The White Horse King: The Life of Alfred the Great (2 page)

Read The White Horse King: The Life of Alfred the Great Online

Authors: Benjamin R. Merkle

Tags: #ebook, #book

By sunset, the Danes and the Picts had been entirely routed, and King Æthelstan, with his exhausted and bloodied troops, stood as the clear victor of the battle. This triumph made him the first Saxon king to be able to claim lordship over the whole of Britain, having driven the Vikings entirely from the island and having won the submission of the Picts and the Welsh. This battle also marked the end of a war against the Danish invaders that had begun many decades before Æthelstan’s birth, a war that had been fiercely fought by Æthelstan’s father, Edward, and his grandfather, Alfred.

And though Æthelstan was privileged to be the king standing victorious at that final battle, his great victory on the bloody fields of Brunanburh was only a small part of a much greater campaign waged by his predecessors. Æthelstan would be remembered for winning the “great battle,” but his grandfather, Alfred, had set into motion the events that culminated in this victory, feats that ensured Alfred would always be remembered as the great king—Alfred the Great, king of Wessex.

2

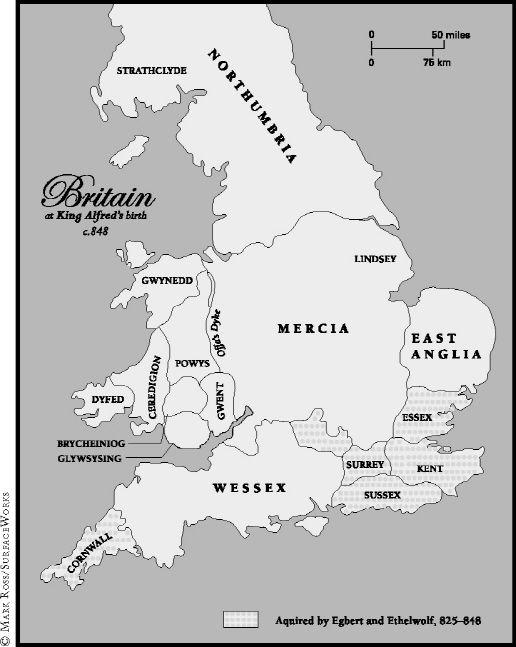

In the year AD 849, Osburh, the wife of Æthelwulf, king of Wessex (the Anglo-Saxon kingdom in the southwest of the island of Britain), gave birth to the king’s fifth son during a stay at the small royal estate in the town of Wantage on the northern edge of the Wessex border. Alfred

3

was the last child born to Æthelwulf and Osburh, his oldest brother being more than twenty years older than him. With so many brothers between him and his father’s crown, it was quite unlikely that Alfred would ever ascend to the throne of Wessex.

Alfred grew up roaming the countryside of Wessex alongside his father, who regularly journeyed throughout the many towns and cities within his kingdom. Sometimes on horse and sometimes on foot, Alfred learned the network of Wessex’s old Roman roads, still used by the Anglo-Saxons. As they visited each city, Alfred’s father and his advisors busied themselves with ensuring that the governing and taxation of the people had been competently managed. It was often a dull and dreary business. But the monotony of these bureaucratic chores was offset by the entertainments of the Saxon court.

There were the hunts, for which Alfred would have a particular fondness throughout his life. There were falconry, footraces, and horse races. There were wrestling, archery, sword fighting, and spear throwing. There were feasts with guests from afar—travelers, seafarers, experienced warriors, priests, traders, mercenaries, pagans, scholars, bishops, thieves, and princes. But most exciting of all, there were the poets. Alfred always had a particular fondness for the poetry of his native tongue. Late into the evenings, the Anglo-Saxon men would sit in the mead hall around a blazing fire, with their bellies full of roasted meat. The mead was poured out for each man from a gilded bull horn, and the enchanting thrumming of the scop

4

on his lyre began.

The songs Alfred heard in the mead hall as a boy intoxicated him. He was held in thrall by the stories of men charging grim-faced and stoic into battle. He was pierced by the lament of loss when lovers and lords were cut down by cruel blades or swallowed up by icy waves, and he quivered with a chilly awe when mortal men willingly sacrificed their lives for the sake of nobility and honor.

Alfred’s mother offered a small book of poetry to the first of her sons who could commit the volume to memory. Though the book may have been small, the gift was a treasure—a small collection of Anglo-Saxon poems, carefully handwritten on pages cut from calfskin. The opening page was dazzling, with bright colors ornamenting the first letter of the first poem. Alfred, unable to read the book for himself, was fascinated by the beauty of the volume and jumped at the opportunity. He immediately took the book and found someone who could read the poems to him so that he could commit them to memory. Soon he returned, recited the entire contents of the volume, and collected his prize.

Lindisfarne Island lies off the northeast coast of England, just south of the Scottish border. It is a tidal island—when the tide is low, a narrow causeway connects Lindisfarne to the English coast, turning the island into a bulbous peninsula attached to the Northumbrian shore. But when the tide is high, the causeway is swallowed by the North Sea, and Lindisfarne becomes an island—the thousand-acre Holy Island. It is the epitome of seclusion: cold and grey, the air chilled by wind and wave-spray, filled with the cry of gulls and a palpable sensation of northernness. The island had been made famous during the later half of the seventh century by the great bishops Aidan and Cuthbert, whose austere piety had nurtured the faith of the early Anglo-Saxon Christians and had set an example of Christian living that would become the epitome of early English godliness.

