The Various (5 page)

Authors: Steve Augarde

Chapter Three

MIDGE WANTED TO

run. The back of her neck felt cold and tight and prickly, and she wanted to run and run, back down the hill, flying and flying as fast as ever she could. Her legs weren’t moving though. She was aching to run, but her legs weren’t moving. She was still standing by the gap in the barn door, and she was clutching her carrier bag tightly. The sound of the voice, strange and foreign, had made her whole body lock tight, rigid. Eventually she realized that her neck was hurting and she somehow managed to let her shoulders drop. She moved her head slightly, and shifted her balance. Now she knew that she could run, if she wanted to. Yet she remained, listening at the door. Then another sound came from the warm darkness of the barn – and it

was

from the barn this time. There were no words, just a gasp. A gasp of pain, and despair and utter defeat.

Midge suddenly stopped feeling frightened. Something in that terrible despairing sound drove her fear away, and made her feel that she must do something to help. Whoever was behind that door was in

real

trouble. She dropped her carrier bag again and caught hold of the metal grab-handle on the door, pulling it to one side in order to slide it across. The door

wouldn’t

slide though. It moved backwards and forwards just a little, but she couldn’t make it slide open. Something was stopping it. She stepped back and looked up. There was a kind of metal runner on the top of the frame and she could see that the door was supposed to hang on this, rolling backwards or forwards on two small wheels. One of the wheels had come out of the runner, and that was why the door was hanging at a crooked angle. She would have to try and lift one side up and hook the wheel back into its place. The door was big and she didn’t see how she could manage this, but she tried. She found that she could barely raise the side of the door that was hanging down; she certainly didn’t have the strength to manoeuvre the wheel back into its runner at the same time. It was hopeless. Gasping now, desperate to help, all her fear forgotten, she ran around the outside of the barn, looking for another entrance. There wasn’t one. The sliding door was the only way in. Midge was close to tears. Should she run for help after all? She looked around for inspiration.

There was a rusty roll of pig-wire round the back of the barn, and an old tin bath with a little pool of green water in it. Nothing that was of any use to her, as far as she could see. Next to the dripping tap at the side of the building, however, lay half a dozen wooden fencing posts. They had sharp points. The ones at the bottom had rotted from lying on the damp concrete,

but

the top ones looked OK. Midge picked one up, with no clear notion of what she would do with it, and carried it round to the front of the barn, accidentally banging it against the corner of the building as she did so, and feeling the sharp prick of a splinter going into her thumb as she struggled not to drop the thing. The idea came to her that she might be able to use the post as a lever, or perhaps use it to hook the wheel back into place somehow. She managed to wriggle the pointed end of the post under the door and heave it upwards. The door creaked, and was raised momentarily, but she still couldn’t get the wheel to go back into its runner. After a couple of attempts, however, she found that if she lifted the post and pulled it sideways she could make the door move sideways a little, too. Bit by bit, and with a lot of heaving and struggling, she managed to lift and jiggle the door across until there was a big enough gap for her to be able to get through. By this time she was out of breath and her hands were sore and scratched, but she was pleased with what she’d done. She stood by the entrance, hesitant once more, and tried to look into the barn without actually crossing the threshold.

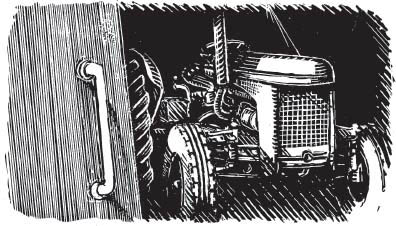

Directly in front of her, where the light fell through the doorway, she could see the front of a grey tractor. The radiator grille was all cobwebby and tilted to one side slightly – one of the tyres was flat. Midge slowly put her head in through the doorway to try and see more.

‘Where are you?’ she said quietly. A rustle and another gasp of pain came from the darkness, making

her

jump back yet again. The sound had come from the furthest corner of the barn. She looked nervously in once more, but couldn’t see a thing. ‘Shall I get help?’ She was almost whispering now. There was a smell, not pleasant – an animal smell of dung and ammonia. Another sharp gasp of breath from the darkness, then the voice – and once more the words seemed to appear from somewhere inside her.

No!

A pause.

You . . . help . . . me. You!

Midge stood her ground this time, but again her first reaction was to put her hands up to her ears. The voice frightened her. It was as though someone was talking to her on a strange kind of telephone. A telephone inside her head. She could hear the words, she could see them somehow, like pictures, like colours, and yet there was no sound in the air. The accent was foreign, or unusual at any rate, and the voice seemed distant – not human. It wasn’t her own voice, she was sure of that. Was she dreaming?

Her left thumb hurt, but she was too frightened to look at it – too frightened to look away from the darkness inside the barn. Finally she managed to pluck up enough courage to creep slowly forward.

