The Wild Truth

Authors: Carine McCandless

For Chris

EPIGRAPH

I tore myself away from the safe comfort of certainties

through my love for truth; and truth rewarded me.

—Simone de Beauvoir,

All Said and Done

On September 14, 1992, I got a phone call from Mark Bryant, the editor of

Outside

magazine, who sounded unusually animated. Skipping the small talk, he told me about a snippet he’d just read in the

New York Times

that he couldn’t stop thinking about:

DYING IN THE WILD, A HIKER RECORDED THE TERROR

Last Sunday a young hiker, stranded by an injury, was found dead at a remote camp in the Alaskan interior. No one is yet certain who he was. But his diary and two notes found at the camp tell a wrenching story of his desperate and progressively futile efforts to survive.

The diary indicates that the man, believed to be an American in his late 20’s or early 30’s, might have been injured in a fall and that he was then stranded at the camp for more than three months. It tells how he tried to save himself by hunting game and eating wild plants while nonetheless getting weaker.

One of his two notes is a plea for help, addressed to anyone who might come upon the camp while the hiker searched the surrounding area for food. The second note bids the world goodbye.

An autopsy at the state coroner’s office in Fairbanks this week found that the man had died of starvation, probably in late July. The authorities discovered among the man’s possessions a name that they believe is his. But they have so far been unable to confirm his identity and, until they do, have declined to disclose the name.

Although the article raised more questions than it answered, Bryant’s interest had been piqued by its handful of poignant details. He wondered if I’d be willing to investigate the tragedy, write a substantial piece about it for

Outside,

and complete it quickly. I was already behind schedule on other writing assignments and feeling stressed. Committing to yet another project—a challenging one, on a tight deadline—would add considerably to that stress. But the story resonated on a deeply personal level for me. I agreed to put my other projects on hold and look into it.

The deceased hiker turned out to be twenty-four-year-old Christopher McCandless, who’d grown up in a Washington, D.C., suburb and graduated from Emory University with honors. It quickly became apparent that walking alone into the Alaskan wilderness with minimal food and gear had been a very deliberate act—the culmination of a serious quest Chris had been planning for a long time. He wanted to test his inner resources in a meaningful way, without a safety net, in order to gain a better perspective on such weighty matters as authenticity, purpose, and his place in the world.

Eager to receive whatever insights into Chris’s personality his family might be able to provide, in October 1992 I mailed a letter to Dennis Burnett, the McCandlesses’ attorney, in which I explained,

When I was 23 (I’m 38 at present) I, too, set off alone into the Alaskan wilderness for an extended sojourn that baffled and frightened many of my friends and family (I was seeking challenge, I suppose, and some sort of inner peace, and answers to Big Questions) so I identify with Chris to a great extent, and feel like I might know something about why he felt compelled to test himself in such a wild and unforgiving piece of country. . . . If any of the McCandless family would be willing to chat with me I’d be extremely grateful.

My letter resulted in an invitation from Chris’s parents, Walt and Billie McCandless, to visit them at their home in Chesapeake Beach, Maryland. When I showed up on their doorstep a few days later, the intensity of their grief staggered me, but they graciously answered all of my many questions.

The last time Walt or Billie had seen Chris or spoken to him was May 12, 1990, when they’d driven down to Atlanta to attend his graduation from Emory. Following the ceremony, he mentioned that he would probably spend that summer traveling, and then enroll in law school. Five weeks later, he mailed his parents a copy of his final grades, accompanied by a note thanking them for some graduation gifts. “Not much else is happening, but it’s starting to get real hot and humid down here,” he wrote at the end of the missive. “Say Hi to everyone for me.” It was the last anyone in the McCandless family would ever hear from him.

Walt and Billie were desperate to learn everything they could about Chris’s activities from the moment he performed his vanishing act until his emaciated remains were discovered in Alaska twenty-seven months later. Where had he traveled and whom had he met? What had he been thinking? What had he been feeling? Hoping that I might be able to find answers to such questions, they allowed me to examine all the documents and photos that had been recovered after his death. They also urged me to track down anyone he’d met whom I could locate from these materials, and to interview individuals who were important to Chris before his disappearance—especially his twenty-one-year-old sister, Carine, with whom he had had an uncommonly close bond.

When I phoned Carine, she was wary, but she talked to me for twenty minutes or so and provided important information for the 8,400-word article about Chris, titled “Death of an Innocent,” published as the cover story in the January 1993 issue of

Outside.

Although it was well received, the article left me feeling unsatisfied. In order to meet my deadline, I had to deliver it to the magazine before I’d had time to investigate some tantalizing leads. Important aspects of the mystery remained hazy, including the cause of Chris’s death and his reasons for so assiduously avoiding contact with his family after he departed Atlanta in the summer of 1990. I spent the next year conducting further research to fill in these and other blanks in order to write a book, which was published in 1996 as

Into the Wild.

