The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 (82 page)

Read The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 Online

Authors: Margaret MacMillan

Tags: #Political Science, #International Relations, #General, #History, #Military, #World War I, #Europe, #Western

Among the ministers attending was the Prime Minister of Hungary, István Tisza, who took a hard line and who, in the crisis of 1914, was going to play a crucial part in Austria-Hungary’s decision to go to war with Serbia. His compatriots, even those who were his political enemies, regarded Tisza with awe for his courage, his determination, and his wilfulness. ‘He is the smartest man in Hungary,’ said a leading political opponent, ‘smarter than all of us put together. He is like a Maria Theresa commode with many drawers. Each drawer is filled with knowledge up to the top. However, what is not in those drawers does not exist, as far as Tisza is concerned. This smart, headstrong, and proud man is a threat to our country. Mark my words, this Tisza is as dangerous as an uncovered razor blade.’

100

Franz Joseph liked him because he was able to deal firmly and effectively with the Hungarian extremists who thought only of Hungary’s independence and who had been blocking all attempts in the Hungarian parliament to get increases in the military budget.

Tisza, who had been Prime Minister once before, was at once a strong Hungarian patriot and a supporter of the Habsburg monarchy. Hungary had an advantageous position, in his view, inside Austria-Hungary which protected it from its enemies such as Rumania and allowed the survival of the old Hungarian kingdom with its large territories. Deeply conservative, he was determined to maintain both the commanding position of his own landed class and the dominance of Hungarians over their non-Hungarian subjects including Croatians, Slovaks, and Rumanians. Universal suffrage, which would have given the minorities a say in Hungary’s politics, would, he said, amount to ‘castrating the nation’.

101

In foreign policy, Tisza supported the alliance with Germany and regarded the Balkan states with suspicion. He would have preferred peace with them but was prepared for war, especially if any of them became too strong.

102

In the Common Ministerial Council he supported an ultimatum to Serbia to withdraw its forces from Albania. He wrote privately to Berchtold: ‘Events on the Albanian-Serbian border

make us confront the question whether we will remain a viable power or if we will give up and sink into laughable decadence. With every day of indecision we lose esteem and the chances of an advantageous and peaceful solution become more and more compromised.’ If Austria-Hungary missed this chance to assert itself, Tisza went on, it would rightly lose its place among the great powers.

103

On 18 October Austria-Hungary issued its ultimatum to Serbia and gave it eight days to comply. Among the great powers, only Italy and Germany had been informed ahead of time, yet another indication that the Concert of Europe was ceasing to exist and in the next months the Triple Entente and the Triple Alliance increasingly worked separately when it came to Balkan issues.

104

Neither of its allies opposed Austria-Hungary’s move and Germany went further and gave its firm support. The Kaiser was especially vehement: ‘Now or never!’ he wrote on a letter of thanks from Berchtold. ‘Some time or other peace and order must be established down there!’

105

On 25 October, Serbia capitulated and moved its troops out of Albania. The following day the Kaiser, who was on a visit to Vienna, had tea with Berchtold and told him that Austria-Hungary must continue to be firm: ‘When His Majesty Emperor Francis Joseph demands something, the Serbian government must give way, and if it does not then Belgrade will be bombarded and occupied until the will of His Majesty is fulfilled.’ And gesturing towards his sabre, Wilhelm promised that Germany was always ready to support its ally.

106

The year of crises in the Balkans ended peacefully but it left behind a fresh crop of resentments and dangerous lessons. Serbia was a clear winner and on 7 November it gained yet more territory when it signed an agreement with Montenegro to divide the Sanjak of Novi Bazar. Serbia’s national project was still, however, unfinished. There was now talk of union with Montenegro or the formation of a new Balkan League.

107

The Serbian government was incapable and largely unwilling to rein in the various nationalist organisations within Serbia which were agitating among the South Slavs within Austria-Hungary. In the spring of 1914 during the celebration of Easter, always a major festival in the Orthodox Church, the Serbian press was filled with references to Serbia’s own resurrection. Their fellow Serbs, said a leading newspaper, were languishing within Austria-Hungary, longing for the freedom that

only the bayonets of Serbia could bring them. ‘Let us therefore stand closer together and hasten to the assistance of those who cannot feel with us the joy of this year’s feast of resurrection.’