She shuffled to the left, once she was through the doorway, and edged along the wall a little so that she was no longer blocking the light. The tips of her fingers brushed the cool roughness of the concrete behind her. She moved forwards slightly. Now she could see more. In the furthest corner of the building she could make out a piece of farm machinery. It had several large spiky wheels – like spiders’ webs or

Catherine

wheels – which were overlapping, the spokes slightly bent in a crooked regular pattern. The wheels were pale yellow, or so they seemed in the dimness of the barn, and were mounted on a heavy red frame. Some kind of raking machine? A sudden movement beneath the frame made her jump back against the wall, and again she was ready to run. That’s where it was! Lying beneath the machine! It looked like – a bundle of rags or sheets, whitish, something flapping. Midge glanced back at the doorway, reassuring herself that she could flee at a moment’s notice, then edged away from the wall, and crept slowly towards the machine, her heart bumping. More movement! She stopped. She could see – what? A leg? Legs. The pale limbs of some creature, an animal, skinny, like a greyhound or a small deer. Was it a deer? A white deer? The game she had thought of playing suddenly came back to her – hunting the hart in the Royal Forest. Was it a white hart? No. But this was too

weird

. And what about the voice? She was frightened again, thinking that there must be someone else in the barn besides her and . . . whatever was lying there. She looked around, but could see nothing, nobody else. What

was

it?

Aaach!

Another groan and more flapping of the sheet, or whatever the creature was tangled up in. Midge caught the flash of what looked like a tiny hoof, delicate, familiar, but so small . . . well it certainly wasn’t a dog at any rate. She could make out a pale belly heaving, slim legs, bits of . . . cloth, maybe, flapping. Hair, long matted hair. But no head. Where was its head? It still made no sense. She crept closer . . .

Spick! Spickitspickitspickit!

Midge felt her heart bounce up into her throat, and once more the cold prickly feeling shot up the back of her neck. She knew now that there was nobody else in the barn. There was no doubt that the voice came from . . . whatever that thing was. Whatever it was – and it was certainly an animal – it had a voice. But the

sound

of the voice was in her head.

It was moving again – some other part, something that had been hidden, was moving. The tangled mess of a creature, covered in dung, bloodstained, trapped and exhausted, seemed somehow to unravel itself. Slowly and painfully, it lifted its head. Midge stood, unable to move, eyes wide open in disbelief. It was a horse. It

couldn’t

be – and yet it was . . . though like no horse she had ever seen before. Tiny, slenderly built, not much bigger than a baby deer after all, it nevertheless appeared to be full-grown. A small white horse.

The

head, fine and delicate but streaked with muck and sweat, turned slowly in Midge’s direction. Its silvery mane was caked and clagged with blood, and its expression was one of absolute anguish. The dark eyes, deep and glistening with pain, looked directly at Midge as she stood in the middle of the barn floor, her mouth open, transfixed. A long moment passed as they stared at each other.

Then the horse spoke to her, and Midge felt her knees begin to buckle. She almost fell. The voice, dry and croaking, thickly accented, seemed to enter her mind from another world. There was no sound in the still foetid atmosphere of the barn, yet the words were as clear to her as if they had been spoken closely into her ear, as clear as colours on a screen – and strange beyond belief.

Help . . . me . . . maid. Some mercy . . . I beg

.

The struggling creature, elegant, beautiful even in its agony, arched its slim neck and attempted to look over its blood-streaked shoulder, indicating to Midge where the trouble lay. Midge stumbled closer, almost against her will, and the back of her hand banged across her open mouth as she did so. Now she could see clearly. At last she realized what had been causing the noise she had first heard, the frantic beating that had drawn her towards this moment. The tiny horse was skewered to the filthy concrete floor by the spiked wheels of the raking machine. The prongs had pierced straight through one of its . . . wings. The other wing flapped in the muck a couple of times, uselessly, and then ceased.

Chapter Four

THE DRIFTING SUNBEAMS

and dappled shadows gave perfect cover for Glim the archer, as he slowly moved towards his prey, among the high branches of the East Wood. A nice fat throstle – more intent on singing to the heavens above than watching out for enemies below – puffed out its speckled breast and filled the air with its morning song.

Never taking his eye off the bird, Glim felt for the shallow groove in the end of the arrow, and fitted it to the taut waxy bowstring. He drew the bow back till the knuckles of his left hand brushed against his bearded cheek. He would not miss. He was an Ickri – a hunter – and was reckoned by most to be the best archer of that tribe.

It had been a good morning’s work. Three finches and now a fine throstle, to swell the leather pecking bag that swung from his waist. The finches would go in the meat-basket to be shared by all, but the throstle he would keep. He would give it to Zelma. She would bake it in clay and it would taste good. It was rare nowadays to find such a bird, such a large bird, in the

East

Wood. There were pigeons sometimes, but the rooks and crows, the blackies and throstles, had almost disappeared. They had learned to make their homes elsewhere. Only the visitors, the little finches and swallows that came and went with the seasons, could be found here in any quantity. And with each season that passed it seemed that their numbers, too, had dwindled.

Now the summer had come at last and the times were easier, but the winter – the winter had been hard. He would not forget. The Ickri, hunters and tree-dwellers, had survived. But the tribes that dwelt on the land – the Naiad and the Wisp – had suffered. And as for those below ground, the Tinklers and the Troggles . . . well, he would not think of that this morning. They had starved, and some had died, so ’twas said. But he would not think of that. Summer was here and on this day at least, nobody would starve.

Glim spread his wings and floated down to a lower branch. A grey squirrel, sensing the hunter’s approaching shadow, broke cover and scrabbled up the trunk of a nearby ash tree, seeking the safety of the higher foliage. This was an old trick of Glim’s. Sometimes it was better to show yourself, to panic your prey into movement. Just a little movement, that was all he needed. Keeping his sharp eyes fixed on the whereabouts of the squirrel, he patiently began to climb once more.