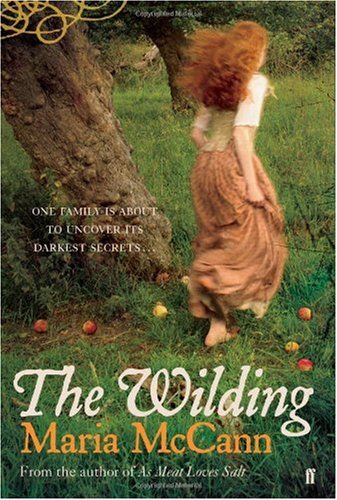

The Wilding

MARIA M

c

CANN

For SMH, who is both clever and wise

Title Page

Dedication

Note to the reader

1672

1: Of Apples in Eden

2: An Interlude

3: Of Mrs Harriet and her Household

4: Of Wandering

5: On the Natural Deceitfulness of Women

6: Of Murc and Rot

7: Of Home, and the Dreams I Had There

8: On the Desirability of Marrying Off Young Persons

9: Concerning That Broad Highway, The Road to Hell

10: After Fire, Ashes

11: None So Deep as a Dymond

12: Lovers of the Gentleman

13: The Kind of Man I Was

14: Man to Man

15: Attempts at Reasoning

16: The Wilding

17: Concerning Corruption in Cider

18: On the Disagreeableness of Home Truths

19: Of Diverse Sorts of Inheritances

20: How I Lost Part of My Hair

21: Settling Accounts

22: Advice to Live Happy

1674

23: Writings and Writings

Acknowledgements

About the Author

By the Same Author

Copyright

The incident in the Guild Hall at Tetton Green is loosely based upon events that occurred in 1645, when Royalist troops occupied the village of Doulting in Somerset.

1672

1

How well I remember it! There had been a village wedding that day. We had put the couple to bed and were bringing away our gloves and favours and cake; as we approached the house I saw the moon, huge and yellow, hanging over the roof as if to spy on us. Being tired and tipsy, I stumbled in the path and my father said, ‘Mind how you go.’ We were no sooner inside, and my mother gone to her chamber to take off her good gown, than there came a tapping at the door. Wondering who could want us at that time, and why the person had not spoken to us in the road, I opened it and found a little boy on the step.

‘Please, Sir,’ he said, ‘I’m to give this to Mr Dymond and nobody else.’

I now perceived something white in his hand. ‘Don’t you mean Mrs Dymond? It’s a childbed, is it?’

He shook his head. ‘Mr Mathew.’

‘I’m his son, you may give it me.’ I held out my hand, but the lad put his behind his back.

‘I won’t steal your letter,’ I said, laughing. ‘Come inside, before you fall asleep’ – for the little fellow was yawning and rubbing his eyes.

‘I did fall asleep, Sir, in the garden, Sir.’

‘You’ve come a long way, then?’

‘Please, Sir, from Tetton Green.’

A long way for a child in the chill autumn weather. I looked at him with new interest. ‘From my uncle – Mr Robin Dymond?’

Now it was his turn to look at me. ‘Is he your uncle, Sir?’

As we entered my father was standing at the hearth urging the fire into life. He had never caught the trick of building a fire and the flames had a flimsy, frivolous look. As he took the paper from the boy I seized the poker and raked the wood together until it roared, my father turning away in order to have its light on the letter. From where I stood I could see that it was but a few lines long, yet I had breathed in and out perhaps twenty times before he turned round. I saw his hand move as if to throw the thing into the hearth, and then draw back.

‘It’s too late for you to return alone,’ he told the boy, tucking up the paper into his coat pocket. ‘You shall stay the night here and return tomorrow.’

‘Sir, I was told not to. No matter how late, I’m to take you back with me. That’s what the man said.’

My father hesitated. The lad seemed to think he was being disbelieved, for he repeated, ‘He said that, Sir.’

During all this time Father had not looked at me. Now he said, ‘Jonathan, go and tell your mother what’s happened.&rsuo;

I said, ‘I don’t know what’s happened.’

‘My brother’s in a difficulty. I must see him.’

When I heard that

difficulty

, I knew I was not to be told the truth. My father was kindness itself and the word was his way of hedging round anything shameful: a drunkard who had fallen on his scythe and an unmarried girl with child were equally ‘in a difficulty’.

‘Then take Dunne’s horse,’ I said. I had already arranged to borrow the animal for my round the following morning; it was only a matter of begging a saddle.

‘No, no. It’s not so far to Tetton. Pray tell –’

‘It’s ten miles or more,’ my mother said, coming back into the room. ‘Who wants to go there?’

