Read The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London Online

Authors: Judith Flanders

Tags: #History, #General, #Social History

The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London (20 page)

Many other sellers had no fixed pitches, but walked around selling from trays or baskets: ‘One has seedcake [for birds], another...combs, others old caps, or pig’s feet.’ Dodging among them, essential to keep the goods moving in and equally essential to purchasers to get the goods back out, were the market porters, identifiable by their porters’ knots: a piece of

fabric strapped across the forehead and hanging down over the nape of the neck, ending in a knot that secured the edge of their baskets or crates as they carried them on their backs, to distribute the weight. Some modified the fantail hats worn by workers in particularly dirty occupations, padding the fantails to provide a two-for-the-price-of-one porters’ knot and dust protection.

Covent Garden was known for its luxury imports. Other markets had their own specialities. Like Covent Garden, Billingsgate fish market on the riverside, between London Bridge and the Tower, had first been established in the seventeenth century, although fish had been sold less formally on the site even earlier. Yet, unlike Covent Garden, at mid-century Billingsgate was still nothing but a ‘collection of sheds and stalls – like a dilapidated railway station’, and even the sheds were a fairly recent addition. Despite being the world’s largest fish market, Billingsgate had been held in the open street for the previous two centuries, moving indoors only in 1849.

In the early part of the century, the market sold the local catch: in 1810, 400 boats fished the river between Deptford and London Bridge, providing Thames roach, plaice, smelts, flounder, salmon, eel, dace and dab. But by 1828, the run-off from the new gasworks near by, combined with ever more factory effluent, had destroyed the fisheries, and instead fishing boats from downriver or from coastal waters were pulled up the Thames by tugboats, with particularly delicate fish, such as turbot, brought in alive in tanks on deck. Rowboats then ferried the fish from the boats to the market. By 1850, Dutch fishing boats supplied the market with eels, while other vessels continued to bring catches from the North Sea, but the system had otherwise been modernized. The fishing boats stayed in their home waters, discharging their catch on to the faster clippers, which brought them upriver. Fish that went off quickly, like mackerel, were dropped off at the railway stations, to be put on the mail trains; having arrived by 6 a.m., they could be processed through the market to reach the fishmongers’ shops within sixteen hours of being caught.

By 4 a.m. daily the Billingsgate workers had assembled. Here the porters wore jerseys, old-fashioned breeches, porters’ fantails and thigh-high boots as they prepared for the auctions. The auctioneers themselves wore frock

coats and waistcoats, street clothes, to indicate they were middle class – Dickens called them ‘almost fashionable’ – but, as a nod to practicality, over their coats they tied heavy aprons. For much of the century these were made of flannel or coarse wool, usually serge – in

Our Mutual Friend

, set in the 1850s, the fishmonger’s men ‘cleanse their fingers on their woollen aprons’. It was only later that canvas replaced wool, while many at Billingsgate switched to oilskin.

Many of the auctioneers met at the start of the day at Billingsgate’s most famous tavern, the Darkhouse, to compare notes on quality and discuss prices over coffee or ‘the favourite morning beverage...gin mingled with milk’. At five the bell rang to announce the opening of the market, when buyers immediately headed towards their favourite stalls. Now everything was a blur of action: ‘Baskets full of turbot...skim through the air...Stand on one side! a shoal of fresh herrings will swallow you up else.’ Crowds gathered by each auctioneer as the porter set out plaice, sole, haddock, skate, cod, ling and ‘maids’ (ray) in doubles – oblong baskets ‘tapering at the bottom, and containing from three to four dozen of fish’ each – while sprats were sold by the tindal – a thousand bushes – or in offals, which held ‘mostly small and broken’ fish, to be sold off cheaply. No examination was permitted, the porter hefting each double on to his shoulder as all over the market bidding began by Dutch auction, with the auctioneer setting a high opening price, then dropping down by increments until someone made an offer. Each type of fish was sold first to the ‘high’ salesmen, who bought in bulk and then sold on to middlemen, known as bummarees, at whose stands the doubles and tindals were broken up and the contents sold off in smaller quantities to individual shopkeepers or to costermongers.

