The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London (47 page)

Read The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London Online

Authors: Judith Flanders

Tags: #History, #General, #Social History

Fluctuating attitudes to royalty could partly be gauged by the crowds in the streets. Victoria’s reign began with scant public interest. In 1837, after William IV’s death, the new queen was driven from Kensington Palace to St James’s, an event that prompted so feeble a public reaction that one observer commented, ‘I was surprised to hear so little shouting, and to see so few hats off as she went by.’ When she appeared at the palace window for the formal proclamation, ‘the people…did not…hurrah’ until they were urged on by a courtier. Six months later, on her way to the House of Commons, ‘not a hat [was] raised’ as the new queen passed, and at Ascot she was ‘tolerably well received; some shouting, not a great deal, and a few hats taken off’. The political diarist Charles Greville was clearly not impressed.

108

Her coronation got off to a bad start. The original date had been set for 20 June 1838, which was the first anniversary of the death of William IV. The opposition claimed that a cheeseparing government had done this deliberately, as a way of saving money by claiming it was a day of mourning. The date was therefore moved to 28 June, provoking the trade element to complain again: first, that they had not been given adequate time to produce souvenirs; then, that by the time the date had changed, they had already produced souvenirs, all of which carried the wrong date. Disraeli,

a very new MP, was scarcely more enchanted even a week before the event. As MPs were obliged to wear formal court dress, he told his sister that he planned to save his money and stay away from the ceremony, sooner than attend ‘dressed like a flunky’. However, a few days later he wrote wistfully, ‘London is very gay,’ with the processional route ‘now nearly covered with galleries and raised seats’, which he thought would look superb once they were decorated with ‘carpets and colored hangings’. Diplomatic London, too, was seething with foreign dignitaries, ‘visible every night with their brilliant uniforms and sparkling stars’. Unsurprisingly, Disraeli attended the ceremony ‘after all’, using it as an opportunity to store up droll episodes: Lord Melbourne ‘looked very awkward and uncouth, with his coronet cocked over his nose’, and clutching the sword of state ‘like a butcher’, while ‘ribboned military officers and robed aldermen…were seen…wrestling like schoolboys…behind the Throne’. One elderly peer, Lord Rolle, having climbed the stairs to the throne to make his bow, caught his foot in his coronation robes and tumbled down them again. Wicked Disraeli solemnly told visitors that Lord Rolle’s roll ‘was a tenure by which he held his Barony’.

While the crowd loved a parade, it was not yet committed to loving those who paraded. Two years later, Victoria’s fiancé was referred to in street songs as a ‘German sausage’ (lewd subtext intended). And while ‘a countless multitude’ stood in the driving rain to watch the royal bride pass by on her way to the wedding, they did so ‘without any cheering’. Later, popular attitudes fluctuated with events. When a royal child was born (and there were nine of them), salutes were fired in the parks, while a greater or lesser number of private individuals and commercial premises marked the occasion with decorations. In 1842, few buildings bothered to display illuminations for the birth of the Prince of Wales (for more on illuminations, see pp. 363–9), and in 1848, after the queen gave birth to yet another child, when ‘God Save the Queen’ was played at the theatres, a number of ‘ill-mannered’ people refused to take off their hats. The ‘sorry usage’ shown by more fervent royalists was recorded by one journal as indicating ‘loyal enthusiasm’. However, in the same magazine, when a miser named Neild died, leaving more than £250,000 to the queen, it

was noted laconically that the will was most likely to be disputed ‘on the ground of insanity’.

