The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (34 page)

Read The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America Online

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

Although North Dakota provided the “romance” of his life, it was also where his worries about the depletion of America’s natural resources took root. Nobody championed the conquering of the West by the U.S. Army, mountaineers, homesteaders, trappers, farmers, and ranchers more than Roosevelt. Already in 1887—as he worked on a biography of Gouverneur Morris, author of much of the Constitution and creator of the U.S. decimal coin system—Roosevelt planned on writing a multiple-volume work he called

The Winning of the West

, an epic history in the Parkman tradition

tracing American continental expansionism from Daniel Boone in 1774 to the death of Davy Crockett in 1836. Roosevelt even considered the genocide of Native Americans—which was indeed explored when the work first came out in 1894—as heroic. “The most ultimately righteous of all wars is a war with savages, though it is apt to be also the most terrible and inhuman,” he wrote. “The rude, fierce settler who drives the savage from the land lays all civilized mankind under a debt to him.”

84

Because Roosevelt had lived on the Dakota frontier, he felt ideally suited to write a paean to westward expansion. In many ways, he saw

The Winning of the West

as merely the logical next step following the publication of

Hunting Trips of a Ranchman

and

Thomas Hart Benton

. Even though the Allegheny upcountry of the 1770s was vastly different from the Badlands of the 1880s, Roosevelt found them deeply connected.

85

“We guarded our herds of branded cattle and shaggy horses, hunted bear, bison, elk, and deer, established civil government, and put down evil-doers, white and red, on the banks of the Little Missouri, and among the wooded, precipitous foot-hills of the Bighorn, exactly as did the pioneers who a hundred years previously built their log-cabins, beside the Kentucky or in the valleys of the Great Smokies,” Roosevelt wrote in the preface of Volume 1 of

The Winning of the West

. “The men who have shared in the fast-vanishing frontier life of the present feel a peculiar sympathy with the already long-vanished frontier of the past.”

86

Such triumphalist “white man’s burden” sentiments aside, Roosevelt nevertheless worried that the United States’ innate sense of opportunity had recently degenerated into exploitation. America knew how to conquer, but it was failing in the art of properly managing its hard-won resources. The West’s virgin woodlands were rapidly being logged and its rolling prairies plowed. Wetlands were being drained, and streams were being fished out. Everywhere Roosevelt went in the Dakota Territory, the topsoil had been leached of nutrients and signs of erosion were commonplace. It sickened him to see wild ungulates being poisoned and slaughtered because they supposedly ate the same grasses as cattle and sheep. Even the very wilderness of the West was disappearing in a maze of train tracks, barbed wire, telegraph lines, and meat-processing plants.

As Roosevelt surveyed the Dakota Territory in 1887, finding it nearly impossible to hunt a buffalo, elk, or pronghorn, he understood that the “winning of the West” had been accomplished at the expense of natural resource management, and it made him melancholy. Saving the American West from environmental ruin after the winter of 1886–1887 became a high priority for public policy. Even while he was counting cattle casual

ties from the “blue snow,” he was planning future western trips: to the Selkirks of British Columbia, the Bitterroots of Wyoming and Idaho, Yellowstone National Park, and the Two Ocean Pass of Wyoming. Each sojourn reinforced his newfound belief that the western terrain was a fragile ecosystem.

87

W

ILDLIFE

P

ROTECTION

B

USINESS

: B

OONE AND

C

ROCKETT

C

LUB

M

EETS THE

U.S. B

IOLOGICAL

S

URVEY

I

T

o offset his losses from the “blue snow,” Roosevelt wrote yet another book about his Badlands experiences, to be called

Ranch Life and the Hunting-Trail

, illustrated by Frederic Remington. (This book often gets mixed up with

Hunting Trips of a Ranchman

because, even though they were published three years apart, their titles are very similar.)

Ranch Life

would consist largely of articles Roosevelt had been commissioned to write for

Century

starting in late 1887, along with additional previously unpublished essays. An overarching conservationist message now emerged from Roosevelt’s hunting experiences: tragically, American big game was verging on extinction throughout the entire West. Consider how difficult it had been for Roosevelt to shoot a lone buffalo, or to find a grizzly bear. Poacher syndicates were even slaughtering elk within the confines of Yellowstone National Park. If law enforcement didn’t round up the illegal shooters and trappers, then doomsday, Roosevelt believed, lurked just around the corner for western wildlife.

The overwhelming question weighing on Roosevelt’s conscience as he worked on

Ranch Life

was simple: how could he be proactive to save big game animals? Although Roosevelt’s exact moment of reckoning remains unclear, in early December 1887 he found a conservationist solution to his quandary. Borrowing from the way his elders tackled societal ills, he would create a hunting club devoted to saving big game and its habitats. High-powered sportsmen like himself, he believed, banding together, had to lead a new wildlife protection movement. Posterity had a claim that couldn’t be ignored: saving American mammals was an imperative. A “fair chase” doctrine—hunting rules and regulations—had been created. And as far as Roosevelt was concerned, the time for watered-down measures had passed; his club would fight for true solutions, its goal being the creation of wilderness preserves all over the American West for buffalo, antelope, mountain goats, elk, and deer.

