The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 (49 page)

Read The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 Online

Authors: Margaret MacMillan

Tags: #Political Science, #International Relations, #General, #History, #Military, #World War I, #Europe, #Western

She was a great publicist and superb lobbyist. Among much else she founded the Austrian Peace Society in 1891 and edited its journal for many years; she was active in the Anglo-German Friendship Committee; she bombarded the powerful of the world with letters and petitions; she wrote articles, books and novels to educate the public about the dangers of militarism, the human costs of war and the means by which it could be avoided; and she spoke widely at conferences, peace congresses, and on lecture tours. In 1904 President Teddy Roosevelt gave her a reception at the White House. She persuaded the rich, among them the prince of Monaco and the American industrialist Andrew Carnegie, to support her work. Her most important patron of all was her old friend and employer, Nobel. His fortune was based on his patenting and production of the new and more powerful explosive of

dynamite which had immediate application for mining but which was, in the longer run, to add to the increasingly greater destructiveness of modern weapons. ‘I wish’, he once said to Suttner, ‘I could produce a substance or machine of such frightful efficacy for wholesale devastation that wars should therefore become altogether impossible.’

3

When he died in 1896, he left part of his considerable fortune to endow a prize for peace. Suttner, who was yet again in financial difficulties, turned her lobbying talents to the prize and in 1905 was awarded it.

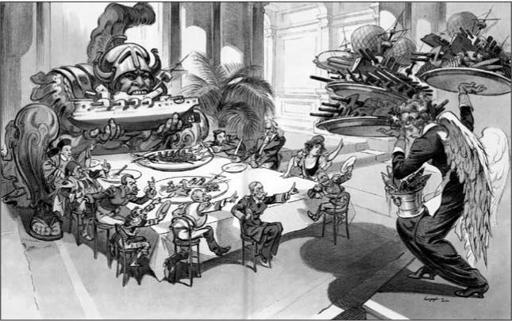

10. Before 1914 a powerful international peace movement was committed to outlawing or at least limiting war. Although one of its goals was to end the arms race, it had little success. In this cartoon, at one end of the table Mars, the God of War, is chewing on a dreadnought while figures representing the world’s powers, including France’s Marianne, an Ottoman Turk, a British admiral and Uncle Sam, angrily demand their meal of weapons. The poor waitress Peace struggles with her heavy trays, her wings bedraggled and her head bowed; ‘Every hour is lunch hour at the Dreadnought Club’.

In her views, she was very much a product of the confident nineteenth century with its trust in science, rationality and progress. Surely, she thought, Europeans could be made to see how pointless and stupid war was. Once their eyes had been opened they would, so Suttner fervently believed, join her in working to outlaw war. While she shared the Social Darwinist concepts about evolution and natural selection, she – and it was typical of many in the peace movement – interpreted them differently from the militarists and generals such as her compatriot,

Conrad. Struggle was not inevitable; evolution towards a better more peaceful society was. ‘Peace’, she wrote, ‘is a condition that the progress of civilization will bring about by necessity … It is a mathematical certainty that in the course of centuries the warlike spirit will witness a progressive decline.’ John Fiske, a leading American writer and lecturer in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, who helped to popularise the idea of the United States’ manifest destiny to expand into the world, believed that it would happen peacefully through American economic power. ‘The victory of the industrial over the military type of civilization will at last become complete.’ War belonged to an earlier stage of evolution and indeed to Suttner was an anomaly. Eminent scientists on both sides of the Atlantic joined her in denouncing war as biologically counter-productive: it killed the best, the brightest, and the most noble in society. It led to the survival of the unfittest.

4

The growing interest in peace also reflected a shift in thinking about international relations from the eighteenth century: they were no longer a zero-sum game; by the nineteenth century there was talk of an international order in which all could benefit from peace. And the history of the century appeared to demonstrate that a new and better order was emerging. Since the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 Europe had, with minor interruptions, enjoyed a long period of peace and its progress had been extraordinary. Surely the two things were linked. Moreover, there appeared to be growing agreement on and acceptance of universal standards of behaviour for nations. In time, no doubt, a body of international law and new international institutions would emerge, just as laws and institutions had grown within nations. The increasing use of arbitration to settle disputes among nations or the frequent occasions during the century when the great powers in Europe worked together to deal with, for example, crises in the decaying Ottoman Empire, all seemed to show that, step by step, the foundations were being laid for a new and more efficient way of managing the world’s affairs. War was an inefficient and too costly way of settling disputes.

Further proof that war was becoming obsolete in the civilised world was the nature of Europe itself. Its countries were now tightly intertwined economically and trade and investment cut across the alliance groupings. Britain’s trade with Germany was increasing year by year before the Great War; between 1890 and 1913 British imports from

Germany tripled while its exports to Germany doubled.

5

And France took almost as many imports from Germany as it did from Britain while Germany for its part depended on imports of French iron ore for its steel mills. (Half a century later, after two world wars, France and Germany would form the European Iron and Steel Community which became the basis of the European Union.) Britain was the world’s financial centre and much investment in and out of Europe flowed through London.

As a result the experts generally assumed before 1914 that a war between the powers would lead to a collapse of international capital markets and a cessation of trade which would harm them all and indeed make it impossible for them to carry on a war for longer than a few weeks. Governments would not be able to get credit and their people would become restive as food supplies grew short. Even in peacetime, with an increasingly expensive arms race, governments were going to run into debt, raise taxes or both, and that in turn would lead to public unrest. Up-and-coming powers, notably Japan and the United States, which did not face the same burdens and enjoyed lower taxes, would be that much more competitive. There was a serious risk, leading experts on international relations warned, that Europe would lose ground and eventually its leadership of the world.

