Read The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London Online

Authors: Judith Flanders

Tags: #History, #General, #Social History

The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London (11 page)

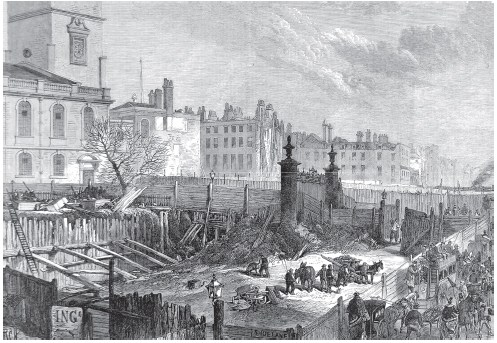

London was taking on the lineaments of modernity before its inhabitants’ eyes, although sometimes it had been hard to discern while it was happening.

3.

TRAVELLING (MOSTLY) HOPEFULLY

The technicalities of the creation of the roads, and their maintenance, were of less interest to most Londoners than how to navigate the city, and by what means. The ways to cross London evolved as rapidly as the roads had done. At the top of the tree, those with good jobs went on horseback. This required the feeding and stabling of a horse at home and also near the place of work. Only Dickens’ most prosperous characters, like the merchant prince Mr Dombey, and Carker, his second-in-command, ride to work. The playwright and journalist Edmund Yates worked for twenty-five years in the post office. As a young clerk he walked from St John’s Wood to his office behind St Paul’s: later, as he rose in the hierarchy, the combination of his increased salary, his income from playwriting, and also the fact that he was living with his mother, enabled him ‘in the summer, [to] come on horseback through the parks’. Even then, he didn’t ride all the way, paying exorbitant City livery rates. Instead he left his horse in Westminster and continued on into the City by boat.

For centuries, the Thames had been the ‘silent highway’, the major artery into London and the principal east–west transport route from one side of London to the other. At the start of the nineteenth century, it was possible to cross the river within London at only three fixed points: by London Bridge (where a crossing in some form or another had existed since Roman times), by Blackfriars Bridge (built 1769) and by Westminster Bridge (1750). There were also two wooden bridges over the river at Battersea (1771–2) and Kew (1784–9), but both were then on the very edges of London. By the time Victoria came to the throne in 1837, five new bridges had opened – Vauxhall (1816), Waterloo (1817), Southwark (1819), Hammersmith (1827,

the first suspension bridge in London) and the new London Bridge (1831, sixty yards upriver from the old location). These were later followed by Hungerford (1845), Chelsea (1851–8), Lambeth (1862), Albert and Wandsworth Bridges (both 1873) and Tower Bridge (1894), trebling the number of crossings between one end of the century and the other.

Because of the lack of crossings at the start of the nineteenth century, about 3,000 wherries and small boats were regularly available for hire to carry passengers across the river. Even in the 1830s the shore was still lined with watermen calling out, ‘Sculls, sir! Sculls!’ In

Sketches by Boz

, Mr Percy Noakes, who lives in Gray’s Inn Square, plans to ‘walk leisurely to Strandlane, and have a boat to the Custom-house’, while as late as 1840, the evil Quilp in

The Old Curiosity Shop

is rowed from where he lives at Tower Hill to his wharf on the south side of the river.

From 1815, when the

Margery

, the first Thames steamer, ran from Wapping Old Stairs to Gravesend, steamers had been used for excursion travel, and to take passengers downriver. By the early 1830s, the steamers had also become commuting boats within London, ferrying passengers between the Old Swan Pier at London Bridge and Westminster Pier in the West End, stopping along the south bank of the river at the bridges as well as at some of the many private wharves, quays and river stairs in between. (One map in 1827 showed sixty-seven sets of river stairs in the nine miles between Battersea and Chelsea in the west, and the Isle of Dogs in the east.)

