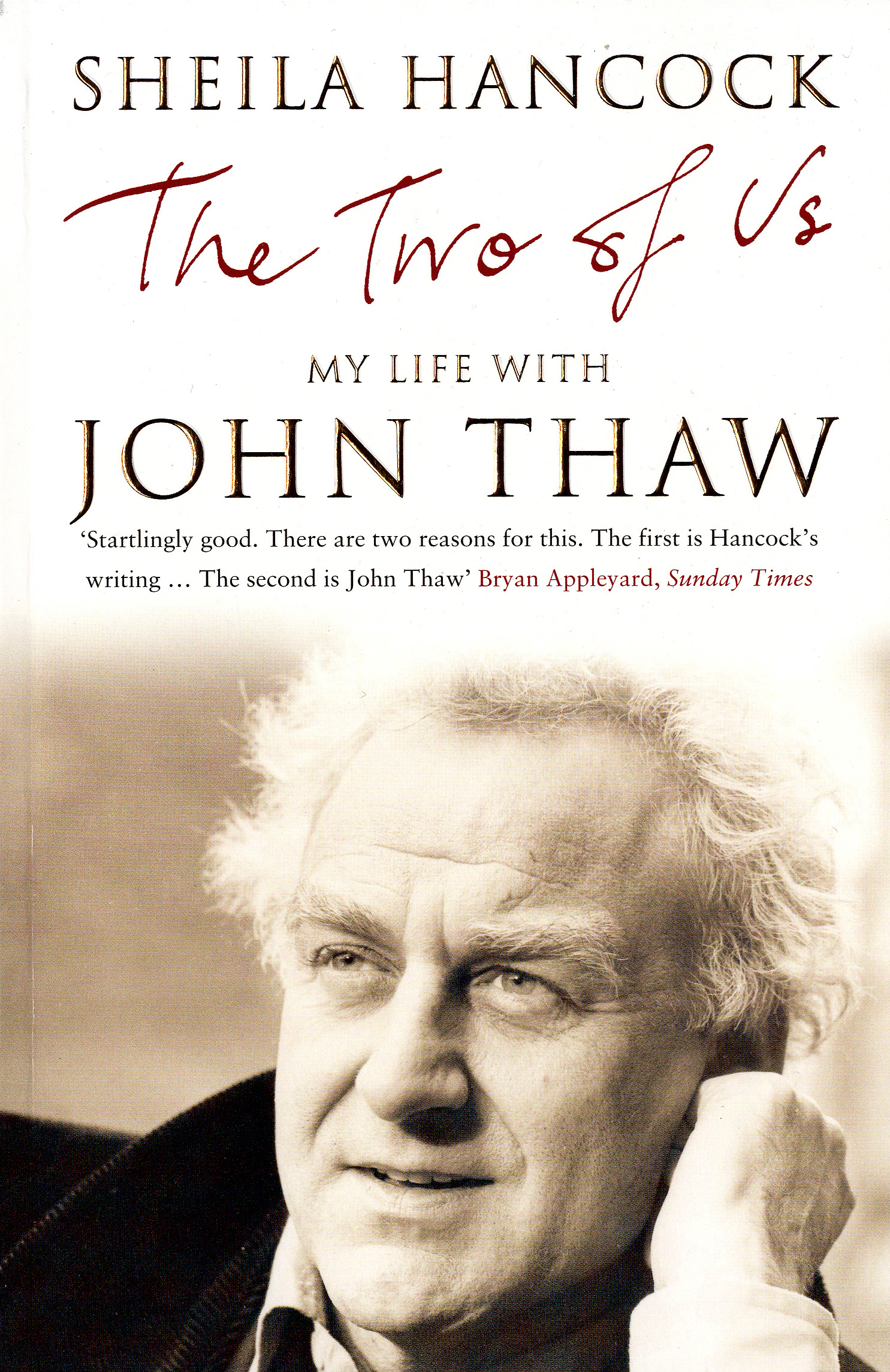

The Two of Us

Authors: Sheila Hancock

THE TWO OF US

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Ramblings of an Actress

THE TWO OF US

My Life with John Thaw

SHEILA HANCOCK

First published in Great Britain 2004

Copyright © Sheila Hancock

This electronic edition published 2009 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

The right of Sheila Hancock to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 36 Soho Square, London W1D 3QY

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 978-1-40880-693-7

www.bloomsbury.com/sheilahancock

Visit

www.bloomsbury.com

to find out more about our authors and their books.

