Museum and everyone else she knew. All of them would think Polly had freaked out. Leaving a promising career, running off to Florida just like Lorin Jones,

and

with the same man — wasn’t that really kind of weird and sick? everyone would say. She starts writing about Jones, and ends up living Jones’s life, for God’s sake! They wouldn’t expect it to work out, and maybe they would be right.

But if she didn’t try it, how could she ever be sure?

“And when you finish your book, what then?” her friends would ask.

Well, she would say, I’ll just have to see. Maybe Stevie and I will come back to New York. Or maybe we’ll stay in Key West for a while, living on the rent of this apartment and Stevie’s child support. Maybe I’ll get a job in a local gallery or something.

It wouldn’t be all tropical flowers. She would be a middle-aged dropout like Mac, living a marginal life in a beach resort; she would probably never be well off or well known.

But no matter what happened afterward, I would be with him now, Polly thought, taking a great gasping breath of air as if she had just come up from underwater. I could write the book the way it ought to be. And I could start painting again if I wanted to. Even if it wasn’t any good at first, it might get better. As Mac said, you never know; I might strike it lucky one day. And if everything worked out — It was crazy even to think of it, probably, but if I really wanted to I could have another child.

Polly looked at her watch. Half-past five. It was fully dark out now, and would probably be dark in Key West too, though the sun set later there. Mac and his crew would have finished work, and he would have gone back to the room he was renting from friends.

Before she could lose her nerve, or change her mind again, she ran toward the kitchen. She stared at the harmless-looking wall telephone for a second, took a final deep breath, and picked up the receiver.

Alison Lurie (b. 1926) is a Pulitzer Prize–winning author of fiction and nonfiction. Born in Chicago and raised in White Plains, New York, she grew up in a family of storytellers. Her father was a sociology professor and later the head of a social work agency; her mother was a former journalist. Lurie graduated from Radcliffe College, and in 1969 joined the English department at Cornell University, where she taught courses on children’s literature, among others.

Lurie’s first novel,

Love and Friendship

(1962), is a story of romance and deception among the faculty of a snowbound New England college. It won favorable reviews and established her as a keen observer of love in academia. Her next novel,

The Nowhere City

(1965), records the confused adventures of a young New England couple in Los Angeles among Hollywood starlets and Venice Beach hippies. She followed this with

Imaginary Friends

(1967), which focuses on a group of small-town spiritualists who believe they are in touch with extraterrestrial beings.

Her next novel,

Real People

(1969), led the

New York Times

to call her “one of our most talented and intelligent novelists.” The tale unfolds in a famous artists’ colony where much more than writing and painting occurs. Lurie then returned to an academic setting with her bestseller

The War Between the Tates

(1974), and drew on her own childhood in

Only Children

(1979). Four years later she published

Foreign Affairs

, her best-known novel, which traces the erotic entanglements of two American professors in England. It won the Pulitzer Prize in 1985.

The Truth About Lorin Jones

(1988) follows a biographer around the United States as she searches for the real, and sometimes shocking, story of a famous woman painter —a character who appears as an eight-year-old in

Only Children. The Last Resort

(1999) takes place in Key West, Florida, among a group of ill-assorted characters, some of who appear in earlier Lurie novels.

Truth and Consequences

(2005) returns to an academic setting and plumbs the troubles of a professor with back trouble, his exhausted wife, and two poets — one famous and one not.

Lurie has also published a collection of semi-supernatural stories,

Women and Ghosts

(1994), and a memoir of the poet James Merrill,

Familiar Spirits

(2001). Her interest in children’s literature inspired three collections of folktales, including

Clever Gretchen

(1980), which features little-known stories with strong female heroines. She has published two nonfiction books on children’s literature, as well:

Don’t Tell the Grown-ups

(1990) and

Boys and Girls Forever

(2003). In the lavishly illustrated

The Language of Clothes

(1981), she offers a lighthearted study of the semiotics of dress.

