The Turner House

Authors: Angela Flournoy

Swelling Bellies and Wedding Tulle

A Prudent Wife Is from the Lord

Copyright © 2015 by Angela Flournoy

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Flournoy, Angela.

The Turner house / Angela Flournoy.

p. cm

ISBN

978-0-544-30316-4 (hardback)â

ISBN

978-0-544-30320-1 (ebook)

1. African American familiesâFiction. 2. Domestic fiction. 3. Historical fiction. I. Title.

PS3606.L6813T87 2015

813'.6âdc23

2014034423

v1.0415

A portion of this novel appeared, in different form, in

The Paris Review.

“They Feed They Lion,” copyright © 1968, 1969, 1970, 1971, 1972 by Philip Levine; from

They Feed They Lion and the Names of the Lost: Poems

by Philip Levine. Used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

For my parents,

Francine Dunbar Harper

and Marvin Bernard Flournoy,

for being real

In loving memory of Ella Mae Flournoy,

who saw more than I can make up

and loved more than I can imagine

The Negro offers a feather-bed resistance. That is, we let the probe enter, but it never comes out. It gets smothered under a lot of laughter and pleasantries.

âZora Neale Hurston,

Mules and Men

Out of the gray hills

Of industrial barns, out of rain, out of bus ride,

West Virginia to Kiss My Ass, out of buried aunties,

Mothers hardening like pounded stumps, out of stumps,

Out of the bones' need to sharpen and the muscles' to stretch,

They Lion grow.

âPhilip Levine, “They Feed They Lion”