You will find extracts, authors interviews, author events and you can sign up for newsletters to be the first to hear about our latest releases and special offers.

When Clare Venables was dying, her friend Peter Thompson wrote her this letter.

My much-loved friend,

It matters to have trodden the earth proudly, not arrogantly, but on feet that aren’t afraid to stand their ground, and move

quickly when the need arises. It matters that your eyes have been on the object always, aware of its drift but not caught

up in it. It matters that we were young together, and that you never lost the instincts and intuitions of a pioneer. It matters

that you have been brave when retreat would have been easier. It matters that, in many places and at many times, you have

made a difference. Your laugh has mattered. Your love has mattered. Above all, it matters that you have been loved.

Nothing else matters.

The sentiments he expresses apply equally to my husband John Thaw. I borrow them in dedicating this book to them both.

I also wish to pay tribute to John’s brother Ray, who died in June 2004.

It takes two.

I thought one was enough,

It’s not true;

It takes two of us.

You came through

When the journey was rough.

It took you.

It took two of us.

It takes care.

It takes patience and fear and despair

To change.

Though you swear to change,

Who can tell if you do?

It takes two.

– ‘It Takes Two’ from

Into the Woods

by

Stephen Sondheim

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My deepest gratitude to Alexandra Pringle, without whom this book would never have been started, and Victoria Millar, without

whose gentle guidance and advice it would certainly never have been finished.

Also thanks to many people I have interviewed to fill in the gaps in my knowledge of John’s life.

Some of the proceeds of this book will go to The John Thaw Foundation which aids young people who need a helping hand.

The John Thaw Foundation

PO Box 38848

London

W12 9XN

3 September 2000

Walking in our field. A soft mist of rain. The sun shining

behind the drizzle. A rainbow forms across the sky behind

me. It reflects in the raindrops on grass and trees. Millions

of multicoloured baubles, iridescent, extraordinary.

John, quick, come and look.

Racing back over the wooden bridge, into the conservatory,

I toss aside his script, grab his hand and pull him,

limping and protesting, to my magic vision.

It’s gone.

Oh, great. Miserable wet trees, pissing rain and soaking

wet trouser legs – thanks a bunch.

But it was beautiful.

Well, you daft cow, why didn’t you stay and enjoy it?

I couldn’t enjoy it properly without you.

Oh, come ’ere, Diddle-oh.

Arms pulling me tight, hands on bum, wet faces nuzzling,

laughing. An aging man and woman, happy in a wet field.

You should have known it wouldn’t last, kid.

He meant the rainbow.

26 January 2001

Been asked to do the narration in a recording of a musical

version of Peter Pan at the Festival Hall. Was playing a

demo of the score, which is charming, when I noticed John

lurking.

I, THE GIRL, Sheila Cameron Hancock, was born on the Isle of Wight on 22 February 1933, nine years before him. He, the boy,

John Edward Thaw, was born in Manchester on 3 January 1942. The intrusion of World War II was not the only similarity in our

childhoods. Varying degrees of fear, abandonment and delight were common moulding influences. As was a performance of

Where the Rainbow Ends

, a musical play for children about St George’s quest to slay the dragon.

As the girl was the first to arrive, we’ll start with her.

When I was three years old I sat entranced in the Holborn Empire watching a beautiful sprite called Will o’ the Wisp floating

about on rainbow-coloured wings. When my mummy whispered that it was my sister Billie leading Uncle Joseph to the end of the

rainbow I absolutely believed in magic, because I could see it there, in front of me, on this enchanted place called a stage.

So dumbfounded was I by my sister’s transformation that I had a massive nosebleed. I refused to leave, preferring to ruin

the cotton hankies of half the audience in the dress circle. People didn’t use tissues in those days.

My father worked for the brewery, Brakspeare Beers, that put him and my mother into various pubs and hotels around the country

as managers. They were working at the Blackgang Hotel on the Isle of Wight when I was born. Its windswept Chine, with the

skeleton of a whale in the garden, looks pretty bleak in photos.

We moved directly after my birth so I remember nothing of it, but my parents told tales of smugglers and incest in that cutoff

part of the island. My seven-year-old sister lived in dread of the adders that infested the garden and of the cliff adjacent

to the hotel crumbling into the sea, as it often did. Now the Chine is a rip-roaring amusement centre, but in 1933 it can’t

have been a very jolly place from which to greet the world.