During the following century, the stories recounting the godliness of Cuthbert and the miracles wrought by his relics grew into legends, and the legends in turn were embellished into awe-inspiring epics. As the fame of those saints and their Holy Island grew, however, the spiritual discipline of the monastery they had established there sadly began to languish. First, the stricter elements of the monastic regime handed down by Aidan and Cuthbert were neglected. Then, slowly, the austerity of Lindisfarne turned to slackness, and its piety turned to worldliness. This slow decline of the Christian zeal of the monks was so gradual that, like the change in the tide on the Northumbrian coast, the shift was probably imperceptible at first. But this spiritual decline was punctuated with such a calamitous blast that the story of God’s dreadful judgment on Lindisfarne was soon more famous than the story of God’s blessing on that Holy Island.

An Anglo-Saxon historian gave this description of the year AD 793:

In the year 793 terrible portents came over the land of Northumbria, and miserably afflicted the people, there were massive whirlwinds and lightenings, and fiery dragons were seen flying in the air. Immediately after these things there came a terrible famine, and then a little after that, six days before the Ides of January, the harrowing of heathen men miserably devastated the church of God on Lindisfarne, by plunder and slaughter.

—Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

For the historian who recounted these events, as he looked back on the year 793, it was easy to interpret the significance and import of these mysterious signs. Whirlwinds and lightning, famines and dragons

5

—all nature had been summoned as a portent for the coming judgment. The description of this particular Viking raid is rather brief and gives none of the details of the notorious sacking of Lindisfarne, but a good deal can be inferred from other Viking raids.

Lindisfarne was probably chosen as a target since churches and monastic communities offered the prospect of great wealth with very little protection. In the following years, monasteries throughout Britain and Ireland would fall prey to the Viking raids. The Vikings came from the sea, arriving in a handful of their longboats with little or no warning of their approach. Their shallow-drafted ships were beached on the shore of Holy Island and then pulled far enough up the shore to be safe from the tide for several hours. The monks, merely puzzled for the moment, watched from within the walls of the monastery. Then, once the ships were secured, the Vikings turned to the monastery.

It is unlikely that they met any resistance as they approached. No barrage of arrows and spears. No shieldwall. Not even an armed guard. After gaining an easy entrance, the raiding party plundered the monastery of whatever portable wealth could be found, hacking to pieces whatever feeble resistance the monks may have made. Gold, silver, and jewels were seized and hauled back to the beached longboats, as well as any captives who might be sold on the slave market. They struck swiftly and ruthlessly, and then they quickly fled before any counterattack from a neighbouring village could be mounted. Throughout their time in Anglo-Saxon England, the secret to the Viking success would be the cunning selection of weak but wealthy targets and the hasty retreats, avoiding confrontation with the consistently slow-to-mobilize military forces.

Early descriptions of Viking attacks seized on the fact that Vikings made religious communities their targets of choice. According to the historians of the time, these marauding Northmen were pagan enemies of God, demonic forces at war with the Christian church. Some contemporary accounts describe the raiding Viking armies merely as “pagans” or “heathens.” They coated the walls of the holy places with the blood of the saints and had no regard for the sacred things of the Christian church. Modern scholarship has felt burdened to counter this bias with an attempt toward a more impartial verdict. Now it is often pointed out that the Viking’s selection of monasteries and churches for a prey was purely economic pragmatism. Christian churches simply provided the greatest possible gain at the lowest possible cost. The Viking attacks were driven not by a hatred of Christianity but by a cool and calculated evaluation of the Anglo-Saxon economy. So, considered from the perspective of the Northmen, who were not aware that the sacking of Christian holy places might be “taboo,” these were perfectly viable targets.

It is unlikely, however, that the monks of Lindisfarne were unaware of this “other perspective.” The role of the pagan raiding 11 army had been played once before on the island of Britain when, several centuries before the Viking raiders, the Angles and the Saxons themselves had crossed the English Channel. Unconverted and bloodthirsty, these once-pagan tribes had abandoned their homes in modern northern Germany and Denmark in the fifth and sixth centuries and had crossed over to the isle of Britain preying upon the weaknesses of the natives who had been left vulnerable by retreating Roman troops.

6

It was the establishment of the Christian church that turned the Anglo-Saxons away from a worldview that had been every bit as ruthless and cruel as the worldview held by the Viking raiders. The missionaries sent by Rome to Christianize the various warring Anglo-Saxon tribes had preached against and even given their lives in the fight against this very worldview.

Even after an Anglo-Saxon church had been firmly established, the English constantly had to fight the temptation to slip back into its own barbaric past, a godless past ruled by the worship of raw power. Threads of this old world-view remained woven throughout the poetry and songs of the Anglo-Saxons. There can be no doubt that when the Anglo-Saxon church named the Viking raiders

pagan

, they did not mean “people who have a different value system than we do.” They meant

pagan

in 12 its most proper sense: these raiding armies were full of warriors who acted like men without the gospel. It was a worldview known all too well to the men who named it as such, and it was a worldview they had rejected.