By the time Roosevelt left the Badlands for New York, his conservationist resolve had grown firm. What his Uncle Rob had done for fish, he would do for American big game. A day after arriving back in New York, in early December 1887, Roosevelt convened some of the best and brightest wildlife lovers and naturalists in the New York area to dine at his sister’s Madison Avenue home. He was ready to make a hard sell. If his father could found the American Museum of Natural History from a parlor in Manhattan, Theodore saw no reason why this group, meeting in the cramped uptown quarters he shared with Edith, Bamie, and little Alice when not at Sagamore Hill, couldn’t save buffalo and elk in the American West.

1

After all,

Hunting Trips of a Ranchman

had established him as

the

authority on big game. Roosevelt now had a sacred responsibility, he believed, to save herds of North American ungulates from extinction.

As his first step, Roosevelt asked George Bird Grinnell to be a co-founder of the Boone and Crockett Club (named after his two favorite, iconic trailblazers). Grinnell had already successfully created the Audubon Society and was editor of the respected periodical

Forest and Stream

, so he knew how to rally public opinion. Roosevelt always valued experienced help. Although Grinnell disdained lobbying, he was good at it. Grinnell fully approved of the project, and his willingness to join forces with Roosevelt to promote the conservation of big game animals and their habitat boded well for the eventual success of the Boone and Crockett Club. Roosevelt and Grinnell then lured a who’s who of other conservation-minded “American hunting riflemen” to serve as founders. All of the original twelve members, they insisted, had to espouse the “fair chase” philosophy and believe in the sanctity of national parks.

2

Roosevelt tapped his brother, Elliott, and his cousin J. West Roosevelt (both childhood veterans of board meetings for Theodore’s Roosevelt Museum during the 1870s) to join the Boone and Crockett Club. It was now the turn of their generation, emerging into maturity, to continue the kind of conservation work Robert B. Roosevelt had long championed. Most of the other founders were New York capitalists with deep pockets, like T.R. himself: E. P. Rogers, a yachtsman and financial investor; Archibald Rogers, the rear commodore of the New York Yacht Club; J. Coleman Drayton, who was John Jacob Astor’s son-in-law; Thomas Paton, the husband of the heiress Marion Rowle; and Rutherford Stuyvesant, a wealthy real estate investor. From the outset Roosevelt knew that large sums of money would be necessary to lobby effectively in Washington, D.C.

3

Basically, the founders were from the establishment, easily

distinguishable from the plain citizenry of New York even though none was afraid to get mud on his boots.

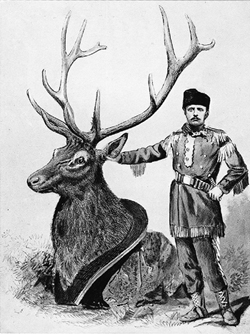

A drawing of Roosevelt standing next to a trophy worthy of the Boone and Crockett Club.

T.R. with Boone and Crockett Club antlers. (

Courtesy of the Boone and Crockett Club

)

In early January 1888, the twelve founders of the Boone and Crockett Club had approved a prescient conservationist constitution at Pinnards Restaurant in Manhattan. Ideas had been allowed to percolate freely. The thought of buffalo once again thundering on the plains aroused the founders’ enthusiasm during their inaugural deliberations. A decision was made from the outset that the club would have a permanent membership of exactly 100 hunters. The bylaws also stipulated that a limited number of associate members (no more than fifty) would also be allowed. Roosevelt—who would remain the club president until 1894—filled the associate memberships with a galaxy of truly talented writers, including Owen Wister and Henry Cabot Lodge (two outdoorsmen he admired unconditionally). Scientists, military officers, political leaders, explorers, and industrialists were also recruited as members, in hopes that they’d forge innovative solutions to stop the exploitation of America’s natural resources. Roosevelt himself brought in the army generals William T. Sherman and Philip H. Sheridan, the artist Albert Bierstadt, the former secretary of the interior (from 1877 to 1881) Carl Schurz, and the geologists Clarence King and Raphael Pulmelly.

4

“The members of the club, so far as it is developed, are all persons of high social standing,” an editorial

writer in Grinnell’s

Forest and Stream

said of the club’s founding, “and it would seem that an organization of this description, composed of men of intelligence and education might wield a great influence for good in matters relating to game protections.”

5

Among the Boone and Crockett Club’s original objectives, as stipulated in article 3 of its bylaws, were (1) to promote “manly sport with the rifle” (2) to promote “travel and exploration in the wild and unknown, or but partially known portions of the country” (3) to “work for the preservation of the large game of this country, and so far as possible to further legislation for that purpose, and to assist in enforcing the existing laws” (4) to “promote inquiry into and to record observations on the habits and natural history of various wild animals” and (5) to “bring about among the members interchange of opinion and ideas on hunting, travel and exploration.”

6

Bylaw 3 is the area where the club eventually succeeded beyond even Roosevelt’s wildest hopes.