By the time I began doing research for the book, it was obvious to me that Carine understood Chris better than anyone, perhaps even better than Chris had understood himself. So I phoned her again to ask if she would talk to me at greater length. Highly protective of her absent brother, she remained skeptical but agreed to let me interview her for a couple of hours at her home near Virginia Beach. After we started to talk, Carine determined there was a lot she wanted to tell me, and the allotted two hours stretched into the next day. At some point she decided she could trust me, and asked me to read some excruciatingly candid letters Chris had written to her—letters she had never shown to anyone, not even her husband or closest friends. As I began to read them I was filled with both sadness and admiration for Chris and Carine. The letters were sometimes harrowing, but they left little doubt about what drove him to sever all ties with his family. When I eventually got on a plane to fly home to Seattle, my head was spinning.

Before Carine shared the letters with me, she asked me not to include anything from them in my book. I promised to abide by her wishes. It’s not uncommon for sources to ask journalists to treat certain pieces of information as confidential or “off the record,” and I’d agreed to such requests on several previous occasions. In this instance, my willingness to do so was bolstered by the fact that I shared Carine’s desire to avoid causing undue pain to Walt, Billie, and Carine’s siblings from Walt’s first marriage. I thought, moreover, that I could convey what I’d learned from the letters obliquely, between the lines, without violating Carine’s trust. I was confident I could provide enough indirect clues for readers to understand that, to no small degree, Chris’s seemingly inexplicable behavior during the final years of his life was in fact explained by the volatile dynamics of the McCandless family while he was growing up.

Many readers did understand this, as it turned out. But many did not. A lot of people came away from reading

Into the Wild

without grasping why Chris did what he did. Lacking explicit facts, they concluded that he was merely self-absorbed, unforgivably cruel to his parents, mentally ill, suicidal, and/or witless.

These mistaken assumptions troubled Carine. Two decades after her brother’s death, she decided it was time to tell Chris’s entire story, plainly and directly, without concealing any of the heartbreaking particulars. She belatedly recognized that even the most toxic secrets could possibly be robbed of their power to hurt by dragging them out of the shadows and exposing them to the light of day.

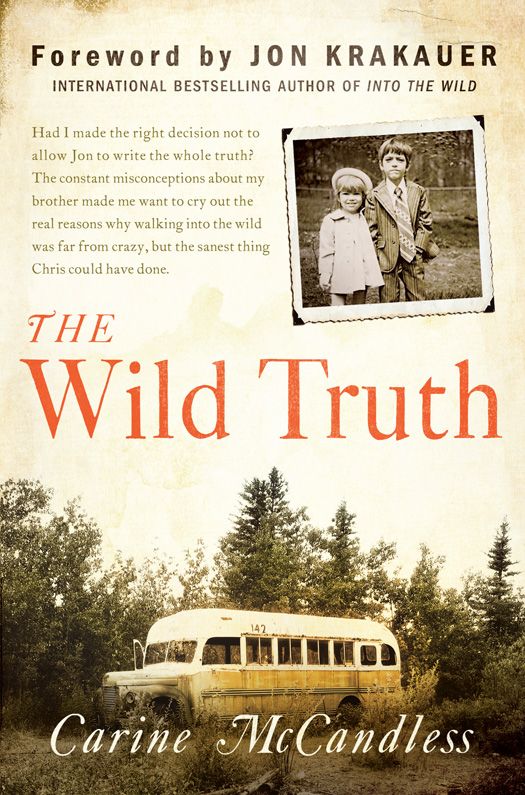

Thus did she come to write

The Wild Truth,

the courageous book you now hold in your hands.

Jon Krakauer

April 2014

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

—George Santayana,

The Life of Reason:

Reason in Common Sense

T

HE HOUSE ON WILLET DRIVE

looks smaller than I remember. Mom kept the yard much nicer than this, but the haunting appearance of overgrown weeds and neglected shrubs seems more appropriate. Color returns to my knuckles as I release the steering wheel. I hate this fucking house. For twenty-three years I managed to steel myself while passing these familiar exits of Virginia’s highways. Several times I wrestled with the temptation to veer off, wanting to generate memories of time spent with the brother I miss so terribly. But pain is a cruel thief of childhood sentiment. People think they understand our story because they know how his ended, but they don’t know how it all began.

Once a carefully tended mask, the house’s facade now appears to have been abandoned. Unruly thickets of sharp holly stab at the foundation, their berries like droplets of blood drawn from its bricks. The wood siding sags, forgotten and pale, lifeless aside from the mildew creeping across its seams. Gone are the manicured flower beds; the front yard is now adorned with random papers and bottles from passersby. It’s as if the dwelling has utterly expired, worn out from too many years as the lead in a grueling play.

The knot in my stomach quickly transforms into nausea, and I scramble out into the crisp October air to hunch over and wait, patiently. But the relief doesn’t come.