The Weary Generations (49 page)

Read The Weary Generations Online

Authors: Abdullah Hussein

âI can't,' Ali said his first words.

âI am not surprised,' the woman said, laughing lightly. âAt least you can speak. I saw you at Ambala station. You had an old man with you and two bundles of things. I was in the train. You tried but couldn't get on the train. Nobody could, we were already dying inside with everybody on top of us. When I saw you here at first I thought you were dead. There are so many dead lying around. The second time I was there today you had turned over in your sleep and I recognized you. I bent down and saw that you were breathing. I go to the station every day to look for my son. We were together but got separated when the train was attacked at Amritsar. I know he is alive. He is only six, but he is clever. I will find him one day. See, you can swallow if you really try, you have half a cup of milk inside you. You will be all right. Now you can go back to sleep. Here, lie yourself down on this quilt, it's soft, give your bones a rest.'

The woman tended to Ali in her hut, gradually getting solid food down his throat over several days. The second time Ali opened his mouth it was to answer the woman's question about his name.

âAli,' he said.

âMy name is Bano,' she said.

By the fourth day Ali could sit up on his own, and on the seventh he walked.

âWhat do you do?' was the next thing he asked.

âClean houses. What did you do in your home over there?'

âWorked with electricity.'

âWorked with electricity? What's that?'

âI mend electricity.'

The woman laughed out loud.

âWhy do you laugh?' Ali asked her.

âI have never seen electricity,' she said.

âYou clean houses, have they no electricity?'

âThey have. But I can't touch it.'

âWhy not?'

âNot allowed to.'

âI can get work,' Ali said suddenly.

âWhat work?'

âElectricity work.'

âFor money?'

âI will get money for it. I did it here before.'

âHere? When?'

âSome years ago.'

âYou know this city?'

âYes. All of it.'

âAnd me a stranger here bringing you home from the station!' Bano said, her eyes mockingly wide. âI don't believe it!'

For the first time in weeks, Ali laughed.

âYou are not strong enough,' Bano said to him. âWait some more. You can give me money when you earn it from â electricity?' She laughed again.

By the time a fortnight had gone by, Ali walked out of the hut. He returned after a few minutes and lay down on top of his quilt on the floor. Still weak in his legs, he also lacked the confidence to venture far on his own, although he knew all the streets and alleys of the city.

âIf you get me some clothes,' he said to Bano, âI can go out to the city.'

âI will get you clothes,' she said, a slight alarm in her voice, âbut stay here, get some food into you first.'

âAnd shoes,' Ali said.

âYes, shoes. I will try.'

Dressed in a clean shalwar-kameez and shoes a size too big that Bano got him from the owners of houses she cleaned, day by day Ali went further and further into town, finally, by the end of the month, reaching the shop where he last worked. The Hindu owner-electrician had fled and in his place was a white-haired man, fiddling with a switchboard.

âAre you a refugee?' he asked Ali.

âYes.'

âFrom where?'

âEverywhere,' Ali said, laughing a little. âMy village was near Rani Pur.'

âI am from Jalandhar. Sit down. Here.' The man handed Ali the wooden board with screwed-on switches and sockets and wires hanging out of it. âLet's see what you can do.'

Twenty minutes later, Ali handed the board back to the man.

âAll the men who knew anything here were Hindus. Can't find good men any more.' The white-haired electrician tossed Ali an eight-anna piece and told him to start coming to work at his shop the following day.

Back in the hut, Ali gave the silver piece to a wonder-struck Bano. âEight annas? For only three hours? What did you do?'

âOnly half an hour. This is just something so that I go to work every day. I will get ten rupees a month.'

âGod help me.' Bano put her hand to her mouth. âI get a rupee a month from each house and it takes me a whole day to do three houses.'

âYou get clothes and shoes too,' Ali said, laughing.

âOnly sometimes, for myself, an old shalwar-kameez or something. This was the first time I asked for a man's clothes and the begum asked me if I'd got myself a man. I told her no, they are for a poor refugee boy. There is a sick old man in the house, mad too, I think he will die soon. They gave me his clothes and shoes.'

âThey are nice clothes.' Ali said. âYou never wear clean clothes.'

âMy work is with dust and muck. What do I want to wear clean clothes for?'

âYou can wear them when you come home.'

âWhy bother for such a short time? It's dark here anyway. None of your electricity here, now or ever.'

âWhen I get my money I will give you more than you earn from cleaning. Then you can stop work.'

âNo. I would die of not working. I would die of remembering my son all the time.'

For the first time in Ali's presence, Bano began to cry. Ali took her dopatta in his hand and wiped away her tears.