6

In 1898, in a massive six-volume work published in St Petersburg, Ivan Bloch (also known by the French version of his name as Jean de Bloch) brought together the economic arguments against war with the dramatic developments in warfare itself to argue that war must become obsolete. Modern industrial societies could put vast armies into the field and equip them with deadly weapons which swung the advantage to the defence. Future wars, he believed, were likely to be on a huge scale, draining resources and manpower; they would turn into stalemates; and they would eventually destroy the societies engaged in them. ‘There will be no war in the future’, Bloch told William Thomas Stead, his British publisher, ‘for it has become impossible, now that it is clear that war means suicide.’

7

What is more, societies could no longer afford the costs of keeping up in the arms race afflicting Europe: ‘The present conditions cannot continue to exist forever. The peoples groan under the burdens of militarism.’

8

Where Bloch, prescient though he was, turned out to be wrong was in his assumption that even the stalemate

could not last for long; in his view European societies simply did not have the material capacity to fight wars on such a massive scale for more than a few months. Apart from anything else, the absence of so many men at the front would mean that the factories or mines would fall idle and farms would go untended. What he did not foresee was the latent capacity of European societies to mobilise and direct vast resources into war – and to bring in underused sources of labour, notably from the women.

Described by Stead as a man of ‘benevolent mien’,

9

Bloch, who was born to a Jewish family in Russian Poland and later converted to Christianity, was the closest thing Russia had to a John D. Rockefeller or an Andrew Carnegie. He had played a key role in the development of Russia’s railways and founded several companies and banks of his own. His passion, however, was the study of modern war. Using a wealth of research and a multitude of statistics, he argued that advances in technology, such as more accurate and rapidly firing guns or better explosives, were making it almost impossible for armies to attack well-defended positions. The combination of earth, shovels, and barbed wire allowed defenders to throw up strong defences from which they could lay out a devastating field of fire in the face of their attackers. ‘There will be nothing’, Bloch told Stead, ‘along the whole line of the horizon to show from whence the death-dealing missiles have sped.’

10

It would, he estimated, require the attacker to have an advantage of at least eight to one to get across the firing zone.

11

Battles would bring massive casualties, ‘on so terrible a scale as to render it impossible to get troops to push the battle to a decisive issue’.

12

(Bloch shared the pessimistic view that modern Europeans, especially those living in cities, were weaker and more nervous than their ancestors.) Indeed, in the wars of the future it was unlikely that there ever could be a clear victory. And while the battlefield was a killing ground, privation at home would lead to disorder and ultimately revolution. War, said Bloch, would be ‘a catastrophe which would destroy all existing political institutions’.

13

Bloch did his best to reach decision-makers and the larger public, handing out copies of his books at the first Hague Peace Conference in 1899 and giving lectures, even in such unfriendly territory as the United Services Institute in London. In 1900 he paid for an exhibit at the Paris Exposition to show the great differences between wars of the past and the ones to

come. Shortly before he died in 1902, he founded an International Museum of War and Peace in Lucerne.

14

The view that war was simply not rational in economic terms reached the wider European public through the unlikely agency of a man who had left school at fourteen and knocked about the world as, among other things, a cowboy, pig farmer, and prospector for gold. Norman Angell was a small, frail man who was frequently ill but who nevertheless lived to be ninety-four. Those who met him over his long career agreed that he was good-natured, kind, enthusiastic, idealistic, and disorganised.

15

He eventually found his way into journalism and worked in Paris on the

Continental Daily Mail

before the Great War. (He also found time to set up the first English Boy Scout troop there.) In 1909 he published a pamphlet,

Europe’s Optical Illusion

, which grew over many subsequent editions into the much longer

The Great Illusion

.

Angell threw down a challenge to the widely held view – the great illusion – that war paid. Perhaps conquest had made sense in the past when individual countries subsisted more on what they produced and needed each other less so that a victor could cart off the spoils of war and, for a time at least, enjoy them. Even then it weakened the nation, not least by killing off its best. France was still paying the price for its great triumphs under Louis XIV and Napoleon: ‘As the result of a century of militarism, France is compelled every few years to reduce the standard of physical fitness in order to keep up her military strength so that now even three-feet dwarfs are impressed.’

16

In the modern age war was futile because the winning power would gain nothing by it. In the economically interdependent world of the twentieth century, even powerful nations needed trading partners and a stable and prosperous world in which to find markets, resources, and places for investment. To plunder defeated enemies and reduce them to penury would only hurt the winners. If, on the other hand, the victor decided to encourage the defeated to prosper and grow, what would have been the point of a war in the first place? Say, Angell offered by way of example, that Germany were to take over Europe. Would Germany then set out to ransack its conquests?

But that would be suicidal. Where would her big industrial population find their markets? If she set out to develop and enrich the

component parts, these would become merely efficient competitors, and she need not have undertaken the costliest war of history to arrive at that result. This is the paradox, the futility of conquest – the great illusion which the history of our own Empire so well illustrates.

17

The British, so he argued, had kept their empire together by allowing their separate colonies, notably the dominions, to flourish so that all had benefited together – and without wasteful conflict. Businessmen, Angell believed, had already realised this essential truth. In the past decades, whenever there had been international tensions which threatened war, business had suffered and as a result, financiers, whether in London, New York, Vienna or Paris, had got together to put an end to the crisis ‘not as a matter of altruism, but as a matter of commercial self-protection’.

18