The Wild (21 page)

Authors: Christopher Golden

As it reached around a tree for him, he lashed out with the knife again, and this time the Wendigo screamed.

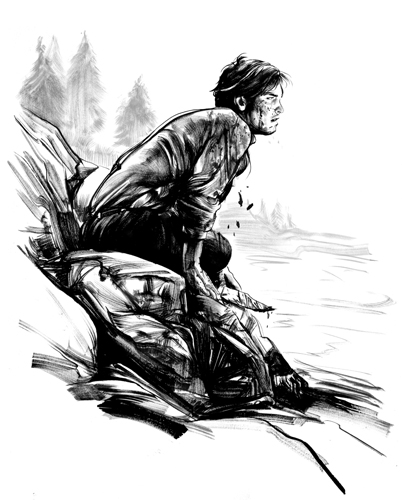

Jack gave over his reactions to instinct, casting aside conscious thought and allowing his primal nature to the fore. Most men eschewed this leftover of their animal past because they believed it beneath them, but now Jack felt the full import of his ancestors back through the ages, their thoughts, their intuitions, and their will to survive. Thousands of years behind him, wild men and women challenged nature and mastered it, and now Jack was doing the same.

The knife was his tooth and claw, speed his ally, fearlessness his drive. The threat of death was ever present, and there were no guarantees that one heartbeat would see the next. But such danger gave Jack power, because nature's prime movers were life and death.

The fight became a blur. The Wendigo screamed, and so did Jack. The sky and earth changed places, tree branches whipped across his face, the overpowering breath of the

monster dried his eyes and entered his mouth. His hand was hot with blood and the slick touch of insides. Though he still held the knife, he could no longer feel his hand on the grip, as if he and the blade were bound together.

He thrust, slashed, and stabbed, rolling across the bloodied snow that layered the ground, and feeling the land shift around him as he darted left and right, squatted down, leaped. He used the solidity of the wilderness from which to launch fresh attacks, and at one pointâminutes into the fight, or maybe hoursâthe Wendigo's scream came again, this time sounding different.

Somewhere in there, Jack heard fear.

He increased his assault, fury and rage giving way to a brutality he had never known existed within him. He was a wild man for a while, defined only by the present and giving no thought to the past or futureâhe was not Jack London, he had no family, and tomorrow was an unknown place.

At some point, Jack realized that the screaming and screeching had stopped. He was still moving across the damp, warm ground, stabbing and ducking away again, and it took him a while to realize that the ground was not the forest floor. He was soaked with sweat and blood. He could smell a fresh death. And he stood upon the tumbled corpse of the Wendigo.

Jack gasped and stood upright, looking all around. He

was standing on the monster's chest, left foot in a puddle of thick, dark blood. Around him were splayed the thing's limbs, all of them slashed and flayed, one hand almost severed at the wrist, its fingers clasped around a tree trunk and digging into the bark. To his left lay the thing's head, thrown back with its monstrous mouth open. Steam rose from the mouth. Steam also wafted from the ruin its throat and neck had become.

Something whistled, bubbles burst, and Jack heard the Wendigo's final breath.

I can be myself again now

, he thought, but he was not certain of that, because things still did not feel right. His heart thundered in his chest, and his hand refused to drop the knife. And that smellâ¦

The stench of rotting flesh was gone, and in its place the mouthwatering aroma of fresh food. Something was cookingâhe could smell its sweet, meaty aroma, the tang of sizzling fatâand beneath that, the subtler scents of roasting root vegetables. He sighed and sank down, closing his eyes, transported back to Lesya's clearing, where he watched her preparing and cooking the kill of the day. Every breath he took brought in a richer smell, and his mouth watered uncontrollably.

“I thought I was no longer hungry,” Jack whispered, but the smell of food all around him exposed the lie in

that. He must have been hungrier than he had ever thought possible. Perhaps Lesya had been starving him as well as teaching him her earthly tricks? Maybe she had only planted the suggestion of food in his mind, stripping away layer upon layer of his fat as the days went by, seeking the hollowed core of himâ¦.