âHe will come,' he said to her. âI am sure he will come. As you say, he is clever. Where is his father?'

âI don't know,' Bano said. âHe went away after a while.'

âWhere was your home?'

âNowhere, although we lived in a village in Bihar when I was small.'

There was silence in the hut for a few minutes. âTell me more,' then Ali said to her.

âWhat is there to tell?'

âTell me how you lived.'

âMy mother and father died when I was young. My brother and I lived in other people's houses. After some time Madan, he was my brother, ran away. I was ten, old enough to start working in houses, all cleaning work, we were cleaning people, not allowed to touch any other thing. My brother returned one day and took me away with him. He had fallen in with some wild people. They were outlaws, mixed up with dangerous things. We wandered from place to place. Many new people came to stay with us and then went. One time my brother went out and did not return. It was like that with those people. They were looking for death. I ran away from there. I did not like cleaning homes so I got work in shops and factories, still cleaning work, but at least they were shops and factories and not homes full of

women and children. There I met Kamal. He was half owner of a shop. I liked him. He said he would marry me if I became a Muslim. I didn't know about these things. He only asked me to repeat some holy verses after him and changed my name to Bano. After my son was born my husband took up with another woman and went away. I wasn't angry with him. But I knew I had made a great mistake. Not by marrying him but changing my religion. If I hadn't done that I wouldn't be a refugee today. But I am not angry with him or me. I made a mistake for love.'

âYou don't like cleaning homes?'

âNo. I am doing it because there is no other work here. But I keep looking. One day I will get work in a shop or a factory, in a big shop or a big factory. I can do hard work.'

âWhen I start getting money from my job,' Ali said, âI will give you all of it.'

âYou don't have to. I will get my own work in a big place.'

It was late at night. The last of the monsoon clouds were hovering above the earth, thundering in the distance. With clean clothes on him and a half rupee that he had earned and given to Bano, Ali's heart was big.

âYour clothes are dirty,' he said to her. âGo and change them.'

âWhat, now?'

âYes. Go on.'

Bano got up and went a few feet to the other wall of the hut where her bundle of clothes lay. She pulled out a shalwar-kameez from the bundle. Turning her back to Ali, she quickly took off her kurta and shalwar and put on the thin white silken suit. But Ali had had a glimpse of the straight body of a woman who was perhaps ten years older than him but who had a sinewy, arched back and slim hips with not an ounce of fat on them, moulded by a lifetime's toil as though cut from black stone. She came back to sit by him.

âIs it all right now?'

âYes,' Ali said, looking at her with unblinking eyes. She looked back.

âYou should eat more if you want to go to work every day,' she said to him.

âI will,' he said.

The flame on the wick of the lantern began to flicker, indicating the last of the oil. Bano reached out to blow it out. She did not go to her side of the hut but lay down beside Ali on the soft quilt on the ground.

âYou can keep your money,' she said to him in the dark, âbut don't go away after a while.'

âI won't,' he said.

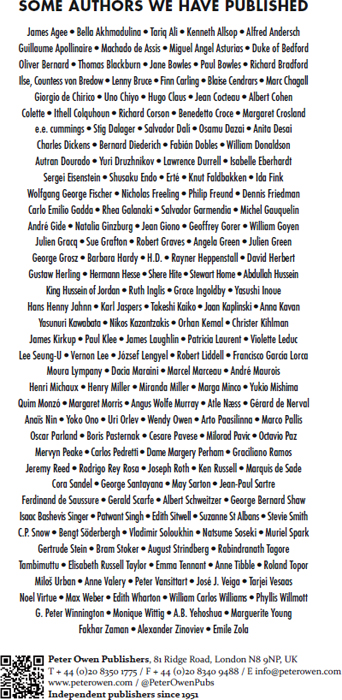

PETER OWEN PUBLISHERS

81 Ridge Road, London N8 9NP

Peter Owen books are distributed in the USA by

Independent Publishers Group/Trafalgar Square

814 North Franklin Street, Chicago, IL 60610, USA

UNESCO Collection of Representative Works

Translated from the Urdu

Udas Naslein

First English-language edition

published in Great Britain 1999 by

Peter Owen Publishers

This ebook editon 2014

© Abdullah Hussein 1963

© UNESCO 1999 for the English translation

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the written permission of the publishers.

PAPERBACK ISBN 978-0-7206-1062-1

EPUB ISBN 978-0-7206-1771-9

MOBIPOCKET 978-0-7206-1772-6

ISBN PDF ISBN 978-0-7206-1773-3

A catalogue for this book is available from the British Library

Independent publishers since 1951