The Virgin Cure (6 page)

Staring at the shadow where the slant of the roof came down to meet the floor, I put my nose to the pillowcase, breathing through the cloth like a baby nuzzling the sleeve of her mother’s dress. It smelled of rosewater, Dr. Godfrey’s cordial and money-drawing oil. Mama had taken to anointing herself with the latter, believing that the musty-smelling concoction would bring customers to our door.

Before taking me away, Mrs. Wentworth had placed a small, velvet bag in the middle of Mama’s fortunetelling table. Tied up with a drawstring, its contents had sweetly jangled as it came to rest. It was Mama’s payment for letting me go, a sum of good faith.

I wondered what the weight of the bag would feel like if I held it in my hand, and if any coins had spilled on the floor when Mama untied the string. Had a penny rolled into a crack between the boards, causing her to curse? Had she put the coins to her face to feel their coolness on her cheek?

By the age of five, I was stealing buckets of coal and bundles of sticks for Mama’s tiny, rusted stove. I’d pumped bucket after bucket of water in the middle of our muddy, stinking courtyard, scrubbed other people’s clothes and hung them up to dry—all the while hoping I’d wake up one morning to find my father had come back to us and Mama had turned into the lady on the side of the Pure and True Laundry Flakes box. She was a round-faced mother dressed in calico, with a clean white apron around her waist. Her eyes smiled as she puckered her lips, forever kissing the top of her little girl’s head. Along the hem of her skirt a slogan was written:

Mother, if you love her, you’ll keep her clean

.

Mama must’ve had an amount in her head she wanted for me, a sum she considered right and fair—more than she’d got for my boots or her tortoiseshell combs or the trinket she wore around her neck, enough to buy the largest bottle of

Dr. Godfrey’s

Mr. Piers had locked away in the old sea chest he strapped to the back of his cart.

How much did you get for me, Mama?

I whispered in the dark.

I

woke to see Mrs. Wentworth’s housekeeper, Caroline, pouring water from a pitcher into a deep, waiting bowl. She glanced at me when she heard me stir, but didn’t say a word.

Setting the pitcher aside, she stared at her reflection in a mirror that was hanging in front of her on the wall. The silver backing was cloudy and pitted, so that one half of her face—her neck, her mouth, her nose—was a streaky blur. One eye, steely and clear, blinked back at her, one cheek blushed ruddy in the morning sun that shone through the room’s narrow skylight. The calico kerchief on her head wasn’t nearly as fetching as the silk scarf Mama always wore, but the field of tiny cornflowers suited her, their cheerful blue petals making a welcome halo of softness around her stern countenance.

Thin-lipped and flat-chested, she bore all the signs of a woman whose labours had added to her years. Her hands were wrinkled, her nails ragged, her neck veined with impatience.

I watched as she scrubbed her face, as she slipped a drippy sponge under her skirts and up between her legs. After she finished, she gave a short nod in my direction indicating my turn at the basin.

“Thank you,” I said, smiling and hoping for a smile in return. I wanted to get on her good side, since I was all but certain she’d be the one ordering me to scrub floors and polish silver.

As I went to the basin I introduced myself, but she ignored me, pretending to be busy with pinning a small tear in the hem of her skirt. When I asked how many other girls were in the house, she merely rolled her eyes and grunted.

“Lady’s got herself another green one,” she grumbled as she walked past me to the other side of the room.

Just by being here, it seemed, I’d already gone wrong.

Opening the door of a large wardrobe, Caroline brought out a maid’s dress. Practical looking but pretty, it had a row of shiny buttons up the front, and matching lace collar and cuffs. She inspected the garment front and back and then laid it across my mattress. Going to the wardrobe a second time, she fetched a pair of boots from the bottom drawer and then placed them on the floor next to my bed.

“Thank you,” I said again, making my voice as sweet as I could, hoping she’d forget herself and say something in reply. She did not.

Pulling the dress over my head, I caught the faint smell of sweat from the girl who’d worn it before me.