All around him, the sounds of the forest started up again. There was richness in the birdcalls, and an exuberance to the rustlings and whines of small mammals from the undergrowth. Insects flew, flies buzzed, and Jack was starting to feel like the center of everything. He saw several birds perching on branches snapped during his fight with the Wendigo, and he tried to listen to the song they were singing. He stretched his mind, seeking to join in their harmony, but something dark loomed before and around him, blocking his senses and denying contact with anything outside.

“I'm Jack London,” he said, but the words seemed to hold little meaning. His stomach rumbled and roared as if in sympathy with the terrible hunger he had sensed in the Wendigo. His throat was parched.

Flesh will serve my hunger

, he thought.

Blood will quench my thirst

.

The ground was shifting beneath him, trees growing all around. He looked about in confusion for a while, and then he saw that the corpse of the defeated monster was

shrinking. Flesh and skin wrinkled and fell away. Blood pulsed from the raw meat as limbs contracted, the chest and stomach caved in, and the thing's head tilted to one side.

Soon, whatever was left of the Wendigo would be gone. Jack would have to set snares and traps, hunt a rabbit, skin and gut and cook it, and before he could do all that, maybe the hunger would take him, and he'd die an ignominious death beneath these wild skies.

But not ifâ¦

He fell from astride the shrinking corpse, reached out with his right hand, and cut a flap of bloody flesh and skin from the thing's chest. Holding it up to the light, he examined the meat. It was heavy and dark, and still dripping with rich blood. He put it to his nose, just a finger width away from his nostrils, and inhaled. It smelled sweet; uncooked, but its rawness held no dangers.

Jack sighed and opened his mouth, closed his eyes, tongue lolling.

His stomach rumbled so intensely that it hurt. He groaned and inhaled, and the sick stench of rotten flesh hit the back of his throat. Before he could prepare, he vomited, falling aside and dropping the handful of bad flesh. Vomiting again as he rolled away, Jack felt his hand open, and he discarded the knife at last. He came to rest against a tree, gasping at the sky, blinking, and then he sat up and looked

around the blood-soaked clearing.

The Wendigo lay dead at its center, and its rot was accelerating. A million flies seemed to buzz around the corpse as its flesh turned black, its skin withered, and it returned horribly to the shape of a man.

Jack had no wish to go closer and see who the man might resemble, so he scampered back to the bear cave, trying not to dwell upon what he had almost doneâ¦and almost

become

. He picked up the rifle and loaded saddlebags, groaning at the ache that had set into his muscles during the fight. The rifle was a reassuring weight again now that the Wendigo was dead, because the dangers he might face would be much more natural. He needed a drink. There was a splash of water in his canteen, and back down the hillside he'd fill up again at the river, and perhaps he'd be able to take a few shots at a rabbit on the way, skin and gut it, cook it this afternoonâ¦.

He fell to his knees.

I almost ate!

If he'd eaten the flesh of the Wendigo, he would have become one himself, a spirit cursed to haunt these wilds and prey on the innocent flesh of future travelers. His hunger would be forever, his suffering eternal, until he met someone brave and strong. Someone with a knife.

Jack had never known himself to be as wild and brutal as he'd been during his battle with the Wendigo. At the

time it had felt so right, but afterward that wildness had almost led him to eat the flesh of the vanquished. Something had stopped him, some vestige of humanity, and for that he would forever give thanks.

“I'm Jack London,” he said aloud, “and I'm a human being.” The forest answered him with a brief silence, but as he went back downhill toward the river, it returned to life. Normal, unhindered life.

Â

The storm lessened as he came to the river, and he could still see his footprints in the light snow covering from where he had been fleeing the Wendigo. It felt like weeks before, but he guessed it must have been only hours. He could see the Wendigo's prints as well, and that gave him pause. Already the chase and fight seemed like a nightmare, and to see physical evidence here of the creature's existence was shocking all over again. He looked at the blood coating his hands and trapped beneath his fingernails and wondered what would happen were he to swallow some of that. He began to panic. He could feel the crust of drying blood across his face and throat, too, and he must have taken some of it into his mouth,

must

have, when it was spraying and splashing so liberally back there in the wood.