After a brief spell in Berkshire we landed up in a spit and sawdust pub called The Carpenter’s Arms in King’s Cross. We lived

in the flat above the bars. It reeked of stale beer and the whole place shook and glasses rattled as trains passed the backyard.

Sleep was not easy. I was often still awake when Dad shouted, ‘Time, gentlemen, please,’ hoping that the shouts on the pavement

outside would not be accompanied by too much breaking glass and thuds and screams. The jollity was equally raucous. I was

not allowed into the public or saloon bars, or Dad might lose his licence, so I sat on the stairs leading up to our quarters,

listening to the adults letting loose. Mummy played the piano for Daddy to sing ‘The Road to Mandalay’ and then both of them

silenced the babble with:

If you were the only girl in the world

And I were the only boy

Nothing else would matter in this world today

We would go on loving in the same old way

A garden of Eden just made for two

With nothing to mar our joy.

I would say such wonderful things to you

There would be such wonderful things to do

If you were the only girl in the world

And I were the only boy.

I too entertained the customers. Fired by my sister’s triumph in

Rainbow

, I regularly performed the whole of

Snow White

and the Seven Dwarfs

, playing all the roles to the captive audience of women hoping for a quiet port and lemon in the Ladies’ Bar.

27 January

Remembering John’s addiction to Sondheim’s

Sweeney Todd

when I was in it at Drury Lane and wondering if he

might enjoy a break from telly coppers and lawyers, I played

a Captain Hook number while he was in earshot. It’s good.

Funny-scary.

‘You could do that.’

‘Nah.’ But he twinkled a bit.

My first school was St Ethelreda’s Convent in Ely Place in Holborn. I am not a Catholic, yet I learned my Catechism and all

the rules and regulations like a good little child of the faith. I could not abide the smell of incense though. The nuns did

their best to save my soul but I retched and went green whenever the priest shook his thurible anywhere near me, and eventually

I was allowed to sit with the nuns behind a glass screen at the back of the chapel, watched from the pews by my mortified

sister.

There was plenty for the nuns to pray for. Alarming things were happening in Hitler’s Germany. In 1932 Broadcasting House

had opened its impressive new quarters in Langham Place. Inside was a mural declaring, ‘Nation Shall Speak Peace Unto Nation’.

The message eluded Adolf Hitler. In 1933, the year of my birth, he became Chancellor of Germany and after a suspicious fire

at the Reichstag, used the excuse of a Communist threat to prevent freedom of speech, burn books and forbid public assembly.

His spin doctor, Goebbels, took over the airwaves. His message was not one of peace. Ethnic cleansing had begun. Dachau had

opened, Jewish shops were being boycotted, and rumours of a programme of sterilisation of disabled people in Germany were

circulating. In 1936 only a few token Jews were allowed to take part in the German Olympic Games and Hitler refused to shake

hands with the winning black athlete, Jesse Owens. Closer to home there were Fascist rallies in London led by Oswald Mosley,

vigorously opposed by some of our friends and neighbours.

My family history is a bit vague, but there were several related Cohens that we visited in Lewisham and a photo of a portrait

of a crinolined woman who I was told was a relative called Madame Louisa Octavia Zurhorst. She reputedly fled Prussia from

an earlier pogrom. My mother lost a Polish fiancé in 1917 and both my parents had their youth blighted by the horrors of that

war to end wars. The signs of more trouble from Germany must have alarmed them.

29 January

A gentleman called Mohammed Wali, the Taliban religious

police minister, has forced Hindus in Afghanistan to wear

labels. Oh dear.

Life in King’s Cross for a child innocent of Jarrow marches and nasty Nazis was bliss. Every Sunday morning I donned my best

dress with matching apron, made by my mum, and collected a pint of winkles and shrimps for our tea from the barrow on the

corner. I laboriously took off all the hard brown lids with my pin and then twisted the grey morsels from their shells, competing

with my dad to get a winkle out intact. I lingered to sing jolly hymns with the Salvation Army band outside the pub, sometimes

bashing a tambourine, and sat on the stoop with my fizzy lemonade and a bag of crisps with a twist of salt in blue paper inside.