109

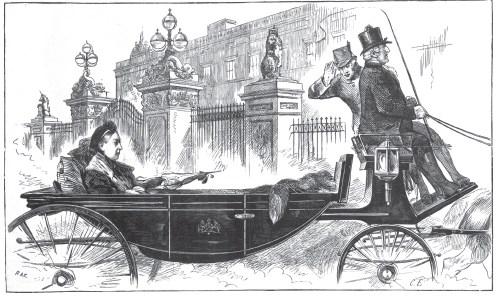

It was the seven attempts to assassinate the queen that drew the strongest public displays of admiration, and then affection, until in time the monarch’s advanced age and longevity on the throne eventually prompted veneration. The first such attempt was in 1840; in 1842 two more followed within days of each other. After the first, which occurred while she was out driving, the queen quickly visited her mother, to reassure her, then returned to the park, where ‘she was received with the utmost enthusiasm by the immense crowd’; all the men on horseback ‘formed themselves into an escort and attended her back to the Palace, cheer[ing] vehemently’. This may be the first time Greville recorded seeing active cheering for Victoria, adding that the incident had ‘elicited whatever there was of dormant loyalty’. After the first of the two 1842 attempts, the following morning ‘numbers of respectable persons’ stood outside Buckingham Palace for hours until the queen and her party drove out for her regular airing in the park. The queen, despite the attack, still used her open barouche, which elicited ‘one long, loud, and continued shout of hurrahs, accompanied by the waving of handkerchiefs and hats’. The road from the palace to Hyde Park Corner was lined with people, and the park, too, was dense with spectators: when the queen arrived, ‘not a head was covered’, which was a big change in a few years. By the time of the fifth assassination attempt, in 1850, theatregoers had become accustomed to welcoming the queen after such an episode. The young Sophia Beale was at Covent Garden that evening to see Meyerbeer’s

The Prophet

:

We were in a small box up at the top of the theatre opposite the royal box and all of a sudden every one stood up and cheered and made a great noise. Then we saw the Queen and Prince Albert come into the box, and they came to the front and bowed and looked very pleased. And then Madame Grisi rushed on the stage in evening dress from her box, she was not acting, and all the singers sang

God save the Queen

… Papa went out and asked the box keeper what had happened, and he said a man

had thrown a stick at the Queen when she was driving in the Park, but it did not hurt her.

110

So after they had sung

God save the Queen

, the opera went on.

Such imperturbability impressed everyone. Four years later, Dickens watched Louis Philippe, the king of France, driving out in Paris. He too had survived an assassination attempt, but, wrote Dickens contemptuously, ‘His [carriage] was surrounded by horseguards. It went at a great pace, and he sat very far back in a corner of it, I promise you. It was strange to an Englishman to see the Prefect of Police riding on horseback some hundreds of yards in advance…turning his head incessantly from side to side…scrutinizing everybody and everything, as if he suspected all the twigs in all the trees.’

But the public’s affection waned as rapidly as it had grown, again precipitated by the queen’s behaviour. After the death of Prince Albert in 1861, Victoria went into seclusion, observing a level of of widowly mourning considered extreme even by nineteenth-century standards. Although a year or even two of private grief would have been respected, the queen kept obstinately to Windsor and her two private homes, Osborne and Balmoral, year after year, refusing to live in London or to perform her ceremonial functions. Soon the public made it quite clear that they saw this as a dereliction of duty. In 1864, a notice was posted on the railings of Buckingham Palace: ‘These commanding premises to be let or sold, in consequence of the late occupant’s declining business.’ Four years later, with no change in sight, less witty placards began to appear in the streets more generally:

VICTORIA!

Modest lamentation is the right of the dead;

Excessive grief is the enemy of the living.

— Shakespeare

This quote was followed by a number of advertisements, which suggests a commercial source. Even later in the decade, when the queen did perform certain public duties, such as attending the opening of the great engineering project that was Holborn Viaduct in 1869, many thought she did so grudgingly. She arrived by train from Windsor and travelled in state to Blackfriars Bridge, which she formally opened, before moving in procession to the eastern end of Holborn Viaduct. Having opened this too, as the

Illustrated London News

noted sharply, she then ‘quit the City’, scuttling back to Paddington to catch a train to Windsor a few hours after arriving in the capital.