Old Swan Stairs or the Old Swan Pier (the name varied; it was roughly where Cannon Street railway bridge is now) was one of the busiest landing places, the embarkation point for steamers to France and Belgium as well as the river steamers. Yet for decades it was just a rickety under-dock, reached by wooden stairs so steep they were almost ladders. Even in the 1840s, by which time it had been renamed the London Bridge Steam Wharf and had a high dock made of stone, its wooden gangway still led down to a small floating dock. Old London Bridge had been a notoriously dangerous spot on the river. The eighteen piers under the bridge, widened over the centuries to support the ageing and increasingly heavy structure, had become so large that they held back the tidal flow and created a five-foot difference in water levels between the two sides. Passengers disembarked at the Old

Swan Stairs and walked the few hundred yards to Billingsgate Stairs before re-embarking, leaving the boatmen to shoot the rapids without them. After the new London Bridge opened in 1831, for many years the steamers’ routes continued to mimic the old pattern: three steamer companies ran services above-bridge, to the west of London Bridge, and two below-bridge, to the east, with the change made at the Old Swan Stairs. In

Our Mutual Friend

, set in the 1850s, the waterman Rogue Riderhood’s boat is run down by a ‘B’low-Bridge steamer’. Long after the new bridge removed the danger, ‘steamers...dance up and down on the waves...[and] hundreds of men, women, and children, [still] run...from one boat to another’.

Hungerford Stairs was typical. Passengers walked down a narrow passage lined with advertisements ‘celebrat[ing] the merits of “

DOWN

’

S HATS

” and “

COOPER

’

S MAGIC PORTRAITS

”...We hurry along the bridge, with its pagoda-like piers...and turn down a flight of winding steps.’ On the floating pier, ‘The words “

PAY HERE

” [are]...inscribed over little wooden houses, that remind one of the retreats generally found at the end of suburban gardens’, and tickets were purchased ‘amid cries of “Now then, mum,

this way for

Cree

morne!” “Oo’s for Ungerford?” “Any one for Lambeth or Chelsea?” and [you] have just time to set foot on the boat before it shoots through the bridge.’ In

David Copperfield

, Murdstone and Grinby’s wine warehouse stood in for Warren’s blacking factory, which, until it was razed for the building of Hungerford market, had been ‘the last house at the bottom of a narrow street [at Hungerford Stairs], curving down hill to the river, with some stairs at the end, where people took boat’.

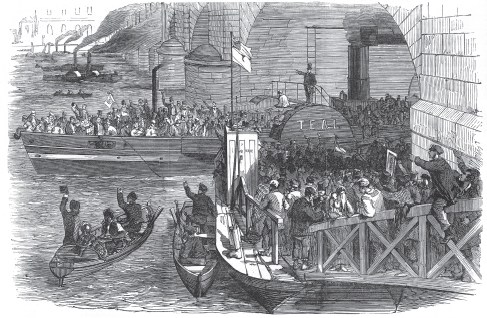

By 1837, small steamers owned by the London and Westminster Steam Boat Company shuttled between London and Westminster Bridges every day between 8 a.m. and 9 p.m., with sometimes an extension loop out to Putney in the western suburbs. Their boats, the

Azalea

, the

Bluebell

, the

Rose

,

Camellia

,

Lotus

and other floral tributes, departed every fifteen minutes, for journeys that lasted up to thirty minutes, depending on the number of intermediary stops. All but the smallest boats had hinged funnels, which folded back as they passed under the bridges. The boats were only about ten feet wide, with 18-horsepower engines and crews of five, and the boilers and the engines occupied most of the space. The skipper, wearing a top hat, stood on the bridge if there was one, or on the paddlebox itself. A call boy, ‘Quick of eye, sharp in mind, and distressingly loud in voice’, stood at the engine-room hatch and transmitted the skipper’s hand signals to the engineer below ‘with a shrillness which is a trifle less piercing than that of a steam-whistle’: ‘Sto-paw!’ (‘Stop her’), ‘E-saw!’ (‘Ease her’), ‘Half-a-turn astern!’ Because of this method of communication, signs everywhere on board warned, ‘Do not speak to the man at the wheel.’

