The Way Into Chaos (42 page)

Read The Way Into Chaos Online

Authors: Harry Connolly

Mahz preferred to ride on the back of an okshim herd but, she said, the girls would have to make do with a raft.

Cazia was not allowed to work during the trip. The princess explained that she had paid for this escort, and they needed only walk along--or ride atop the herd or in the wagon, if they liked.

But Cazia, who had received every meal, every stitch of clothing, and every stick of firewood from her father’s most powerful enemy, suddenly felt uncomfortable. She felt she ought to contribute--not as a servant, obviously, but something. She felt unfairly singled out and pampered, as though the clan was making her last days on The Way as sweet as possible.

It was different for the princess. Every Ozzhuack approached the girl at some point in their journey to ask about the Indregai serpents. Some came two or three times, asking the same questions over and over.

Ivy reassured them with the same phrases over and over: the serpents were allies, they kept to themselves, they ate chickens and other small animals but nothing as large as a man, they only attacked when provoked. They were not big enough swallow a full-grown human, no matter what the stories said. Cazia thought the girl had more patience than any ten people, and asked her about it over an evening meal.

The princess shrugged. “They are just frightened, and it is a ruler’s duty to calm the fears of the subjects.”

“Oh!” Cazia said. It hadn’t occurred to her that the girl was adding the Ozzhuacks--along with their herd and whatever wealth they carried--to her own people. Great Way, she’d even given them a message to deliver to ensure they could end their journey at Goldgrass Hill, if they wanted.

“Besides,” Ivy said. “It is for the good of them. It’s silly for them to fear the serpents when fleeing into Peradaini lands would be a death sentence.”

The princess was once again deciding what was best for other people, but at least she was persuading them rather than tricking them.

On the ninth day, they passed a granite hut with a sleepstone inside it. After some discussion, they stopped for the night so one of the children could sleep off a sprained ankle. Late on the eleventh day, the herd crested a rounded hill and started down into a marshy basin. Not just a marsh, she realized. It was a wide, shallow lake. There were small islands here and there--little more than humps, really--that a tall man could not lie across without getting his hair and heels wet, and each sprouted a bare, twisted tree, with cattails growing where the land slipped below the water. As the sun set behind them, Cazia watched the shadows of the trees stretch across the rippled surface of the water.

On the twelfth day, at the water’s edge, the herd came to a tattered wooden dock. At Hent’s instruction, two warriors went into the shallow water and lifted rocks from the lake bed onto the dock. Cazia wondered what odd custom she was seeing until the raft bobbed to the surface.

“Still sound!” one of the warriors called from the hip-deep water.

“Here we part,” Mahz said. She gestured toward the stream flowing northward toward the long lake. “Coftin River is fresh water, not salt, so you can drink from it and shelter beneath trees at the shoreline.”

“Or in them,” Hent added.

“In them is always better when you’re alone. Remember that alligaunts prefer fresh to salt, but will hunt in both.”

“We have each other,” Ivy said. “And I have traveled through the Sweeps before.”

With an army,

Cazia could have added, but she didn’t.

As the herd began to wade through the marsh into the lake, Ozzhuacks leaped onto the okshims’ back. Neither girl made a move to get onto the raft while they were in sight; Cazia didn’t know why Ivy waited, but she herself didn’t want Hent, Mahz, or any of the others to see her fall into the water.

As the last of the herd splashed into the shallows, they heard a whip crack. Cazia started in surprise; the herders didn’t whip their okshim. She looked across the moving dark mass and saw a warrior--the young woman who had pestered Ivy the most--putting a short lash to a young girl with unkempt dark hair. Cazia’s hand went to her translation stone. “How dare you!” the warrior shouted, punctuating each word with a swing of her arm. “How dare you splash mud on me!”

Just as Cazia noted the similarity between the girl and the boy who had brought the skewers to Hent on their first night, he appeared, shielding her with his body. “Leave my sister alone!”

The young warrior immediately lost her temper. She raised her lash again. The boy leaped forward and snatched it from her hand, then threw it down between the undulating backs of the okshim.

