The Virgin Cure (19 page)

The scent of roasted peanuts and steamed oysters wafting from nearby vendors’ carts nagged at my belly, making it impossible for me to refuse Mae’s invitation.

By the time we got to Graff’s, the courtyard was busy with people milling about, mostly men who’d come to drink beer and play checkers. A few women were there as well, tending to small children or babies they’d brought out for a stroll.

I recognized the gentleman standing in line in front of us as a regular. From the place where I sat at Mr. Mueller’s to do my nibbling each day, I’d watched the lanky, well-dressed gent come and go from Graff’s, his countenance always fairer after his belly was full. He’d sometimes dropped a penny at my feet on his way past the bakery door, but he’d never bothered to look me in the eye.

“The usual, sir?” the oyster opener asked him when it was his turn at the stand.

Pulling a shiny two-pronged fork from his pocket the gentleman flashed it at the stabber and said, “Yes, indeed.”

“A dozen Blue Points, clear, coming right up,” the opener declared.

The gentleman watched as the stabber began slinging oyster after oyster with his knife. “You’re the chief surgeon of stabbers, my friend,” he teased.

Deftly plopping the half-shells in a basket, the stabber boasted cheerfully, “Straight from the bi-valvery institute …”

The round-faced oyster man’s smile grew even broader when he saw Mae approach. I wondered exactly what she’d meant when she said she was friendly with him.

“Two bowls of the best oyster stew outside of Dorlan’s,” Mae announced to the opener as we stepped up to his stand.

“Best oyster stew

anywhere,”

the stabber replied. Ladling milky hot stew from a pot, he gently scolded Mae. “A pretty girl like you has no business being down by the river. When you want a belly full of oysters don’t you dare go to Dorlan’s. You come see me.”

Mae winked at him and paid for the two steaming bowls of stew. Then she gave him another handful of pennies for a plate of beans and some crackers.

“It’s all Shrewsburys in there, I’ll have you know,” he said, his cheeks pinking up with the touch of Mae’s gloved hand.

“Little oysters are the sweetest and in every way better,” she replied.

The oyster man took her money, returning her wink, and then gave me a terrible frown. For a few, all-too-easy moments, I’d forgotten my place on the Bowery. In an instant, the oyster man’s disapproving gaze brought me back down to where he thought I belonged.

“She’s all right,” Mae told him, giving him a pout. “She’s with me.”

Buckling to Mae’s appeal, he motioned for the two of us to go into the garden. “Go on, take a seat,” he said, waving us through. “I won’t charge you nothing for it.”

It was a lovely day, with a gentle breeze and a sun so warm you’d almost think summer was trying to come back for an encore. An

oompah

band was playing away under a half-tent in the corner of the garden, the musicians’ cheeks puffed fat with every note. I walked beside Mae, forgetting the state of my dress and the oyster man’s stare. One look from her had made it easy to pretend life was perfect.

As we settled ourselves at the end of a long table she asked, “How old are you, Moth?”

“Twelve,” I said, reaching for my bowl of stew.

“I would’ve guessed fourteen, maybe fifteen,” she said. “You seem much older than twelve.”

Slurping a hunk of oyster down my throat, I croaked, “Thanks.”

“Do you sleep on that roof every night?”

“Most nights.”

“You can’t go back there now, though,” she said. “Not after what happened.”

“No, I guess not.”

As it was, I rarely slept the night through on the roof. Tucked inside my barrel, I’d stay awake listening for voices and footsteps that came too near. I feared someone might give the barrel a shove and roll me off the edge of the building, or at the very least try to oust me from my spot. When I did manage to fall asleep, visions of Mrs. Wentworth haunted my dreams. She’d cackle and scream as she tried to strangle me with the ribbon that secured her fan around my neck. Gasping, I’d wake, crying out for Mama.

“I know someone who can help you make a new start,” Mae said, pushing her bowl aside. “She’ll put you in new clothes, give you a place to stay—”

The cut of her dress, the quality of her boots, the winning smile she’d given the oyster opener all pointed in one direction.

“Are you a whore?” I whispered, interrupting her before she could finish.

My question, blunt and awkward as it was, didn’t seem to bother her in the least. Tugging at the wrists of her gloves and pulling them taut, she looked me in the eyes and replied, “Almost.”

