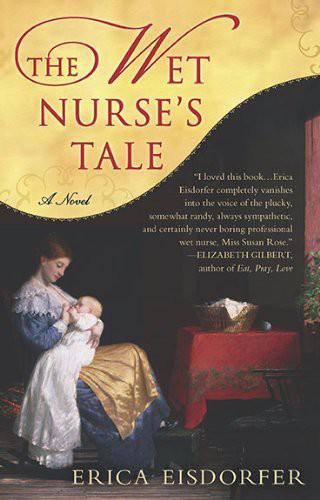

The Wet Nurse's Tale

Read The Wet Nurse's Tale Online

Authors: Erica Eisdorfer

Tags: #Family secrets, #Mothers and sons, #Historical, #Great Britain - History - Victoria; 1837-1901, #Family Life, #General, #Historical Fiction, #Wet Nurses, #Fiction

Table of Contents

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

Publishers Since 1838

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA •

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3,

Canada (a division of Pearson Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London

WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland

(a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road,

Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) •

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park,

New Delhi-110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale,

North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Copyright © 2009 by Erica Eisdorfer

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned,

or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do

not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation

of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

Published simultaneously in Canada

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Eisdorfer, Erica.

The wet nurse’s tale / Erica Eisdorfer.

p. cm.

eISBN : 978-1-101-10896-3

1. Wet-nurses—Fiction. 2. Mothers and sons—Fiction. 3. Family secrets—Fiction.

4. Great Britain—History—Victoria, 1837-1901—Fiction. 5. Domestic fiction. I. Title.

PS3605.I77 W

813’.6—dc22

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of

the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons,

living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers

and Internet addresses at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author

assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication.

Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume

any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

To Sophie & Charlotte

“. . . the moral state of the nurse is to be taken into account . . .”

—FROM Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management, 1861

One

T

here was snow on the ground when my time came. I’d expected pain but, Reader! How could this be! I bellowed, I know I did.

“It’s like shitting a pumpkin, it is,” I cried.

“Shut up, if you can, girl,” said Dinah, the midwife, “for you’re hurting my ears and you’ll be fine in the end. I’m feared your baby’ll be deef with the noise you’re making.”

“I’ll never be fine in my end again,” I panted, which made her laugh herself, but then the pains started back up and so did my shrieks.

When it was all over, I cried for my mother, to think what the poor thing suffered for all of us. And then I did what I’d seen my mother do for my whole childhood, and that was to open my shift for the baby and let it nurse.

My mother told me that at first, she didn’t take in other people’s children because she wasn’t a cow now, was she? But when Father wasn’t drunk, he’d become frustrated at his wife’s constant greatness and he’d hit her. One day she took someone else’s child to nurse along with her own and she was paid for it, more than she ever made plaiting straw for hats or for selling eggs. And so she gave that money to him as a little extra and he drank it away and was a lamb for a week. She seemed to have milk for both her own and another, so why waste it, said she.

“Mother,” I said to her once, when I was small, “will I nurse a babe as you do?”

“Well, my dear,” said she, “you’ll need more than that to do it,” and she pointed at my own flat front and then laughed and hugged me to her so the baby in her arms gave a great squawk and then a belch. I recall her words for twasn’t long before I began to grow, and when I stopped, well, I could nurse the whole of England now, is how I can say it best.

My name is Susan Rose. Here I sit in a lady’s house with a lady’s babe at my breast, and it’s where I’ve been before though the house was different and the baby too. I’ve got what rich ladies need right here in front of me and I learned to do what I do by example. It’s my mother’s milk that washed me up on this shore. It has got me to places far from my own mother, and it has got me close to those I should have avoided and it has got me far from my own hopes, but I dream still. Nursing’s good for dreaming, for it takes a good deal of sitting still.

In this house, the Chandlers’ it is, I nurse a pair of little ones. I’m feeding one now and there’s another awaiting in the cradle across the room: I can hear it mewling for me already and if it wouldn’t disturb this wee one, almost asleep now, I’d get up from my chair, with him still suckling away, the dear, and fetch the next one. But it would. This one’s a persnickety little mite, and doesn’t like to be jostled once his eyes begin to droop. The girl’s different. It’s as if she’s already accustomed to waiting for her brother’s leavings and to catching sleep where she can. Of the two of them, I’d bet on her.

My mistress is the shrew, Mrs. Chandler. She hates those babies for losing her her figure, and she bids her maid lace her as tight as she can bear it, which sours her temper yet more. She bedecks the babies in cheap lace that scratches so they squall when she’s showing them and so who could wonder why they fret? Yesterday, her mother tried to say something to her about it but she’d have none of it. “Mother,” she said all high about herself, “this is Chantilly and it’s from Paris and that’s all there is to it.” Mrs. Haver, as the lady’s mother is called even by her son-in-law, catched my eye for a second but I looked away. I don’t want to lose my position even though twins are hard.

Mr. Chandler loves his wife and that’s a nice thing I can say. He’s a barrister and young but quite ugly though he’ll get better, I think. I notice things like this—how something appears now and what I think it’ll look like later on. That’s the thing of gazing at babies. It makes you right good at predicting. She’s still angry at him for filling her in the first place, is how I see it, and she hasn’t yet let him touch her, at least it doesn’t seem thus, from the way he gazes at her as if he could eat her. She’ll give in to him, I suppose, sooner or later, when she wants some bauble, or when natural urges strike her, which they will, once she stops hurting down below. Her bosom is still almost as big as my own, but those bladders will burst soon: that’s how we put it, my mum and I, though it’s not a very pretty image and I hope you’ll forgive me for it.

Mrs. Chandler’s house is not as clean as I could like. There’s often grease on my cup and on the handle of my fork. And just yesterday, I saw one of the housemaids flirting with the farrier’s boy for a whole half an hour and then give short shrift to the linen. I see a lot through that window, as I sit still at my duty. I do love a window. In my first position, I had no window, just a closet off a larger room, and to pass the time I sang. I know a lot of songs and for that I thank my mother, who sang to the ten of us every day over her own duties.