Now several other warriors rushed to the back of the herd, moving with surprising speed and assurance. They leveled their spear points at the two dark-haired servants and shouted.

The dark-haired girl lay sprawled on one of the okshim. Her brother helped her up and they retreated together toward the back of the herd, then leaped from the last of the animals, plunging into the water.

Just a pretext, Cazia realized. The Ozzhuacks worked, slept, and ate while muddy, and no one seemed to care. If that girl was being whipped, it must have been a pretext for some other reason, and if there was one thing Cazia’s life had taught her to recognize, it was that.

The two of them swam through the muddy lake water, pulling themselves ashore near the long grasses. Ivy said. “We should probably—”

The girl cried out. Now that they were only a few paces away, Cazia could see that she was slightly older than her brother. She had, maybe, a year on Cazia, although of course she had spent more time working in the sun. Both looked slender and strong. Both wore their hair oiled and braided. The boy stood.

He looked directly at Cazia and Ivy--not in a hostile way--then looked all around. He was searching the landscape and the girls were just another part of it. There was nothing to see. He crouched beside his sister, stroked her hair once, then stood as if he’d made up his mind.

He stalked across the marshy ground and fell onto his knees in front of the two girls. He held up his open hands, his head bowed, and said, “Accept us as your servants, and we will care for you in the wilderness. Do not abandon us here.” Great Way, he was so beautiful.

Ivy turned to Cazia. “What do you think he wants?”

He clapped his hands together, then held them up again. Ivy said something in another language, but when he didn’t respond, she tried another. He looked up at them, his expression apologetic. He couldn’t understand.

“Take us with you, please!” the boy said. “You do not understand me, do you? Are my gestures not enough?”

“Smile at them!” his older sister called.

“I am smiling!” he called back, and yes indeed, he was. His smile was bright and his eyes twinkled; Cazia’s skin tingled when he looked at her.

The boy ran to the dock and leaped into the water beside the raft. After a quick examination, he shook it by the corner. He immediately waved the girls over, calling, “You see? This is not safe! We can help you.” Cazia and Ivy stepped cautiously onto the dock to see what he was doing.

He pointed to the corner and pushed the raft back and forth in the water. The narrow logs clacked against each other--clearly, they weren’t tightly lashed together.

Cazia turned to Ivy. “Still sound,” she said, her tone sour. So much for Ozzhuacks repaying their kindness.

The boy pulled the raft onto the muddy bank. He said, “Let us begin,” to his sister, and she followed him into the tall reeds. Within a few breaths, they had gathered enough reeds that they began twining them together. Soon, they began to wrap the raft more tightly.

He kept saying, “We can help. You will see,” over and over, his tone assuring, and he smiled up as he said it.

Cazia’s heart skipped. Great Way, he was

beautiful.

She stepped back and turned away, letting go of the translation stone. What did he think of her, in her muddy hiking skirts and jacket and tangled hair? Not much, she was sure, no matter how bright his smile.

And anyway, who did he think he was, making her respond so powerfully? She could never trust someone like that.

It was near midday when they finally finished working on the raft. The timbers had been bound so tightly that they no longer knocked together or twisted.

Ivy turned to Cazia. “I do not suppose we can just leave them.”

“I don’t suppose we should take them, either,” Cazia said, knowing very well that at the moment she sounded even more petulant than a twelve-year-old princess. “Mahz and Hent and the rest think this is suicide, but they want to go with us? I don’t trust them.”

“Really?” Ivy sounded honestly surprised. “Why? Did they say something alarming? Is it because they were driven away from the Ozzhuacks?”

Because he made me feel something I wasn’t ready to feel.

“How could I know what they said? I don’t understand their language.” Ivy looked a little chastened, but just a little. “I don’t trust them, because we don’t know anything about them! Servants aren’t interchangeable, you know.”

“If we do not take them,” Ivy said, “they will have nowhere else to go. No clan. I am pretty sure they are Poalos, and—”

“Poalos!” The boy exclaimed. He pointed at his heart, then at his sister’s heart. “Poalos.”