From the door, I watched the Salvation girls in their bonnets collecting from the respectful customers and helped them count

the money in their little velvet bags. On Sunday afternoon there was the Walls ice-cream man, ringing the bell on his tricycle

with a square box in front full of goodies. The lip-licking choice between a triangular water ice, a small drum wrapped in

paper to peel and put in a cone, or a wrapped flat brick with a couple of wafers to make a sandwich was a very serious matter.

Food seems to feature prominently in my memories and probably accounts for the somewhat chubby child in the very few photos

I have of myself then and for my father’s nickname for me: Bum Face. When I got older and thinner, Bum Face alternated with

the then more accurate nickname Skinny Lizzy or, mysteriously, Lizzy Dripping.

The Royal Family were central to our lives. At any royal occasion we were there cheering among the crowds, me heaved on to

my dad’s shoulders for a better view, and after the procession, rushing down the Mall hoping for a balcony appearance. I did

not realise that the enthusiasm of the crowd at the Coronation of George VI in 1937 was fuelled by their confusion at the

abdication of the Duke of Windsor, but I was thrilled that there were now two little girls in the new Royal Family. I loved

the diamonds and pretty frocks and golden coaches. Life was colourful and exciting for a child. It was accepted that some

of our customers were dodgy but the police from the station over the road kept an eye on things. There was a code of behaviour

among villains that protected my parents from harm. When a drunk smashed a glass with the intention of jabbing it in my mother’s

face, the local gang leaped on him and made sure he never entered the pub again.

My parents worked long hours. When the pub was closed my mum cleaned, washed glasses and prepared bar snacks, and Dad did

his complicated work among the wooden barrels in the dank cellar. It involved thermometers and little brass buckets for slops.

And quite a bit of tasting. Up in the bar too Dad began to respond more often in the affirmative to ‘Have one yourself, Rick.’

Often he would make it a short. Eventually, he or the brewery or, more likely, my mum, decided he should try another career.

In 1938 they left the pub life and moved to the suburbs.

31 January

Today John was persuaded to go over a couple of numbers

with the musical team for

Peter Pan.

He was, of course,

sensational. The bastard. Is there nothing he can’t do when

he sets his mind to it? The result is he is going to offer

the world, leastways Radio 3, his all-singing, all-dancing

Captain Hook. Joanna is on board testing her versatility by

playing sundry pirates, mermaids and Tiger Lily so it’s a

Thaw show.

After the rough and tumble of King’s Cross, Bexleyheath in Kent seemed dreadfully dull. My parents thought it was a step up

to have a home separate from their work, which they were buying on the never-never. It was an entirely new concept for people

like them to own their own home – eventually. Everyone’s ambition was to have a detached house and we were on our way with

a semi. A long street of identical pebble-dashed: two beds, boxroom, bathroom and, great luxury, separate loo, upstairs, and

two rooms and kitchenette downstairs. In the garden was a shed where I helped my dad make and repair broken furniture, holding

planks of wood in the clamp while he sawed them, and stirring the glue bubbling in the black iron pot. Maybe the fumes from

it contributed to my elation. Every day I laid out his brushes and yellow dusters and opened the tins for the daily shoe-cleaning

ritual. I was barred from the shed before Christmas when Dad did secret things there. The anticipation was thrilling as he

sneaked furtively out of the shed and made a great show of locking the door. As well as the apple and orange in my sock, I

would find at the foot of my bed a jewel box or a wooden puppet, and, one extra specially exciting year, a sewing box on legs

lined with quilted pink satin, left over from their newly made eiderdown, and equipped with needles, cottons and a thimble

and scissors just like Mum’s.

All the houses in Latham Road had identical gardens back and front and there were – very much admired, this – little sticks

along the pavement that would grow into cherry trees. We had definitely gone up in the world. We left behind a life of beer

and skittles or, in the case of The Carpenter’s Arms, shove-halfpenny and darts, and became lower-middle-class. Dad got a

job at the Vickers factory in Crayford and Mum worked in a family-owned store called Mitchells of Erith. It was a sedate emporium

where my enterprising mother worked her way up from gloves through lingerie to setting up a little café and theatre booking

office in the shop.

In their free time my parents set about transforming the house to show we were not going to be swallowed up into conformity.

I aided my father in building a mini Tivoli Gardens in front of the house, using an antique stone bird-bath as a centre-piece.

He and I nicked it by dead of night from a derelict house, a provenance my father was never quite comfortable with. The garden

had irregular flower beds and a sunken crazy-paved area.