He fell to his knees at the edge of the river and scooped up handfuls of freezing water, splashing it over his face

and head, gasping in shock at the cold but also welcoming its cleansing effect. Diluted pink splashes of blood speckled the snow around him. He washed, scrubbing his hands, scooping beneath his nails with his knife, scrubbing so hard that wounds opened in his skin. He kept washing until his own blood flowed; then he headed back along the river with his belongings, desperate to find somewhere to camp for the night that would give comfort and warmth. He needed to rest, and he needed to dry his clothes. This was not winterânot yetâbut if he was to march from the Yukon before true winter did fall, he needed to get moving.

“I'm Jack London,” he said aloud.

He enjoyed putting distance between himself and those woods. Back there, Lesya haunted her forest, and closer to him the corpse of the Wendigo still lay. Perhaps it was rotted down to nothing by now, but there would still be bones, and the ghost of its hunger would always haunt the spaces between those trees.

Feeling that his adventure here was over, Jack once again walked back to the ruined camp where he had seen the Wendigo kill so many. And before darkness fell, he uncovered the fire pit with his foot and went about rebuilding it.

OUT OF THE WILD

J

ACK WARMED HIS HANDS

against the flames, and the darkness was held at bay. This fire felt clean and fresh, and this darkness, though filled with the sounds of the wild he knew so well, carried no threat. He had faced the worst that these lands could throw at him, and he had survived.

Yet he felt no real sense of victory. Right then, he felt nothing at all. He was an injured animal licking its wounds, and shock still held him in its sway.

And his wounds were many. Once he had settled down and lit the new fire, Jack took the opportunity to examine his body in detail for the first time, and he was amazed at what he found. His hands were badly lacerated and bruised, some of the cuts possibly from his own blade, others ragged tears from thorns and snapped wood. He spent

some time picking splinters from his flesh by the flickering light of the fire, and some of them were half the length of his fingers. The pain was bright and stark, and he did not hold in his groans of discomfort.

One side of his face felt stippled with scabs, and never before in his life had he wished so much for a mirror. He could trace the wounds with his hands, but trying to place them on the face he knew so wellâyoung, impetuous, confidentâwas all but impossible. His skin felt so much older, and he knew that his expression must appear likewise.

His arms and legs were badly bruised, three of the toes on his left foot were turning dark, and most of his toenails had fallen off. His stomach rumbled. His ribs ached, and he thought perhaps he'd broken a couple. He coughed into his hand and examined the spittle beneath the firelight, taking some time to convince himself there was no blood there.

As the moon revealed itself and the stars came out, Jack at last began to shake from shock. He wrapped himself in the few blankets he had found around the ruined campâdried as best as he could before the fireâand knew that he would never be able to fall asleep.

Moments later, though, he drifted away, his head resting on the saddlebags full of gold. And as if that mystical yellow metal informed his dreams, he found himself back in better times.

Â

He knew that he was dreaming, but he had no control over the rush of images that nursed him through sleep. They were recollections from his past, and stuck here bleeding and injured in the wild lands of the north with the cold season rapidly approaching again, he recognized them as some of the most important moments of his life. Here he was walking the roads, riding the rails, and exploring America from the underbelly up. He was poor but happy. He had little but missed nothing. He met some hard people in his dream, and a few who were plain cruel, but Jack always came out the other side wiser and older, and knowing humanity more. Knowing

himself

more. This was all about growing up.

The sea rolled beneath him as he left America for the first time, venturing out into the Pacific hunting seals, blood and guts up to his knees, the clear sky glaring down at the hunters' brutal deeds, and the boys and men around him were a quiet, vicious breed. Jack kept to himself but watched them all, and in his dream he could identify each and every one of them: Jeff, the quiet man who would surprise him later with his knowledge of books; Peters, the European who only admitted to speaking English when it suited him; and the man who called himself Graybeard.

People shouted as they hunted him down, his sloop filled with poached oysters, and he knew that when they eventually

caught him he'd go over to their side and hunt oyster pirates himself. Perhaps that was a darker part of his history, and this memoryâriding the waves as he dodged the fisheries officers and plied his piracy through sea fogs and channels known only to himâwas the finer, more honest side.

He dreamed of other things, other places, and every memory made him feel better. He was reliving a harsh life well spent, filling himself once again with knowledge from beyond the wild Yukon, and in a way he thought this was his mind preparing himself for the return.

And then his dreams moved on, and he saw more. Defending the boy Hal in Dawson City. Watching in terror as the Wendigo slaughtered friends and enemies alike in the very camp where he now lay dreaming.