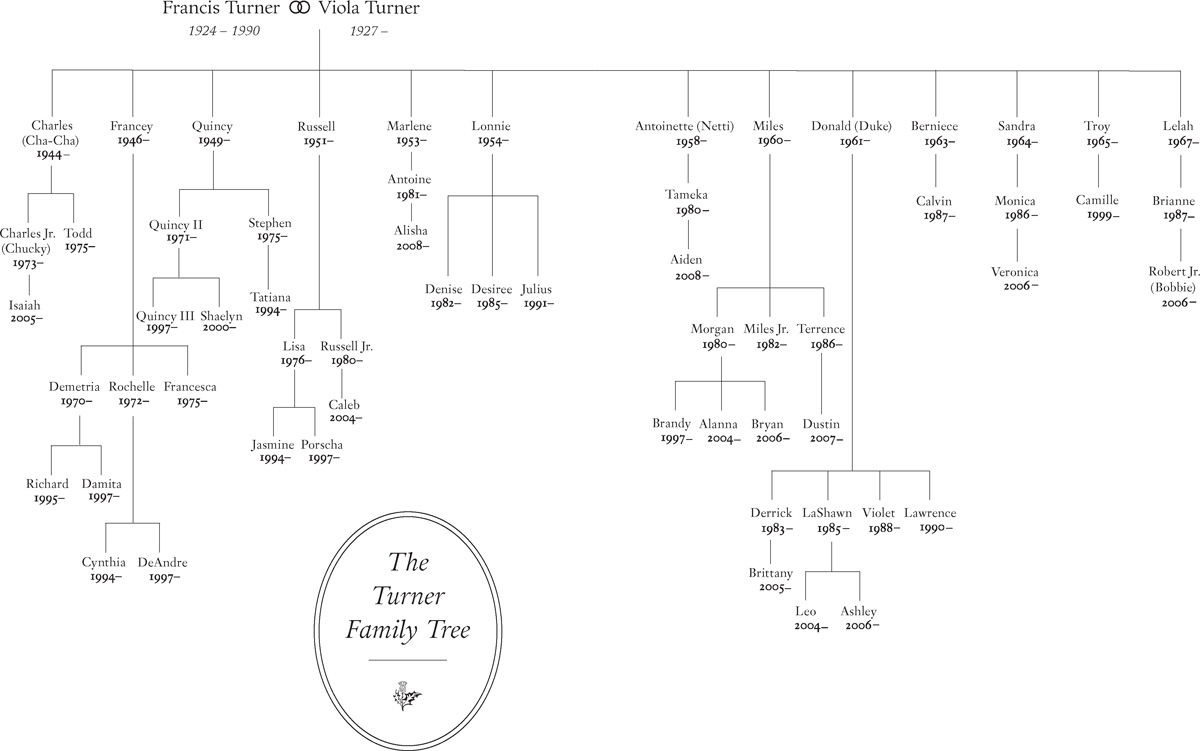

The eldest six of Francis and Viola Turner's thirteen children claimed that the big room of the house on Yarrow Street was haunted for at least one night. A ghostâa haint, if you willâtried to pull Cha-Cha out of the big room's second-story window.

The big room was not, in actuality, very big. Could hardly be considered a room. For some other family it might have made a decent storage closet, or a mother's cramped sewing room. For the Turners it became the only single-occupancy bedroom in their overcrowded house. A rare and coveted space.

In the summer of 1958, Cha-Cha, the eldest child at fourteen years, was in the throes of a gangly-legged, croaky-voiced adolescence. Smelling himself, Viola called it. Tired of sharing a bed with younger brothers who peed and kicked and drooled and blanket-hogged, Cha-Cha woke up one evening, untangled himself from his brothers' errant limbs, and stumbled into the whatnot closet across the hall. He slept on the floor, curled up with his back against dusty boxes, and started a tradition. From then on, when one Turner child got grown and gone, as Francis described it, the next eldest child crossed the threshold into the big room.

The haunting, according to the older children, occurred during the very same summer that the big room became a bedroom. Lonnie, the youngest child then, was the first to witness the haint's attack. He'd just begun visiting the bathroom alone and was headed there when he had the opportunity to save his brother's life.

Three-year-olds are of a tenuous reliability, but to this day Lonnie recalls the form of a pale-hued young man lifting Cha-Cha by his pajama collar out of the bed and toward the narrow window. Back then a majority of the homeowners in that part of Detroit's east side were still white, and the street had no empty lots.

“Cha-Cha's sneakin out! Cha-Cha's sneakin out with a white boy!” Lonnie sang. He stamped his little feet on the floorboards.

Soon Quincy and Russell spilled into the hallway. They saw Cha-Cha, all elbows and fists, swinging at the haint. It had let go of Cha-Cha's collar and was now on the defensive. Quincy would later insist that the haint emitted a blue, electric-looking light, and each time Cha-Cha's fists connected with its body the entire thing flickered like a faulty lamp.

Seven-year-old Russell fainted. Little Lonnie stood transfixed, a pool of urine at his feet, his eyes open wide. Quincy banged on his parents' locked bedroom door. Viola and Francis Turner were not in the habit of waking up to tend to ordinary child nightmares or bed-wetting kerfuffles.

Francey, the eldest girl at twelve, burst into the crowded hallway just as Cha-Cha was giving the haint his worst. She would later say the haint's skin had a jellyfish-like translucency, and the pupils of its eyes were huge, dark disks.

“Let him go, and run, Cha-Cha!” Francey said.

“He ain't runnin me outta here,” Cha-Cha yelled back.

With the exception of Lonnie, who had been crying, the four Turner children in the hallway fell silent. They'd heard plenty of tales of mischievous haints from their cousins Down Southâthey pushed people into wells, made hanged men dance in midairâso it did not follow that a spirit from the other side would have to spend several minutes fighting off a territorial fourteen-year-old.

Francey possessed an aptitude for levelheadedness in the face of crisis. She decided she'd seen enough of this paranormal beat-down. She marched into Cha-Cha's room, grabbed her brother by his stretched-out collar, and dragged him into the hall. She slammed the big-room door behind them and pulled Cha-Cha to the floor. They landed in Lonnie's piss.

“That haint tried to run me outta the room,” Cha-Cha said. He wore the indignant lookâeyebrows raised, lips partedâof someone who has suffered an unbearable affront.

“There ain't no haints in Detroit,” Francis Turner said. His children jerked at the sound of his voice. That was how he existed in their lives: suddenly there, on his own time, his quiet authority augmenting the air in a room. He stepped over their skinny brown legs and opened the big room's door.

