The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (17 page)

Read The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America Online

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

Truth be told, Roosevelt—as of 1874—didn’t have the self-confidence or the desire to date with marriage in mind. He was busy just trying to understand his father’s expectations. The awkward Roosevelt, who was five feet eight inches tall and weighed 124 pounds, strove to improve himself in every way. He grew bushy side-whiskers, developed compact forearms, and wore pressed clothes fit for a sportsman hunting. He always looked as if somebody had slapped the creases out of the fabric for the sake of upholding the family name. Although his parents often straitjacketed Theodore in formal attire, he preferred dressing down like a muskrat trapper or stable keeper; this fashion attitude would change at Harvard.

Visiting Edith at her summer home at Sea Bright, New Jersey, for a week in July 1874, Roosevelt noted that the sand dunes of the barrier beach were brimming with “ornithological enjoyment and reptilian rapture.”

15

Playing a Darwinian biologist, he pickled in jars all the toads, frogs, and salamanders he caught for more careful study of their evolutionary stages. Romance with Edith was put on a back burner in favor of writing about New Jersey’s avians in his

Notes on Natural History

. “Whether inland or on the coast the most conspicuous bird was the fishawk,” he wrote. “It was most plentiful by ponds, and over one of these several pairs of singular birds could almost always be observed, circling through the air on almost motionless wings, usually far out of gunshot range. On a suitable fish

being seen, the hawks swoops down with arrow like swiftness, causing a whistling, booming sound as it descended, and stooping with such force as sometimes to totally immerse itself in water.”

16

With the hungry speed of youth, Roosevelt was dead certain about his career direction. As his father conceded when they returned from the trip to Europe and the Middle East, he was predisposed to be a scientific naturalist or wildlife biologist. But Theodore Sr. warned his son that a life of science meant long hours in a sterile laboratory; field collecting was only a small part of the profession. Either way, the importance of being accepted at Harvard weighed greatly on young Theodore. When word of his acceptance came in the spring of 1876, he was elated, but he also knew that the time had come to professionalize his infatuation with animals. “When I entered college, I was devoted to out-of-doors natural history, and my ambition was to be a scientific man of the Audubon, or Wilson, or Baird, or Coues type,” Roosevelt recalled in

An Autobiography

, “a man like Hart Merriam, or Frank Chapman, or Hornaday, to-day.” The key phrase here is “out-of-doors” he didn’t want to be an indoor scientist, the kind of scientist Captain Reid had shunned.

17

Throughout the summer of 1876, as America was in the midst of celebrating its centennial, a Grand Exposition was held in Fairmount Park in Philadelphia. It celebrated the industrial march of progress from Alexander Graham Bell demonstrating the telephone to a massive 650-ton steam

engine built by Rhode Island’s George Corliss (standing seventy feet high, it was the largest engine ever constructed). At one point, Ulysses S. Grant and Frederick Douglass sat side by side onstage; a photograph of them together spoke volumes about the Union victory in the Civil War. The Grand Exposition, in fact, was the first world’s fair held in the United States, and more than 10 million people attended. Young Theodore was one of them. The Department of the Interior created a pioneering display showcasing America’s original native inhabitants in colorful ethnological detail. When Roosevelt visited the fair, what he marveled at most was the display of U.S. wildlife (assembled with help from the Smithsonian Institution), including a fifteen-foot walrus and an Alaskan polar bear. Huge aquarium tanks displayed the plethora of American fish, such as salmon and perch, an aspect of the exposition that Robert B. Roosevelt had been instrumental in creating.

18

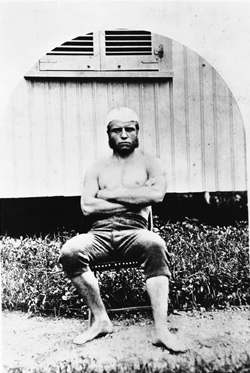

Roosevelt at Harvard University in 1877. Desperate to become masculine he worked-out everyday with free weights.

T.R. at Harvard. (

Courtesy of the Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard College Library

)

Also, 1876 was a presidential election year, with his father backing Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio and Uncle Rob behind Samuel J. Tilden of New York. T.R. didn’t get very involved even if, like all good young Republicans, he believed the campaign hoopla: “Hurrah for Hayes and Honest Ways!” Politics was thin gruel to Roosevelt. He complained that both Hayes and Tilden sneered at the teachings of naturalists such as Coues and Darwin. Roosevelt instead pored over zoology books, including the new

Manual of the Vertebrates of the Northern United States,

whose author, David Starr Jordan, was only seven years older than himself.