The club’s members were indeed an aristocratic clique, pampered but not easily fatigued. Their first meetings were relaxed, as if the members were sitting around the lounge-library of the country manor hotel. Roosevelt served as a moderator, keeping the conversation on track, reminding the wildlife preservation gospelers to be pragmatic. In short order they came up with a set of reasonable rules, none more important than their own membership requirements. To be eligible, a hunter had to have successfully shot at least three varieties of North American big game with a rifle. Once inducted, members were sworn to maintain a strict code of honor—in particular, never lying about a kill and always behaving as serious naturalists. Frontier values, the founders agreed, built character and were to be encouraged. On a hunt, nobody was allowed to pull rank or claim privileges because of his social station—members were absolute equals when tramping. As a covenant all members had to be determined to save big game for future generations of Americans to enjoy. Although it wasn’t their main priority, club members all seemed to mourn the yearly loss of the “heritage” of American hunting.

Like membership in Skull and Bones or Porcellian, the very act of going on a hunting trip with a fellow club member created a lifelong bond of fellowship; after all, even Natty Bumppo seldom hiked in the Adirondacks or Green Mountains without Uncas or Chingachgook guides.

7

A general feeling among the members was that research on wildlife—habits, traits, coloration—could never be overdone. To all of the men, America without big game would be like an oak or sycamore tree that never had leaves:

totally unacceptable. By saving wild creatures, the Boone and Crockett Club was saving America’s outdoors heritage. Some members were given distinguished Native American names such as Pappago, Little Brave, and Running Waters.

8

On February 29, 1888, the founders drafted a constitution. The club has been described as the “first-ever organization to be formed with the explicit purpose of affecting national legislation on the environment.”

9

Its initial goal for wildlife conservation was to add enforcement provisions to the laws governing Yellowstone National Park. When Congress had established America’s first national park in 1872, it neglected to enact regulations punishing poachers, sawyers, vandals, or miners. As a result, many westerners treated the park as if it were ripe for plucking. Particularly, local wildlife was under siege from the Northern Pacific lobby (the so-called Railroad Gang) and its associated real estate speculators. If the park police happened on someone poaching or trying to haul out minerals, all they could do was escort the offenders to the boundary and expel them.

10

Therefore, the Boone and Crockett Club appointed a committee to “promote useful and proper legislation toward the enlargement of the Yellowstone National Park.”

11

As the railroad fought for a right-of-way through the park, and its allies pushed legislation reducing Yellowstone’s acreage, the Boone and Crockett committee lobbied for regulations with teeth in them.

12

There are about 130 boxes of largely uncataloged material at the club’s archives in Missoula that bear witness to how crucial Yellowstone preservation was to the founding members.

The club had real reasons to worry about wildlife depletion in the West. Audubon’s bighorn sheep, the eastern and Merriam’s elk, the heath hen, the Carolina parakeet, and the great auk had all gone extinct since the 1870s, to name just six examples. The once plentiful beaver was no longer found east of the Mississippi River. (Even encountering a beaver in the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains was a rare event by 1887.) The buffalo population had dwindled dramatically since the start of the century, from 40 million in 1800 to at most a couple of thousand in 1887. White-tailed deer were faring only slightly better: when Europeans first came to America, there had been approximately 24 million white-tailed deer, compared with just 500,000 at the time of the first Boone and Crockett dinner. Even wild turkeys—once nearly ubiquitous and numbering 15 million—were struggling, with current estimates of only 30,000. (Today the number is around 7 million.) “As sportsmen, the club founders were

very aware of what the plight of wildlife meant in terms of future hunting prospects,” George B. Ward and Richard E. McCabe explained in

Records of North American Big Game

. “As Americans, they saw clearly what it represented in broader resource terms to the national health. As businessmen, industrialists, journalists, and politicians, they recognized that it lay with them, and others of like vision, to attempt ‘so far as possible’ to relieve and correct the situation.”

13

The survival of two game animals Roosevelt had written about so authoritatively in

Hunting Trips

and in his outstanding articles for

Outing

—the pronghorn and elk—was a high priority of the Boone and Crockett club. Only 150,000 elk and 25,000 pronghorn remained in the West; each species was down 98 percent from counts early in the nineteenth century.

14

Yellowstone became the club’s special cause.

“So far from having this Park cut down it should be extended,” Roosevelt declared, “and legislation adopted which would enable the military authorities…to punish in the most rigorous way people who trespass against it.”

15

Many historians now believe that the Boone and Crockett Club—Roosevelt’s brainchild—was the first wildlife conservation group to lobby

effectively

on behalf of big game. The club sprinkled the issue of wildlife protection with kerosene, struck a match, and watched it take off. While antihunters sat on the sidelines gabbing about the extermination of the buffalo, Roosevelt and Grinnell popularized the sportsman’s code and called for protection of the buffalo in Yellowstone. In essence, the club became the most important lobbying group to promote

all

national parks in the late 1880s. Audubon’s six words—“surely this should not be permitted”—which Grinnell promulgated had now become the club’s rallying cry. And with the help of General Sheridan and Senator Vest, in particular, Roosevelt and his friends achieved very good press during their club’s first two years of existence.