At first it looked as though the arrival of the railways from the late 1830s would destroy this new transportation system almost before it had begun, but for the next decade the competition instead drove frequency up and fares down. By the 1840s, at least one steamer ran from London and Westminster Bridges every four minutes. The river had become ‘the leading highway of personal communication between the City and the West-end’, with thirty-two trips an hour, 320 a day, carrying more than 13,000 passengers daily: this ‘

silent highway

is now as busy as the Strand itself ’. The London and Westminster Steam Boat Company reduced its 4d price to 2d for a return ticket between London Bridge and St Paul’s, and soon

penny steamers were the norm. Competition was guided solely by price, for the boats were neither luxurious nor even pleasant. There was barely any seating and no shelter on board; in the rain passengers huddled in the lee of the wheelhouse, holding up ‘mats, boards, great coats, and umbrellas’ for protection. The boats were, in addition, ‘diminutive ungainly shelterless boats...rickety, crank little conveyances’ and ‘filthy to a degree’.

At the same time, the number of companies proliferated. Operating above-bridge, in addition to the London and Westminster Steamboat Company, were the Iron Boat (which named its steamers for City companies: the

Fishmonger

,

Haberdasher

,

Spectacle-maker

), the Citizen (which used letters:

Citizen A

,

Citizen B

), and the Penny Companies. Below-bridge operators included the Diamond Funnel (the largest company, with twenty steamers, its biggest called the

Sea Swallow

,

Gannet

and

Petrel

; the medium-sized the

Elfin

and

Metis

; and the smallest, which were still larger than any above-bridge boats, the

Nymph

,

Fairy

,

Sylph

and

Sybil

), the Waterman (named for birds: the

Penguin

,

Falcon

,

Swift

,

Teal

) and the General Steam Navigation Company (its

Eagle

was known as ‘the husbands’ boat’, since it ran to the seaside resorts of Margate and Ramsgate on Fridays).

In 1846, two halfpenny steamers, the

Ant

and the

Bee

, began to run from Adelphi Pier (between present-day Charing Cross and Waterloo Bridge) to Dyers’ Hall Wharf, west of the Swan Stairs: with no intermediary stops, and double-ended boats which had no need to turn around for the return trip, the journey time as well as the price was halved. They were, rejoiced one user, ‘cheaper than shoe-leather’. But cheapness and speed had a fatal price. A year later, the

Cricket

, the company’s third boat, was berthed at the Adelphi Pier with about a hundred passengers on board. Without warning ‘a sudden report’ was heard, followed immediately by a huge explosion: such was its force that pieces of the

Cricket

’s boiler were found 300 yards away, and tremors were felt in houses at 450 yards’ distance. Immediately ‘skiffs, wherries and boats of all kinds’ put out to rescue the passengers, who had been hurled into the river. Six died, twelve were seriously injured and many more had minor injuries. It was later revealed that the engineer had tied down the boat’s safety valves so they couldn’t cut off the build-up of steam while he went for an illicit break. When the boiler overheated,

there was nothing to prevent the devastating explosion. (The engineer was convicted of manslaughter.)

This was a shocking accident, but in the period between 1835 and 1838, when steamers were at their peak, twelve were involved in serious collisions in which forty-three people drowned: nearly one fatality a month. In

Our Mutual Friend

, the owner of a riverside pub hears shouting and is told, ‘It’s summut run down in the fog, ma’am...There’s ever so many people in the river...It’s a steamer,’ to which a world-weary voice replies, ‘It always IS a steamer.’ It was not just on the water itself that danger lay. The piers were built by the steamer companies, or by the owners of the private wharves, at a time when there were no building or safety regulations, nor requirements for crowd control. One pier, at Blackfriars, gave way in 1844 when a large number of people crushed onto it in order to watch a boat race. Thirty fell into the river, of whom four may have died.