Who was she? Where was she now?

Even second-hand, the dress was nicer than anything I’d ever owned. I couldn’t help but admire the cut of it, how the pleats came racing down the front of the waist, how the buttons sat in a straight, neat row after I’d fastened them. Caroline gave me a sideways look, clearly trying to discern if the dress would suit. I turned in place, smoothing the brushed cotton cloth against my belly. She needn’t have worried. The dress fit fine.

The boots, however, were another matter. Although they were polished and whole, the leather was stiff and unforgiving. As I slid my feet inside them, my toes poked through the holes in the ends of my stockings, rubbing against the boots, threatening to blister even before I stood up. Laces loose, they still felt tight. I took them off and put them on again, and then did it again, each time tugging at the ends of my stockings until the holes were tucked under my feet. Still, my toes found their way out to rub against the leather.

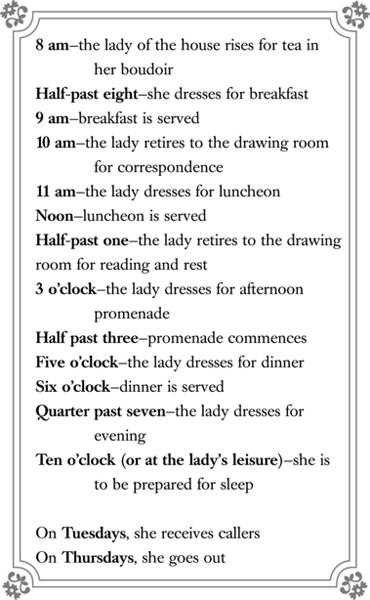

“Lady’s got to have her tea by eight,” Caroline said, heading for the door.

I gave up on the stockings and hurried to tie my boots. I followed her down the same flight of narrow stairs I’d come up with Nestor the night before, this time descending past the doorway to the main floor of the house and into the kitchen below.

Nestor was there, tending a fire in one of the three large stoves that lined one wall. “Good morning, Caroline,” he said, greeting the housekeeper with a cheerful voice.

She responded with a distracted, “We’ll see.”

“Good morning, Miss Fenwick,” he said, now turning to me, “I trust you slept well?”

“Yes, fine, sir,” I replied, relieved to find he hadn’t changed his ways towards me because of Caroline’s attitude.

I looked around, thinking I might find at least one other maid preparing for the day, but there were only the three of us, Nestor, Caroline and me.

I watched as Caroline took a loaf of bread from a basket and began tearing it apart. She placed three metal soup bowls in front of her and put several hunks of bread into each one. When I stepped close and offered to help, she jabbed a sharp elbow into my ribs and shoved me aside. Wincing, I decided to act as best I could on her nods and shrugs until she saw fit to direct me with her words.

Once the bowls were filled with bread, Caroline went to the cupboard and brought out a large, heavy crock. After removing the crock’s lid, she took up a ladle and plunged it through the thick layer of fat that sat across the top of the pot. “One for you, one for you, one for you,” she whispered to herself as she deftly poured ladlefuls of broth into the bowls. The ragged pieces of bread melted with the weight of the liquid, turning moist and brown. Caroline looked at the last bowl with a great deal of satisfaction. She hadn’t spilled a drop.

“Have some, Nestor,” she called out to the butler, presenting him with his serving before I could get to it.

Nestor took the bowl from her hands and then sat down at the wooden table in the centre of the room. Catching my eye, he gestured for me to do the same. I hesitated, and shook my head, thinking I should wait for Caroline to take hers first.

The mere sight of food had started my belly rumbling. The thought that bread could be kept in a house with no danger of it summoning a pack of rats was nothing short of a miracle to me.

How much food was there?

It seemed to be coming out of every cupboard and corner and I imagined that if I could steal into the kitchen without anyone knowing, I could take whatever I wanted. Sitting in the middle of the floor, I’d eat until crumbs and grease were dripping from my chin.