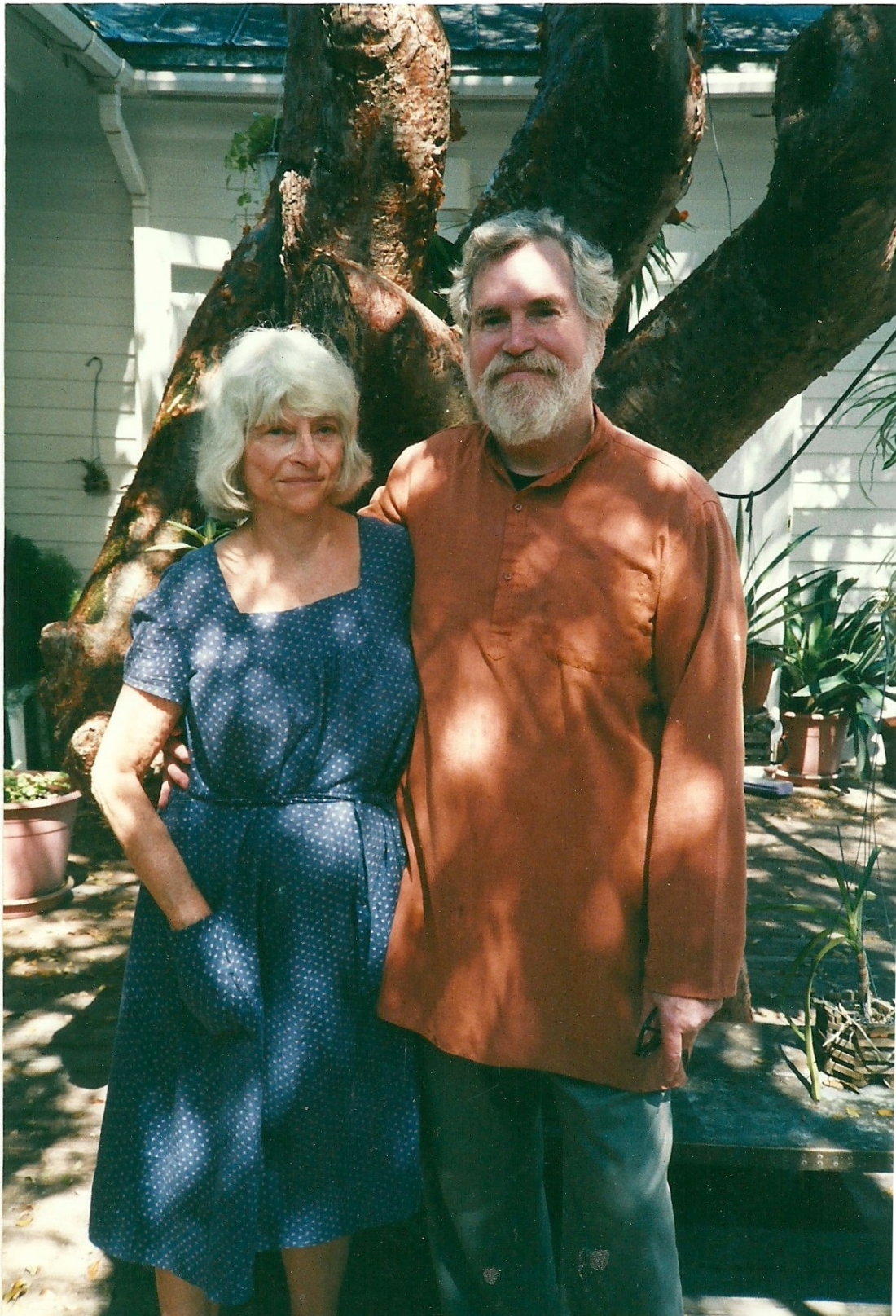

Lurie officially retired from Cornell in 1998, but continues to teach and write. In 2012 she was named to a two-year term as the official New York State Author. She lives in Ithaca, New York, and is married to the writer Edward Hower. She has three grown sons and three grandchildren.

Lurie at age seven.

Lurie at age fourteen, wearing her first long party dress in preparation for dancing school.

Lurie and her dog, Sliver, in the backyard of her family’s home in White Plains, New York, in the summer of 1947. (Photo courtesy of Kroch Library.)

Lurie on the porch of her parents’ home in White Plains, New York, in the early spring of 1947.