‘Robin has need of me.’ He handed her the letter. My mother is a slow reader who sometimes spells out words under her breath, but on this occasion she was watchful and let nothing slip. ‘Take the horse,’ she said. ‘Jonathan won’t mind, not this once.’

‘Indeed I won’t, Father.’

He shook his head. ‘I can walk. But give this lad a bed, I’ll go faster without him.’

When Mother saw that he was adamant, she took the boy into the kitchen where she gave him some hot ale. Then Father put on his hat (his coat, he had never taken off), kissed both of us and set out under the inquisitive moon.

* * *

Such messages as the boy had brought were usually for my mother. She was trusted by all and yet remained a kind of stranger in the village, having gone there with Father shortly after their wedding. Our home had belonged to Dymonds for generations, but not to our branch of the family; Father would never have inherited if not for the Civil War, which swept away a number of heirs and so handed the Spadboro house to us.

Before that time they lived in Tetton Green with Uncle Robin Dymond. Father had wished to install his younger brother in Spadboro along with us, but Uncle Robin stayed behind in his native village where he was about to make an advantageous match.

My mother, unlike Uncle Robin’s wife, was not a wealthy bride, but my parents did well enough. Though soft-spoken, they were active, hardy, contriving folk. In addition, they could both read and write, a great blessing; my father was even something of a scholar in his way, a lover of learning, and he brought me up to read and write likewise. They had married for love (though so, perhaps, had Uncle Robin) and there were never disputes about money or anything else in our house since my parents were agreed on the best way to live: the way of simplicity and honesty.

I have said my mother was not a wealthy bride. What she brought my father was more precious than mere cold coin: with some little help from our maid she did all the things that good wives do – ordered the household, made medicines and preserves, mended and cleaned our linen – and sometimes helput at births, especially those that were taking too long. This was what brought messengers at all hours of the day and night. As a boy I once asked her what she did on those mysterious occasions. She replied that her first task was to soothe the women, who were always afraid ‘because childbed is oft deathbed’ – a saying that made a lasting impression on me. Sometimes she stewed up herbs that helped the child to be born, or pressed on the woman’s belly to turn a baby coming out the wrong way. She witnessed agonies and wonders.

Those she ministered to must have respected her skill, for she was called upon more frequently as the years went by, until there was scarcely a married woman in the village who had not sent for her. And yet, despite bringing so many through their hour of need, she remained something of an outsider. My father was always that bit cleverer than his neighbours, and both my parents made corn dollies differently at harvest time: small things, to be sure, but small things loom large to country people.

Still, settle down they did, and I with them. All my childhood was passed in Spadboro; I grew up a proper village man, woven in. We had a bed of beans and cabbages and suchlike, a patch of corn, an apple orchard (with the odd pear tree) and a pig. There was plenty to do and I made myself useful, as boys must.

One task I relished above all others, so much indeed that it was not labour to me, but a pastime. This was the making of the cider. From October through to January I would hang around any farm or house where apples were ready. Alas, a child was of no use where the householder had a proper mill, except to help bring fruit to it. I much preferred houses where the crop was broken by hand, where some kind soul might pass me a stave so that I could stand alongside the other workers, fancying myself the best of any as we beat down the apples into murc. That done, I would whimper and whine to be allowed to help stack the murc and straw into a cheese for pressing. During those early years I was much too small for this task, and forever under the men’s feet, but they bore it good-humouredly. At last the cheese would be built and someone would hold me up to the press so that I could work the screw, or rather so that the man whose hand rested on the lever with mine could do so, I glowing with pride the while at my supposed strength.

There was always laughter and singing at cider-making time; I cannot recall any occasion when I was shooed away. Instead, the men would take turns at holding me up to the press so that I could try again; and when the first and sweetest must flowed from the cheese I was handed a barley-straw so that I could suck it up and pronounce it good.

*

My father soon noticed my love for cider-making, a love that did not diminish as I passed through boyhood and began to look and talk more like a man. Any boor can press apples, and some fathers might have felt shamed and tried to break me of such humble pleasures. Mine, however, believing that God implants a particular excellence in each man, and that only sin offends Him, tried to humour rather than thwart this strange propensity of mine. Having given thought to the matter, he set aside money each year (as my mother told me later) for when I was grown. In this way I came to have my press. He made me a gift of it on my twenty-first birthday, and told me that now I was of age, I was to run it for myself.

It was a thrilling, newfangled thing. Father ight=s full of projects, eager to improve anything that would bear improvement. Unknown to me, he had been months talking with the carpenter, fretting over its design.

‘You see?’ he said. ‘It comes apart. You can pack it up and take it about.’