Lesya.

Jack shouted himself awake before the last of the dream, not wishing to reach the end in case there was no more. His life up to now had been remarkable, but there was plenty more to live, and a million places yet to see. He would not lie here and let his life play itself out across his mind, marking relevant points here and there until it reached its end. There

was

no end, not yet, and he would fight and rage against the darkness as long as he could.

He sat up and stared across the moonlit landscape, dreading the approach of death but feeling more alive than

he had in a very long time. The last time he'd felt this invigorated had been that time at the top of the Chilkoot Pass, when Merritt and Jim had first sat with him and shared coffee, with the golden future stretching out before them.

Jack piled more logs onto the fire, stood, and howled at the moon. He did not use Lesya's teachings or the traces of her magic to find his inner wolf voice but rather let it rise of its own accord. It was an exhalation of pure freedom and joy, and when it was answered from somewhere far away, Jack paused and sank slowly to his knees.

There you are

, he thought, because he recognized the voice in that reply. Wounded his spirit guide might be, but so long as Jack still drew a breath, it would always be waiting for him out here in the wild, and he needed no magic to find it, only his own heart.

Because the wild was where he had truly found his spirit.

Â

He went hunting the next morning and caught a small rabbit. He did not shoot or trap it, but simply sat still beside a fallen tree for a while, making small rabbit noises and imagining himself down there in the grass with the creatures. One of them emerged from the scrub and jumped on the tree, staring at him and wrinkling its nose as it tried to discern his scent. Before it could sniff below the pretense, Jack reached out and grabbed the creature, breaking its neck before

it knew what was happening. He experienced a moment of strange dislocation as he shed the rabbit sensesâit was as if one of his own lay dead in his lap, and a sadness crept over himâand then he returned to camp, gutting and stripping the rabbit expertly before spitting it over the fire.

As the rabbit cooked, Jack went about tidying the camp. There were shreds of the dead men's belongings scattered among the grasses, and the detritus of the massacre littered the ground. He wanted the place to be as far back to nature as was possible before he left, both in honor of the men who had died here and as acknowledgment that the Wendigo was no more. It was a part of the history of this place now, and the site of its great feeding also had to move on.

He left the saddle upon which he had scored that grim epitaph atop the pile of collected debris. It seemed a fitting marker, and though it would last no more than a year or two in these harsh climes, in his mind he would read those words forever.

Eating the rabbit seemed to purge the memory of the Wendigo's flesh from his mind. His hands were greasy with cooked meat, his stomach full of it, and his hunger was sated by the time he collected his goods and set off for Dawson City. He went east and south, determined that the shreds of civilization would be in that direction, and over his shoulders he carried the saddlebags heavy with gold.

The previous day's brief snowstorm had passed, and though snow still lay on the ground here and there, the sun was quickly melting it away. Autumn had arrived, true, but the harshest weather was still several weeks distant. For the first time in a long while, Jack felt that he was now safe, and that his immediate future was mapped out before himâa return to Dawson, a journey back across the Chilkoot pass to Dyea, then passage south to San Francisco. Once there, he would try to track down Jim's and Merritt's families, and the gold he carried over his left shoulder was for them. The gold on his rightâ¦that was for his own family. There was enough there to cover the money that Shepard had invested in the journey and, if not to get his mother out of debt, at least to stave off the moneylenders for a time. It would be plenty. Jack had other ideas about how he could benefit from his adventures.

His own terrible tales of the north he could never tell. But there were surely a million others that he could. Stories he had heard. Lessons learned. Glimpses into the heart of the wild, but not into that wild's shadows.

Around noon of that day he encountered a small group of men and women heading north. He sat and waited by a rock when he saw them, starting to build a small fire in the hope that they'd have food they would share. He kept his guns at the ready, but by the time they drew closer,

any worries had evaporated. They were stampedersâtheir gold pans rattled and swung from their packsâand their ready smiles put him at ease.

“Afternoon, friend,” one of the men called, and Jack suddenly felt his throat burning. These were the first ordinary people he had spoken to since the Wendigo attack on the camp, and that had beenâ¦how long ago? He had trouble mapping the time between then and now, but he knew it had been months.