19

Suddenly, Roosevelt, influenced by Dr. Jordan and Uncle Rob, became interested in game fishes, particularly bass and trout; he was determined to enter Harvard as the best-rounded naturalist of his up-and-coming generation. As promised since the family trip down the Nile, Roosevelt was going to be a Harvard-trained foot soldier in the Darwinian revolution.

II

Before classes started in late September, Roosevelt tried to get his asthma under control. Unfortunately, his breathing had been thick for much of the year. It was as if a fungus had taken hold in his lungs. Because Harvard offered him only first-floor dormitory rooms, Roosevelt sought lodgings elsewhere. (Basements or ground-level rooms developed dampness and mildew, he claimed, which in turn triggered his coughing fits.) Roosevelt—already segregated from mainstream before the first day of class—rented a second floor suite in a house at 16 Winthrop Street (since torn down) just blocks from the campus. There were shady elm trees to admire from his four picture windows and, better yet, he could see the

Charles River from the rooftop. Worried that he’d turn his living quarters into a taxidermy studio, Roosevelt’s overprotective sister Bamie prepared the rooms, fixing up his study and alcove.

20

“Ever since I came here I have been wondering what I should have done if you had not fitted up my room for me,” he wrote to Bamie in earnest gratitude. “When I get my pictures and books, I do not think there will be a room in College more handsome.”

21

Within two or three weeks Roosevelt had transformed his Winthrop Street quarters into a virtual vivarium. Mounted birds cluttered his desk and a well-used portfolio of Audubon’s

Birds of America

was placed on his shelf like an old friend, soothing and familiar. Stuffed owls, deer antlers, bottles of formaldehyde, arsenic paste, wren’s nests, and colorful eggs abounded—and those were just the inanimate objects. Roosevelt was like a golden retriever; you never knew, when he entered 16 Winthrop Street, whether he would be carrying a wounded squirrel or a kicking rabbit. Then there were the live finches and tadpoles, mice litters, and a formicary. One evening, his landlady—a Mrs. Richardson—nearly tripped over one of his escaped turtles; her face turned white with fright. Even though Roosevelt’s rent money was good, the notion of having a philotherian tenant made her uneasy.

22

Having untamed animals running around indoors marked young Theodore as an eccentric at Harvard. This wasn’t necessarily a bad thing, since singularity had its time-honored virtues. After all, Cambridge was replete with brilliant characters. Oliver Wendell Holmes scouted the out-door bookstalls for rare editions, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow could be seen strolling down Brattle Street window-shopping for elegant canes. The great historian Francis Parkman was sometimes found in the library working on

Montcalm and Wolfe

, and Charles Francis Adams served as university “overseer.” Charles Darwin’s chief American supporter, the botanist Asa Gray, was no longer teaching at Harvard, but he lived near the campus and was available to answer questions about evolution if any student knocked on his front door. Ralph Waldo Emerson was spied from time to time poking around the campus. (His remark “Nature encourages no looseness, pardons no errors” always appealed to Roosevelt’s bare-knuckled Darwinian sensibility.

23

) Being different brooked no condensation at Harvard if you were intellectually astute.

24

While other freshmen were enthralled that William James and George Santayana were on the Harvard faculty, Roosevelt bemoaned the fact that professor Louis Agassiz—who, like Uncle Rob, had published a landmark book on Lake Superior—had died three years before. During the last year

of his life Agassiz—founder of Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, which soon rivaled its counterparts in London and Paris—traveled to Brazil as an ichthyologist, participated in a deep-sea dredging project sponsored by the U.S. Coast Survey, and founded the Anderson School of Natural History at Penikese Island off the southern coast of Massachusetts. “Study nature, not books” was Agassiz’s dictum. Clearly Roosevelt would have had a lot to learn from the charismatic zoologist, even though Agassiz had been an antievolutionist to the bitter end. One got the feeling Roosevelt had wanted to challenge Agassiz in class over the accuracy of

On the Origin of Species

. (The old-fashioned Agassiz had fought against having evolution as part of the museum.