108

Russia’s leaders were concerned about their headstrong small ally but showed little inclination to rein it in.

In Austria-Hungary, there was satisfaction that the government had finally taken action against Serbia. As Berchtold wrote to Franz Ferdinand shortly after Serbia bowed to the ultimatum: ‘Europe now recognizes that we, even without tutelage, can act independently if our interests are threatened and that our allies will stand closely behind us.’

109

The German ambassador in Vienna had noticed, however, ‘the feeling of disgrace, of restrained anger, the feeling of being mucked about by Russia and its own friends’.

110

There was relief that Germany had in the end remained true to the alliance but resentment at Austria-Hungary’s growing dependency. Conrad complained: ‘Now we are nothing more than a satellite of Germany.’

111

To the south, the continued existence of an independent Serbia, and one now more powerful than before, remained as a reminder of Austria-Hungary’s failures in the Balkans. Berchtold was widely criticised by the political representatives of Austria and Hungary and in the press for his weakness. When he offered to resign at the end of 1913, Franz Joseph was unsympathetic: ‘There is no reason, nor is it permissible to capitulate before a group of a few delegates and a newspaper. Also, you don’t have a successor.’

112

Like so many of his colleagues, Berchtold remained obsessed with the menace from Serbia and with Austria-Hungary’s great-power status, which he saw as intertwined. In his memoirs he tellingly talks about how the empire had been ‘emasculated’ in the Balkan wars.

113

Increasingly, so it seemed, Austria-Hungary faced a stark choice between fighting for its existence or disappearing from the map. Although Tisza initially had floated improbable schemes to work with Russia to persuade Serbia to give up some of its gains, by this point most of the leadership in Austria-Hungary had abandoned hope that Serbia could be won over peacefully; it would only understand the language of force. Conrad, the new War Minister General Alexander Krobatin, and General Oskar Potiorek, the military governor of Bosnia, all were convinced hardliners. The Common Finance Minister, Leon von Biliński, who had tried to keep Austria-Hungary’s finances on an even keel, now

supported greatly increased military spending. ‘A war would perhaps be cheaper’, he said, ‘than the present state of affairs. It was useless to say we have no money. We must pay until a change comes about and we no longer have almost all of Europe against us.’

114

It was also now widely accepted among the top leadership that a showdown with Serbia and possibly with Russia could not long be postponed, although Conrad continued to believe until the eve of the Great War that Russia might tolerate a limited Austrian-Hungarian attack on Serbia and Montenegro.

115

The one man who still hoped to avert war was Franz Ferdinand.

In the year from the outbreak of the First Balkan War to the autumn of 1913, Russia and Austria-Hungary had come close to war on several occasions, and the shadow of a more general conflict had fallen across Europe as a whole as their allies had waited in the wings. Although the powers had in the end been able to manage the crises, their peoples, leaders and publics alike had become accustomed to the idea of war, and as something that might happen sooner rather than later. When Conrad threatened to resign because he felt he had been snubbed by Franz Ferdinand, Moltke begged him to reconsider: ‘Now, when we are moving towards a conflict, you must remain.’

116

Russia and Austria-Hungary had used preparations for war, especially mobilisation, for deterrence but also to put pressure on each other, and, in the case of Austria-Hungary, on Serbia. Threats had worked this time because none of the three countries had been prepared to call the bluffs of the others and because, in the end, the voices for maintaining the peace were stronger than those for war. What was dangerous for the future was that each of Austria-Hungary and Russia was left thinking that such threats might work again. Or, and this was equally dangerous, they decided that next time they would not back down.