The other great market, Smithfield, was, for the first half of the century, a running sore in the City. Dickens could hardly bear it, but neither could he bear to leave it alone. This market appears again and again in his journalism, and in his novels. On market mornings, he wrote, ‘The ground was covered, nearly ankle-deep, with filth and mire...the whistling of drovers, the barking dogs, the bellowing and plunging of the oxen, the bleating of sheep, the grunting and squeaking of pigs, the cries of hawkers, the shouts, oaths, and quarrelling on all sides; the ringing of bells and

roar of voices...the crowding, pushing, driving, beating, whooping and yelling; the hideous and discordant din that resounded from every corner of the market...rendered it a stunning and bewildering scene, which quite confounded the senses.’

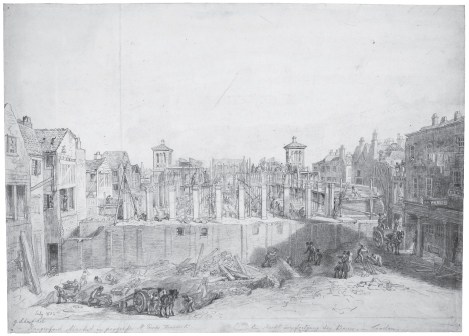

Smithfield cattle market had been held in the heart of the City since 1638. For five or six centuries even before that, a horse and livestock market had convened on the same spot, half a mile north-east of St Paul’s and a few hundred yards from the old redoubt of the City, the Barbican. By mid-century over 2,500 cattle and nearly 15,500 sheep traversed the traffic-choked streets twice weekly, before their purchasers drove them back out once more; on Friday, horses were sold; and three times a week there was a hay market. The streets leading to all the City markets were narrow and difficult to navigate: Newgate market near by had only two access roads, one just ten feet wide, one slightly less. Add the animals to the traffic and the streets became chaotic. One American resident in London said he avoided the spot on market days, because he loathed the ‘fiendish brutality of their drivers’, with calves ‘piled into a cart...and transported twenty or thirty miles, – their heads being suffered to hang out of the cart at each end, and to beat against the frame at every jolt of the vehicle’.

Smithfield itself was merely a city square measuring three acres. (In 1824, Thomas Carlyle, seeing it for the first time, was so overwhelmed by the heaving mass of animals, stench and noise that he estimated the ground it covered was ten times its actual size.) Owing to the large number of animals to be compressed into this small space, extreme cruelty was routine. ‘To get the bullocks into their allotted stands, an incessant punishing and torturing of the miserable animals [occurs] – a sticking of prongs into the tender part of their feet, and a twisting of their tails to make the whole spine teem with pain.’ All around were animals bellowing in agony as drovers ‘raved, shouted, screamed, swore, whooped, whistled, danced like savages; and, brandishing their cudgels, laid about them most remorselessly...in a deep red glare of burning torches...and to the smell of singeing and burning’. Cattle were tied to the rails ‘so tightly, the swelled tongue protruded’, before being hocked: ‘tremendous blows were inflicted on its hind legs till it was completely hobbled’. For lack of space many more were pressed

into ring-droves, circles where they stood nose to nose, wedged against the next ring-drove, driven into this unnatural formation, and kept there, by sharp goads. The goads were used so freely, were so savagely stuck into the animals, that good tanners rejected hides from Smithfield cattle, referring to them contemptuously as ‘Smithfield Cullanders’, that is, colanders, or sieves.

By the time Dickens wrote this, it was news to no one: there had been parliamentary inquiries about the horrors of Smithfield in 1828, in 1849 and in 1850, but nothing could move the obdurate Corporation of the City of London. Smithfield made a lot of money for the City, on average £10,000 per annum in fees from the sellers. As the obvious solution to the problem was to move the market to a less crowded part of London, which meant outside the City, they stalled as long as possible.

The population at large, however, could not close its eyes to the problem simply by avoiding Smithfield. The animals were driven in and out of the market through city streets clogged with ‘coaches, carts, waggons, omnibuses, gigs, chaises, phaetons, cabs, trucks, dogs, boys, whooping, roarings, and ten thousand other distractions’. By the time they were sold, they had been twenty-four hours without water or food, and it was scarcely surprising that the beasts ran amok regularly.