25

)

Perhaps because Roosevelt was autodidact, he wasn’t inspired by any of the geology or zoology professors at Harvard. This attitude caused some classmates to consider Roosevelt a presumptuous snob, and it caused some of the faculty to write him off as lazy and pedantic. These professors weren’t pathfinders or explorers like Audubon or Darwin, and their lectures, without trailblazing deeds, did little to stir the imagination. Microscopes and laboratory garb didn’t interest Roosevelt in the least; the mastodon in Boylston Hall certainly did. A slightly above-average student, earning a cumulative seventy-five in his freshman year and an eighty-two as a sophomore, Roosevelt struggled most with foreign languages.

26

Nevertheless, he excelled in German, perhaps because he had lived with a German family in Dresden. Still, he extolled the virtues of Americanism every chance he could, and a slow-burning resentment toward European claims of intellectual superiority was detectable in his letters and diaries. He lampooned the smallness of England and the boorishness of Germany (although the primitive

Volk-moot

of the ancient German forests always interested him). Perhaps because they were predominately of Dutch ancestry, the Roosevelts often blamed Germany for the worst influences on American life. For example, in his novel

Five Acres Too Much

(1869), Robert B. Roosevelt complained that Staten Island was “overrun by sour-kraut-eating, lager-beer-drinking, and small-bird-shooting Germans, who trespass with Teutonic determination wherever their notions of sportsmanship or the influence of lager leads them.”

27

As for natural history, his major, Roosevelt’s excellence became legendary. However, the example of his faculty adviser, Professor Nathaniel Southgate Shaler, turned Roosevelt off even more from the idea of becoming a scientific naturalist. Ostensibly, Roosevelt should have liked Shaler, who was a prized student of Agassiz and who specialized in the

study of what were then called earth sciences. Serving as a captain in the Union Army during the Civil War, Shaler fought nobly; he returned to Harvard as a twenty-seven-year-old professor of zoology and geology in 1865 and would stay at Harvard the rest of his life. By the time Roosevelt arrived to take his Introduction to Geology course in 1876, Professor Shaler had made Harvard the center of American geological research, and his

The First Book of Geology

was considered a new classic in the field.

28

Training students in how to biologically observe natural selection was a specialty of Shaler’s; he was one of the first Americans to adopt Darwin’s specimen collection methods.

29

But for a young man who’d already shot plovers in the Middle East (as well as the Adirondacks), and was the son of a New York millionaire, Shaler’s explanations about shifting tectonic plates and paleontology seemed dull; the professor might be a young Turk, but he had abandoned nature’s awesome drama, Roosevelt believed, by an overreliance on arcane theories about ancient dirt and meteorite rock. It was naive of Roosevelt to think that naturalists were buckskin-clad outdoorsmen like Audubon or Wilson, spending their lives in the wild. To Roosevelt, Shaler was a pedant who talked about how the mechanisms of evolution still needed to be ironed out instead of hitting the trail on a treasure hunt. Roosevelt wanted to learn about types of skunks, not faux erudition from a self-conscious Kentuckian struggling to become a prig, poor man. Theodore challenged his professor regularly, until they squared off one afternoon. “Now look here, Roosevelt, let me talk,” an exasperated Shaler stated. “I’m running this course.”

30

Roosevelt whizzed his way through a slate of courses in the natural history department: Comparative Anatomy and Physiology of Vertebrates, Elementary Botany, Physical Geography and Meteorology, Geology, and Elementary and Advanced Zoology.

31

And in truth, even though Roosevelt refused to give him any credit, Shaler was an inspirational teacher, known for taking students on geology field trips in the tradition of his mentor, Agassiz. Roosevelt, in fact, went on an excursion with Professor Shaler to study glacially formed cliffs. Nevertheless, Roosevelt, in a swipe at Shaler, lamented that Harvard’s president, Charles Eliot, had failed to hire a first-rate “faunal naturalist, the outdoor naturalist, and observer of nature.”

32

Yet Eliot believed T.R. and Shaler were two peas-in-a-pod, regardless of intellectual differences.

33

Likewise, Roosevelt would convey to Gifford Pinchot that no matter what their squabbles had been, Shaler, in fact, was “a very dear friend of mine.”

34