The great powers drew a sort of comfort from the fact that they had muddled through yet again. Over the past eight years, the first and second Moroccan crises, the one over Bosnia, and now the Balkan wars, had all threatened to bring about a general war but diplomacy had always averted it. In these most recent months of tension, the Concert of Europe had more or less survived and Britain and Germany had worked well together to find compromises and to restrain their own alliance partners. When the next Balkan crisis came, in the summer of 1914, Grey at least expected that the same thing would happen again.

117

The peace movement which had watched with apprehension also breathed a sigh of relief. The great emergency congress of the Second International at Basle in the late autumn of 1912 had seemed to mark a new high point in co-operation in the cause of peace across national boundaries. In February 1913, the French and German socialists issued a joint manifesto condemning the armaments race and pledging to work together. Surely, so pacifists thought, the anti-war forces were growing even within capitalism and better relations among the powers were just over the horizon.

118

To bring home the horrors of war, a German film maker took footage during the Second Balkan War. His film was just starting to be shown by peace societies across Europe in the summer of 1914.

119

The new Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, which had been generously endowed by the American millionaire Andrew Carnegie, sent a mission made up of Austrian, French, German, British, Russian, and American representatives to investigate the Balkan wars. The Commission’s report noted with dismay the tendency of the warring peoples to portray their enemies as subhuman and the all too-frequent atrocities committed against both enemy soldiers and civilians. ‘In the older civilizations’, the report said, ‘there is a synthesis of moral and social forces embodied in laws and institutions giving stability of character, forming public sentiment, and making for security.’

120

The report was issued early in the summer of 1914, just as the rest of Europe was about to learn how fragile its civilisation was.

CHAPTER 17

Preparing for War or Peace: Europe’s Last Months of Peace

In May 1913, in the brief interlude between the first two Balkan wars, the cousins George V of Britain, Nicholas II of Russia and Wilhelm II of Germany met in Berlin for the wedding of the Kaiser’s only daughter to the Duke of Brunswick (who was also related to them all). Although the bride’s mother reportedly cried the whole night of the wedding at being parted from her child, the occasion was, so Sir Edward Goschen, the British ambassador, told Grey, a ‘splendid success’. The Germans had been extremely hospitable and the king and queen had enjoyed themselves thoroughly. ‘His Majesty told me that He had never known a Royal visit at which politics had been so freely and thoroughly discussed, and He was glad to be able to inform me that He, the King and the Emperor of Russia had been in thorough agreement on all the points which they had had under review.’ The cousins were in particular agreement that Foxy Ferdinand of Bulgaria – ‘to whom His Majesty applied a strong epithet’ – must be kept under control. ‘My impression’, Goschen concluded, ‘is that the visit has done real good and that its effect will perhaps be more lasting than is usually the case with State visits of foreign Sovereigns.’

1

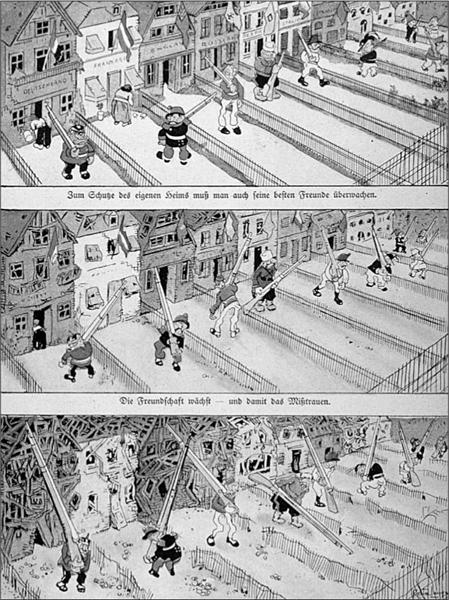

17. The last years before the Great War brought an intensifying arms race. Although moderates and supporters of the peace movement pointed to the dangers of the increasing preparations for war and complained of the increasing costs, European nations were now so suspicious of each other that they dared not back down. The cartoon shows a prosperous row of houses, bearing different national flags, becoming more and more dilapidated while the caption reads ‘The more the nations try to outdo their neighbours in the arms race, the more their own people suffer …’