Francis Turner called Cha-Cha into the room.

The window was open, and the beige sheets from Cha-Cha's bed hung over the sill.

“Look under the bed.”

Cha-Cha looked.

“Behind the dresser.”

Nothing there.

“Put them sheets back where they belong.”

Cha-Cha obliged. He felt his father's eyes on him as he worked. When he finished, he sat down on the bed, unprompted, and rubbed his neck. Francis Turner sat next to him.

“Ain't no haints in Detroit, son.” He did not look at Cha-Cha.

“It tried to run me outta the room.”

“I don't know what all happened, but it wasn't that.”

Cha-Cha opened his mouth, then closed it.

“If you ain't grown enough to sleep by yourself, I suggest you move on back across the hall.”

Francis Turner stood up to go, faced his son. He reached for Cha-Cha's collar, pulled it open, and put his index finger to the line of irritated skin below the Adam's apple. For a moment Cha-Cha saw the specter of true panic in his father's eyes, then Francis's face settled into an ambivalent frown.

“That'll be gone in a day or two,” he said.

In the hallway the other children stood lined up against the wall. Marlene, child number five and a bit sickly, had finally come out of the girls' room.

“Francey and Quincy, clean up Lonnie's mess, and all y'all best go to sleep. I don't wanna hear nobody talkin bout they tired come morning.”

Francis Turner closed his bedroom door.

The mess was cleaned up, but no one, not even little Lonnie, slept in the right bed that night. How could they, with the window curtains puffing out and sucking in like gauzy lungs in the breeze? The children crowded into Cha-Cha's roomâa privileged first visit for most of themâand retold versions of the night's events. There were many disagreements about the haint's appearance, and whether it had said anything during the tussle with Cha-Cha. Quincy claimed the thing had winked at him as he stood in the hallway, which meant that the big room should be his. Francey said that haints didn't have eyelids, so it couldn't have winked at all. Marlene insisted that she'd been in the hall with the rest of them throughout the ordeal, but everyone teased her for showing up late for the show.

In the end the only thing agreed upon was that the haint was real, and that living with it was the price one had to pay for having the big room. Everyone, Cha-Cha included, thought the worry was worth it.

Like hand-me-down clothes, the legacy of the haint faded as the years went by. For a few years the haint's appearance and Cha-Cha's triumph over it remained an indisputable, evergreen truth. It didn't matter that no subsequent resident of the big room had a night to rival Cha-Cha's. None of them ever admitted to hearing so much as a tap on the window during their times there. The original event was so remarkable that it did not require repetition. Cha-Cha took on an elevated status among the first six children; he had landed a punch on a haint and was somehow still breathing. But with each additional child who came along the story lost some of its luster. By the time it reached Lelah, the thirteenth and final Turner child, Francis Turner's five-word rebuttal, “Ain't no haints in Detroit,” was more famous within the family than the story behind it. It first gained a place in the Turner lexicon as a way to refute a claim, especially one that very well might be trueâa signal of the speaker's refusal to discuss the matter further. The first six, confident that Francis Turner secretly believed in the haint's existence, popularized this usage. By Lelah's youth, the phrase had mutated into an accusation of leg pulling:

“Daddy said if I get an A in Mrs. Paulson's, he'd let me come on his truckin trip to Oregon.”

“Or-e-gone? Come on, man. Ain't no haints in Detroit.”

Cha-Cha transported Chryslers throughout the Rust Belt on an eighteen-wheeler. The job was the closest thing to an inheritance that he received from his father. After his twenty-fifth birthday the old man took him to his truck yard, introduced him to the union boss, and ushered him into the world of eighteen-wheelers, all-nighters to Saint Louis, and the constant, cloying smell of diesel fuel. Cha-Cha joked with his brothers who'd joined the service that he was more decorated at Chrysler than all of them combined. This wasn't a warmly received joke, but it was true. He held records in the company for fewest accidents, best turnaround times, cleanest cab, leadership, and dependability. He did this for over three decades, until, if what he saw was really what he thought he saw, the haint tried to kill him.