“Yes,” Ivy said. “That is right.” She turned to Cazia. “Mahz said the people had been destroyed. Without a clan, how are they supposed to survive? Just the two of them?”

Cazia and Ivy made two, of course, and were even younger than the herders; such extraordinarily subtle hints weren’t wasted on her. “How is that our fault?” Cazia knew she sounded peevish but she couldn’t help it. “Besides, shouldn’t they be married or something? Mahz offered me a husband, but not them?”

Ivy shrugged. “They are probably cousins. Among the Ergoll, if you take in your own family, you cannot marry them to make them work, so they become Men—I mean, servants.”

Would the four of them really be safer than a pair? Cazia wanted to argue the point, but she couldn’t think of anything that she wouldn’t be embarrassed to say aloud. “Fine. But I don’t trust them, Ivy.” She lowered her voice. “Let’s treat them like spies.”

“All right, then; I will not trust them, either. Not until you do.” Ivy turned to them, nodded her head once, then set her backpack on the ground. She pointed first at the pack, then the raft.

Grinning broadly, the boy leaped forward to carry their packs onto the raft.

The Poalos were too pleased to be accepted as servants. Servants in the palace--the most prestigious place in the world to work--had always seemed sullen and resigned, if not outright resentful. She hadn’t blamed them for being unhappy, of course, but it was still unpleasant.

In contrast, the siblings seemed grateful and eager to please. They set Cazia’s and Ivy’s backpacks in the center of the raft, arranged so the girls could sit atop them. Ivy kept her spear upright and ready, so Cazia did the same. The Poalos used long poles to push away from the dock toward the okshim herd.

The princess was startled at first, but Cazia knew where they were going. The Ozzhuacks had thrown the Poalos’ things from the back of the wagon, piling them beneath a tree on a muddy hump some distance away.

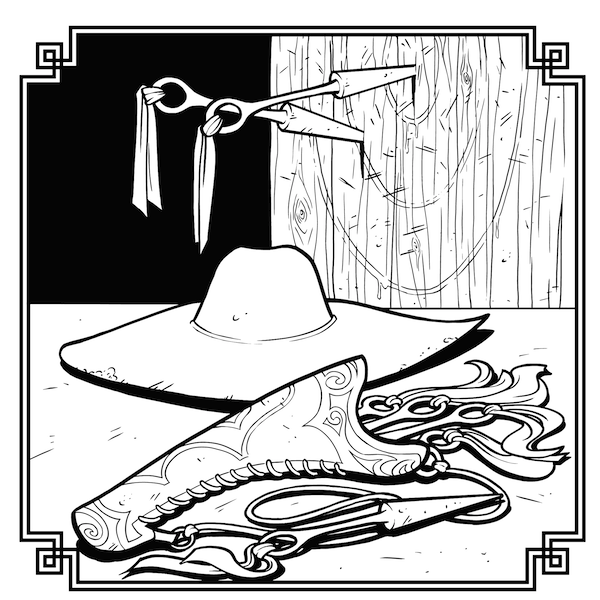

After the siblings had collected their things, including a copper hatchet and fishing spear, they let Ivy direct them downriver. The servants glanced at each other nervously, then obeyed.

The older sister was named Kinz, the younger brother was Alga and their shared family name was Chu. Cazia thought they were terrible names for two such beautiful people, but maybe they sounded better to their ears. Cazia wondered how her name sounded to them.

The Coftin River was lazy, broad, and shallow. Cazia stared straight ahead; Ivy was keeping watch, so she would, too.

But she also kept Kinz in her peripheral vision, watching her without seeming to. Once they were well beyond the dock and floating slowly toward the Northern Barrier, Cazia saw the older girl give her brother a quick, furtive look, and her smirking expression betrayed her.

They fell for it,

that expression said.

Chapter 20

By the fifth night, Cazia had become so accustomed to sleeping in trees that she almost slept through until dawn. Progress on the river was steady but slow, and that afternoon, the Poalos had dragged the raft onto a sizable island in the middle of the river. With hand gestures, they made it clear that the mud and weeds on the eastern bank would be impossible for their raft. For once, everyone had found an almost-comfortable spot in their own tree.