In

Dombey and Son

, small Florence Dombey and her nurse are walking towards the City Road on a market day when ‘a thundering alarm of “Mad Bull!”’ was heard, causing ‘a wild confusion...of people running up and down, and shouting, and wheels running over them, and boys fighting, and mad bulls coming up’. That was Dickens in fiction. A decade later, in the 1850s, he watched in reality when, in St John Street, in Clerkenwell, the same shout of ‘Mad bull! mad bull!’ was heard: ‘Women were screaming and rushing into shops, children scrambling out of the road, men hiding themselves in doorways, boys in ecstasies of rapture, drovers as mad as the bull tearing after him, sheep getting under the wheels of hackney-coaches, dogs half choking themselves with worrying the wool off their backs, pigs obstinately connecting themselves with a hearse and funeral, other oxen looking into public-houses.’ The owner pelted along behind the animal until he finally found his bull in ‘a back parlour...into which he had violently

intruded through a tripe-shop’. This sounds more like fiction than the fiction itself, but similar reports routinely appeared in the journals.

Non-cattle-market days were no quieter. Friday afternoons were costermongers’ day at Smithfield, when the costers purchased the tools of their trade: 200 donkeys were sold on a concourse about eighty feet long while a smaller area held ponies. Barrows and carts were offered for sale, as were spare parts – wheels, springs, axles, seats, trays, or just old iron for running repairs. Harnesses, bridles and saddles were hung from posts or spread on sacking on the ground, as were smaller necessities, such as whips, lamps, curry-combs and feed-bags. Even at this much smaller market, Smithfield was ill suited for the number of people who attended. The concourse itself was paved, but the surrounding selling areas became so churned up and mixed with animal dung that the policemen on duty habitually wore thigh-high fishermen’s or sewermen’s boots; the costers accepted that their trousers would be ‘black and sodden with wet dirt’.

Finally, in 1852, the Smithfield Removal Bill was passed in Parliament, and the live meat market was closed in 1855, moving to Copenhagen Fields in Islington. In 1868, the old Smithfield ground, now called West Smithfield, was re-established, this time as a dead-meat market – that is, for butchered meat, not live animals – complete with an underground station to bring in the goods for sale. (The hay market survived at Smithfield because officials had forgotten to allow space for it in the new market in Islington; it continued until 1914, when the rise of the car made it redundant.) No longer would the cry of ‘Mad bull!’ run through the City. The new market was iron-roofed, gaslit, with wooden stalls: the epitome of modern trade elegance, complete with restaurants and drinking establishments, and rooms for dining, meeting, or reading the newspaper. Other markets had to wait longer for renovation. Leadenhall had been the largest market in Europe, selling dead meat, skin and leather; herbs and ‘green’-market goods; pigs, and poultry, in three separate yards, from 1400. Gradually poultry became its main item (in

Dombey and Son

, Captain Cuttle hires ‘the daughter of an elderly lady who usually sat under a blue umbrella in Leadenhall Market, selling poultry’), and in 1871 an Act was passed to prevent the old market from continuing to sell hides or meat.

These specialist markets serving the whole of London were the exception. Many neighbourhoods supported a small market of one sort or another, and most had several. In the streets around Oxford Street, for example, there were Carnaby market, ‘now but a small provision market’; Oxford market, near Portland Street, which sold vegetables and meat; Portman market, for hay, straw, butter, poultry, meat and ‘other provisions’; St George’s market, at the western end of Oxford Street, primarily for meat, but with many nearby vegetable stalls; Mortimer market, ‘a very obscure market’; and Shepherd’s market, on the south side of Curzon Street, for provisions generally, ‘a convenience for this genteel neighbourhood, and...not a nuisance’. (It is notable that only in this very exclusive district does the compiler of this list consider that a market might be a ‘nuisance’.)

Around the Strand and Covent Garden was Hungerford market (underneath what is now Charing Cross station), which sold fish, fruit, vegetables and dead meat. It also had a number of poulterers’ shops, with live cockerels

and hens, their black beady eyes peeping through the wicker baskets. Beside these basics, according to one author mid-century, the market was also known for its penny ices, advertised as ‘the best in England’. Hungerford had been covered over since the seventeenth century, but in 1830 it was expanded and rebuilt on three levels, with a fish market below and fruit and vegetables above. Dickens was spotted here one day in 1834, behind a coal-heaver carrying a child who peeked shyly over his father’s shoulder at the young journalist. Dickens promptly bought a bag of cherries and, walking along, posted them one by one into the child’s mouth without his father being aware, ‘quite as much pleased as the child’.