Every other press I knew was a fixture, wedged tightly under the cider-house roof. This one could move, could travel; it was like no other device. I could scarcely wait for the next cider-aking when I would load up, hire Dunne’s horse and take myself off to the houses where they had apples but no press.

When I finally set out the following October my father’s judgement was proven sound. The screw was strongly made; our neighbours were pleased with the amount of must it forced from the fruit and I was asked to return. The cider-maker was always a welcome sight. Not everyone’s apples would be ready – some would need to sweat longer, the late varieties would not even be fallen – but those families whose fruit was ready, who were eager for the new cider and consequently fond of me, would help me load up the press, plying me with food and with news: who was married, who sick, who ruined, who with child, who grown rich, who dead since last I went that way. What with this, and the novelty of unfamiliar faces, I passed the time very pleasantly. But enjoyable though it all was, what I loved most of all was the making itself.

Certain smells seem old as Eden: heaps of apples on the turn, smoke coming off sweet wood, the earth opening up in spring. As long as there have been people, there have been these – so ancient they are, so God-given. I loved the heady stink of fermentation – ‘apples and a little rot’, as the cottagers said – and the bright brown sweat that dripped from the murc even before the screw was turned, the generous spirit of the apple that made the best cider of all. The villagers said ‘Good cider cures anything,’ and I agreed.

Once all the apples were milled and pressed the people would sometimes cut me a log by way of thanks, even though we had trees of our own, so that during my first two years we had several of these logs. My father complained that this was greedy and not the true custom, but my mother (who like me loved the scent of apple wood) quietened him and made him give in. All this happened in my first year with the press. I was twenty-six, and preparing for my fifth harvest, when my father was called away from home.

* * *

When I woke the following morning, it was a moment before I remembered Father was gone to Tetton Green. I opened the chamber shutters: the weather had turned mild and clear, excellent for travelling. His good fortune was mine also, for today I was to set off on my round.

My mother stayed with me as I ate breakfast, then came outside to see me off.

‘I’ll stay, if you wish,’ I told her as I harnessed Dunne’s horse. ‘Until we know what’s the matter with Uncle Robin.’

Smiling, she shook her head. I then asked after the boy, thinking I might question him and thus find out more, but Mother was again ahead of me; there was a glint in her eye as she replied, ‘You must get up earlier, son. He’s gone already.’

‘I’ll be back in a few days. The rest can wait.’

‘No need.’

‘I will, though.’

She kissed me and went to open the gate as I swung myself up behind the horse. The cart rattled out of our yard and onto the road. I waved to her, drew a deep breath of sweet crisp air and just touched Bully (that was the horse) with my whip. He bounded away and I felt myself come alive.

It was five miles or so to Medgeham. The village enjoyed a kind of local fame, for the girls there were exceedingly pretty, though it must be said they were vain with it. The loveliest came out of three families, all cousins: the Strakers, the Lacks and the Fannings. Mrs Straker, Mrs Lack and Mrs Fanning were sisters and once the cider harvest was in their husbands would hold a feast in the Strakers’ barn, and their daughters would dance. Then all the boys of the village would make up to them, and sigh, and hope they might find favour before the next cider-feast. It was high time the older girls found husbands, now, and since the last harvest some of them had done so; but they had married wealthier men from outside the village, leaving childhood sweethearts to sigh in vain.

With these cousins, I knew I stood no chance; but I did hope to marry within the next few years, both for my own sake and that of my mother, that she might have a daughter-in-law about her as she grew older. I could have married earlier, but nobody in the village suited me and my parents were too tender-hearted to arrange anything against my will, believing that I would come round to it in my own time. In this, their kindness perhaps outweighed their wisdom, but I saw no reason to despair. There were still willing girls enough; some, indeed, that would not have stayed for the wedding, but these I shunned, not through any extraordinary virtue – I was young, after all – but because my father was not a man to wink and talk of ‘sowing wild oats’. He had trained me up to conduct myself more honestly, and he meant me to keep to it.

I was there for the pressing, then, and nothing else. The Lacks had a press of their own, which they shared with the Strakers and the Fannings and with other villagers besides, but this year they had so many apples that they had sent to me asking the use of mine. I lent a hand at the milling, too, and in return the labourers helped me build up my ‘cheese’ in the usual way: a layer of barley straw, a layer of murc, more straw, more murc, over and over, the whole held in place by a wooden lift, until the press was piled high and thick. Then the finest must, that made the best cider, oozed forth of its own nature, without pressure. It was a dear sight to the men and women of the house. Charles, the youngest of the Lack boys, was brought forward to taste and pronounced it sweet, and then we began screwing down the press. The trickle swelled to a soft brown stream, and the labourers cheered.