“I took the liberty of filling the kettle for the lady’s tea,” Nestor informed Caroline before lifting his bowl to his lips. “It should be plenty hot by now.”

“That’s fine,” she replied, bringing out a silver tea service and placing it on a tray at the other end of the table.

I waited for a moment when I might be of use to her. This, however, only caused more trouble. The next time she turned around we were nose to nose and I could see by her scowl that my persistence had angered her. She brushed past me in a huff, and I gave up, taking one of the remaining bowls of bread and broth and sitting down across from Nestor. His eyes crinkled into a smile as I settled in my chair.

Free from my hovering, Caroline glided between table and cupboards, artfully arranging delicate bowls and plates, filling them with sugar and milk, grapes and pears. Now that there was distance between us, I could see she had a sense of grace about her. Like the tiny wooden woman who inhabited the cuckoo clock in the window of the jeweller’s shop on Second Avenue, her waist was constantly moving in sympathy with her skirts, turning round first this way, then that.

“Where’d the lady get to last night?” she asked Nestor as she snipped at the stems on a bunch of grapes with a small pair of scissors.

“Chrystie Street, I believe,” he answered, looking to me for confirmation.

I gave him a nod before taking a sip of broth. It tasted of beef, rich with salt and onion, so good I forgot myself. Gulping and slurping, I carried on until every bit of the bread had slithered down my throat.

“Went slumming again, did she?” Caroline asked, one eyebrow arching. “You think she would’ve learned, after the last one …”

Staring at Caroline, Nestor tipped the edge of his bowl against the table with his finger. The last of its contents spilled out from it, running in a stream, straight towards a folded, white napkin that the housekeeper hadn’t yet placed on the tray.

“Chrystie Street,” she muttered as she scrambled to rescue the napkin. “Never heard of it … sure hope it’s better than

Ludlow.”

If she’d bothered to ask me, I would’ve said with great confidence that it was. I would have told her that the people on Chrystie Street were a cut above, that everything they did was a matter of pride, and that if she’d never been there, she was all the poorer because of it.

I would’ve been lying, of course. While Ludlow and Chrystie streets both had their share of falling-down tenements, Ludlow had sewers and Chrystie Street had none. All slums are not created equal.

When Caroline turned away, Nestor nicked a pear from the bowl of fruit sitting on the tea tray. Cutting it into slices with his pocket knife, he offered me a piece. Made bold by Caroline’s disdain, I took it.

The fruit was sweet and juicy in my mouth, not like the mealy, past-ripe pears sold on street corners or at Tompkins Market. Those pears floated in buckets of syrup for weeks at a time, young girls selling them with false promises of “fresh firm fruits from the farm—just picked today …”

As Nestor’s long, sly fingers came towards me with another slice, I thought of my father. He, too, was a thief. Mama always swore that he’d stolen both her and a horse from right under my grandfather’s nose in broad daylight. “Stealing a horse from a Gypsy is no easy feat,” she’d say, closing her eyes in bliss and sadness whenever she brought the memory to mind. I’d supposed all kinds of things about my father when I was young. In my dreams, he never appeared on Chrystie Street. Instead, he was always dancing around the apothecary’s pear tree, pouring sugar from Mama’s silver bowl down between the tree’s roots. “I like my pears sweet,” he’d say just before he would disappear.

As I reached to take the last slice from Nestor, I caught sight of Caroline’s hand coming towards me, a wooden spoon clenched in her fist. Before I could move, she smacked the spoon on the table, so hard it made me jump. “Damn fly,” she said, staring right at me.

Nestor let out a nervous chuckle and said, “Poor thing never had a chance.”

Sour-faced, Caroline had opened her mouth to scold him, when she was interrupted by three sharp rings coming from a row of bells strung along the wall by the stairs. Each of the bells had been labelled for a room in the house—

parlour, study, dining hall, foyer, master’s chamber, bath, library, conservatory …

When the ringing came again, I saw that it was from the bell marked

lady’s chamber

.