“Afternoon,” Jack replied. “Strange time of year to be heading out from Dawson.”

“We know what we're doing,” one of the women said. She dropped her pack next to Jack, and he saw the weapons on her beltâknives, and two pistols.

“The winters up here don't much care whether you know or not,” he said. The woman glared at him, but she soon averted her gaze.

What does she see?

Jack thought.

What stares at her from these eyes?

“Only a short trip, this one,” another man said. “We been out four times from Dawson now and found nothin'. This is our last try before we head on home.”

“Good luck to you,” Jack said.

“You found any luck?” the woman asked. She glanced down at his saddlebags, then back up at his face. He smiled and she looked away again. He felt that he should not be

enjoying such power, but he couldn't help himself.

“Some,” he said. He glanced away from the group, back the way he'd come, and for a moment he pondered on luck and what it meant.

“Then can you point us the right way?” the first man asked.

“No,” Jack said. “Back that way, what little good luck there was found itself outweighed by the bad.”

The six people were quiet for a moment, shrugging their packs off and sinking to the ground. Two of them went about finishing and lighting the fire, and soon a pot of coffee was brewing. Jack handed over his metal coffee mug, and a man placed it on the ground next to their own. Jack nodded his thanks.

“You look like you've been out there for a while,” the same woman said. “Seen men like you before. Got a wild look in your eyes, like you've seen things that shouldn't be seen.”

Jack shrugged and looked into the fire.

“Seen men like that who were mad, too,” she continued.

Jack merely shrugged again, but this time he let a smile touch his lips.

Who's to say?

he almost replied, but he didn't want to alarm these people. They seemed good-natured enough, and they were sharing their coffee, but all of them carried guns. And he could see that none of them had any

inkling of the true nature of things out in the wild.

They sat together for a couple of hours, drinking coffee and talking about gold, and the wilderness, and the equally wild place that was Dawson. One of the men grabbed Jack's attention when he talked of crazy people in Dawson spending their time in the bars spouting “rubbish about flesh-eating monsters and dead men.” When Jack asked what they looked like, and whether the man knew their names, the woman asked, “Friends of yours?” That one question weighed on the atmosphere around the campfire, and it never quite recovered.

Jack was the first to rise and wish them well. He sensed eyes upon him as he lifted the heavy saddlebags, but he never once felt any threat from these people. They were like children watching an adult readying to huntâironic, considering his own youthâand Jack felt that the least he could do was spare them a word of advice.

“West is best from here,” he said. “Into the low hills.”

“We were told northwest,” the woman said. “Up into the wild forests and the valleys between mountains.”

“No,” Jack said, and he glanced at each one of them to get his message across. “Those places are cursed.” Then, shrugging off the few muttered questions that came after him, Jack turned his back on those naive explorers and went on his way.

He walked far that day, and at dusk he camped by a stream where there were the remains of several other campfires. He shot a duck and ate well, and lying beneath the stars, he listened to the night sounds closing in. None of them frightened him anymore. The cry of a wolf accompanied him into sleep, and in his mind he howled back, adding his own voice to the history of the wild.

Â

He walked from dawn to dusk the next day, coming across the remains of several camps, and the farther southeast he went, the more Dawson seemed to exert its influence. These wilds were no longer just thatâthere was a taint of humanity on the places he walked through nowâand much as he looked forward to his journey and eventual arrival back with his family, still Jack mourned the passing of this part of his life. It felt as if he were leaving a part of himself behind, and that night he sat by the campfire and howled, once more, like a wolf. There was no answering callâthe wolves kept far to the north and west of here, away from the guns of civilizationâbut neither was there a reply in his mind. He went to sleep sad that night, and he carried that same emotion with him the next morning when he approached Dawson at last.

The final sight he'd had of Dawson had been the inside of that wretched hotel room, where Archie and William

had come at him with clubs and fists. That felt like a lifetime away, but as he caught sight of Dawson in the distance, huddled beside the river at the bottom of a gently sloping valley, he knew that places like this would never change. Built on ambition and the quest for adventure, they would always be corrupted by greed and cynicism. He would enter Dawson now with his eyes open, but he swore that he would maintain hope in his heart. Not all men were bad. Merritt and Jim had shown him that.