M

ae confided that after she’d gotten out of the situation with the false marriage broker, she’d called on the only person she knew in the city, a young woman named Miss Rose Duval. Also from Patterson, New Jersey, Miss Duval was a distant cousin of Mae’s who had once shown promise as a stage actress, but through a chain of unforeseen events wound up a whore instead.

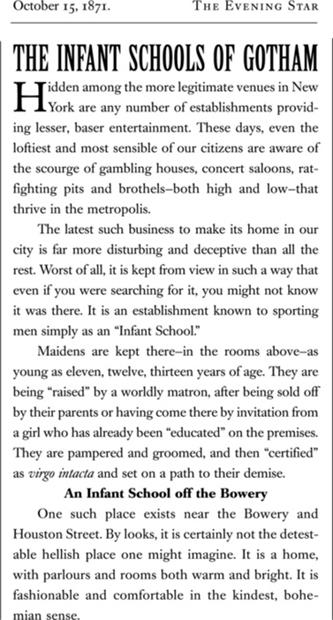

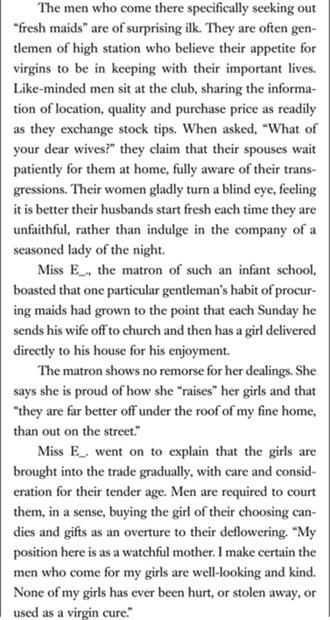

In 1871, under common law, the age of consent was ten years of age. (In Delaware it was seven.)

The young girls of New York understood (for better or for worse) the value of declaring themselves to be of a palatable age to gentlemen. Twelve sounded far too young to the ears of any man with a conscience or heart. Sixteen, even when uttered by honest lips, inevitably brought the girl’s purity into question.

Of the years left between, fifteen was declared to be the ideal number.

“I didn’t know any of it until I saw her again,” Mae said. “Even her mother had no inkling she’d become a belle of the boudoir rather than a star of the stage.”

Mae had begged Rose to help her, explaining that she had her reasons for not returning home, the greatest of which was the terrible beating she’d get from her father if she dared to show her face again at his door. Seeing Mae’s distress, Rose promised to find a way to assist her.

“He’s not my real father,” Mae said, after noticing the concerned look on my face. “He’s just the man my mother married after Papa didn’t come back from the war. He loves her and hates me. It’s as simple as that.”

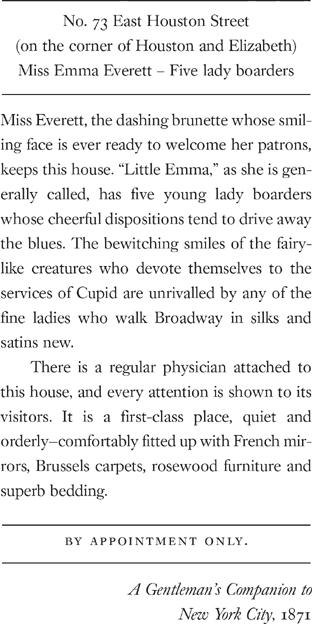

I knew when it came to love or bruises, nothing was ever simple. Still, I chose not to press Mae to talk further about her family. I didn’t want her asking after mine, and her past wasn’t nearly as important to me as the fact that she was now a girl-in-training at a first-class brothel on Houston Street.

“There’s whores and then there’s near-whores,” Mae said, as we walked together up the Bowery. “And only the best madams in the finest brothels know how to make something out of the difference between the two.”

Motioning to the stoop of a clean, modest-looking house just ahead of us, she said, “You wait here. I’ll go in and get Miss Everett to come meet you.”

“All right,” I replied, taking a spot halfway up the steps.

“Oh, and remember,” Mae added, turning back. “You’re fifteen years of age—fourteen if she doesn’t believe you.” Then she opened the door and disappeared inside the house.