Perhaps it was this sense of London being abandoned by royalty that provoked the outpouring that greeted Princess Alexandra on her arrival in the city in 1863. All the way from the Bricklayers’ Arms station in Camberwell, where the Danish party was scheduled to arrive, up to Paddington, where it was to re-embark for Windsor, ‘every house has its balcony of red baize seats; wedding favours fill the shops, and flags of all sizes’.

111

A week beforehand, banners were already flying. London Bridge was festooned in scarlet hangings, with a triumphal arch ‘as big as Temple Bar’, and, in the recesses of the bridge, ‘massive draped pedestals, surmounted by Mediaeval Knightly figures: rows of tall Venetian standards with gilt Danish elephants atop’, while between them were placed ‘great tripods of seeming bronze, from which incense is to arise’. None of this was to celebrate the wedding itself, which was to be a gloomy private occasion in Windsor, with the queen still in deep mourning. Rather, these decorations were merely to greet the soon-to-be Princess of Wales as she drove across the city from one railway station to another.

Despite the brevity of this visit, the day was a ‘universal holiday’, with crowds everywhere. Fleet Street and all the way along to Blackfriars Bridge ‘was given up to Pedestrians, who filled the whole of it as far as one could see’. Steamers were unable to dock at London Bridge, so congested were the steps. ‘Every avenue to [the bridge] was barricaded with vehicles full of sightseers…every visible window and housetop on every side was filled with gay people, wearing…wedding favours or Danish colours: a vast and compact multitude filled the streets: banners and illumination devices appeared everywhere: the triumphal arch on the Bridge, now finished, was glorious with white & gold and bright colours.’

The carriages took an hour to cover the half-mile between the Bricklayers’ Arms and London Bridge, slowed to a crawl by the dense jam of spectators.

112

The first coaches were cheered heartily by people pleased to be pleased. Then, ‘when the last open carriage came in sight, the populace, who had been rapidly warming to tinder point, caught fire all at once. “Hats off!” shouted the men: “Here she is!” cried the women: and all…surging

round the carriage, waving hats and kerchiefs, leaping up here and there and again to catch a sight of her…her carriage was imbedded in eager human faces, & not the scarlet outriders with all their appeals…could make way one inch.’ On the day of the wedding itself, trains into London were ‘decked with flowers and evergreens, and nearly all the passengers wore wedding favours…every station on the line was dressed with flags and flowers, and…there were sounds of guns and blazing of fireworks’. The crowds, estimated at 2.5 million people, were happy to enjoy the decorated streets even without the principal players.

However, it wasn’t necessary for a visitor to be royal to receive an eager and passionate popular reception. The year after Alexandra’s marriage, as much uproar was generated by the hero of Italian unification, Giuseppe Garibaldi, who was given a welcome every bit as tumultuous, with streets every bit as jam-packed, as were the houses overlooking the route. Garibaldi, too, arrived at the Bricklayers’ Arms, where the band of the United Italians in London, all in red shirts, played on the platform, under banners reading: ‘The Pure Patriot’, ‘The Hero of Italy’ and ‘The Man of the People’.

113

Unlike Alexandra, Garibaldi was staying in London, travelling in over Westminster Bridge and up to the now symbolic centre of Trafalgar Square. Sophia Beale, who was in the throng at the bottom of the Haymarket, watched him, ‘standing up in the carriage in his historic red shirt and grey cloak, bareheaded’ as onlookers ‘clambered on to the carriage, and would have liked to have taken the horses out to drag it’. When Garibaldi visited the Crystal Palace on the following Saturday, ‘Some thirty thousand people were present,’ with many women wearing dresses in red, white and green, the Italian colours; his visit to Anthony Panizzi, the Italian political exile turned British Museum librarian, drew huge numbers of spectators all along Great Russell Street. (More enduringly, it was this trip that decided one manufacturer to name its new raisin biscuit the Garibaldi.)

Yet all these celebrated folk were minor diversions in a street life that was constantly filled with theatre. As well as the many unscheduled events, there were a number of days every year that the people celebrated entirely or primarily on the street.