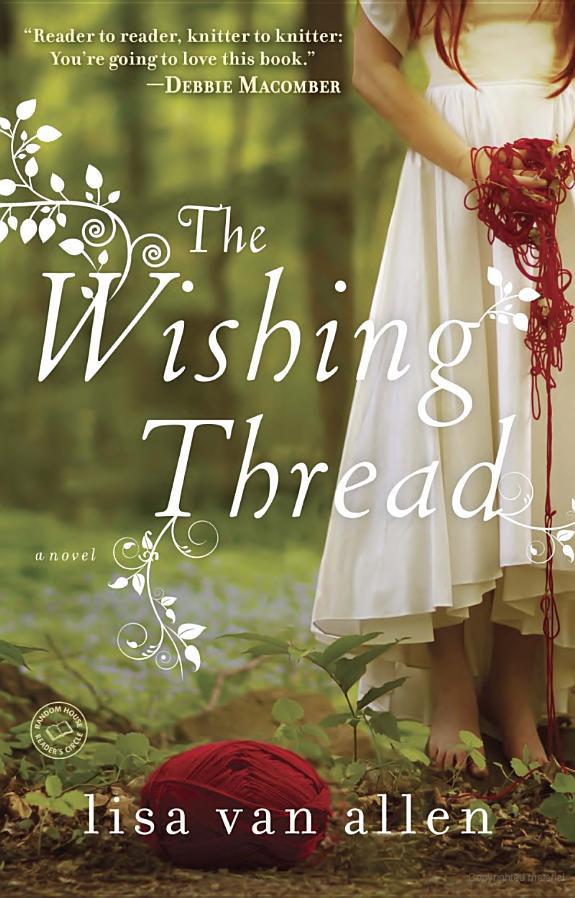

The Wishing Thread

The Wishing Thread

is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

A Ballantine Books Trade Paperback Original

Copyright © 2013 by Lisa Van Allen

Reading group guide copyright © 2013 by Random House, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

B

ALLANTINE

and the H

OUSE

colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

R

ANDOM

H

OUSE

R

EADER’S

C

IRCLE

& Design is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc.

Title-page art from original photographs by Beata Swi Chapter-opener art from istockphoto/Floortje

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Van Allen, Lisa.

The wishing thread : a novel / Lisa Van Allen.

pages cm

eISBN: 978-0-345-53782-9

1. Sisters—Fiction. 2. Tarrytown (N.Y.)—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3622.A5565W57 2013 813’.6—dc23 2013021730

www.randomhousehousereadershousecircle.com

Cover design: Laura Klynstra

Front cover photograph: © Patty Maher/Arcangel Images

Back cover photograph: © Goory/Shutterstock

v3.1

The humble knitter sits in the center between heaven and earth

.

—S

USAN

G

ORDON

L

YDON

,

The Knitting Sutra

I have read somewhat, heard and seen more, and dreamt more than all … I am always at a loss to know how much to believe of my own stories

.

—W

ASHINGTON

I

RVING WRITING AS

G

EOFFREY

C

RAYON

,

Tales of a Traveller

Mariah Van Ripper had never done things in life on anyone else’s time line, and dying had been no exception. On Mariah’s last earthly day in Tarrytown, her niece Aubrey had been sitting in the yarn room, the stitches of a lacy mohair shawl waltzing between her fingers. She hadn’t realized she’d been dozing, her mind wandering dreamy byways even while her fingers danced through stitch after stitch, until the moment that Mariah appeared in the doorway.

“Oh good. Aubrey! There was something I wanted to tell you.”

Aubrey looked up from her knitting. Framed by the doorjamb, Mariah listed slightly to the side like a wide flag waving in a gentle wind. She wore a long shapeless dress made of cotton so crisp and white that it nearly glowed.

“What are you doing back?” Aubrey asked. “I thought you had an appointment with Councilman Halpern. Did you forget something?”

“Yes … I believe I did.”

“Well, whatever it was, I would have brought it over to you if you’d called me,” Aubrey said, chastising a little. “What do you need?”

Mariah didn’t answer. Her eyes were wide and confused as a sleepy child’s. She murmured between half-closed lips.

“Mariah?” Aubrey stopped knitting at the end of a row, dropped her hands. The shawl lay sunlit and rumpled as yellow fall leaves in her lap. “What is it? What’s wrong?”

“Something I was going to tell you …”

“Well, let’s hear it.”

“Something …”

“Hey. You feeling okay?”

Aubrey watched her aunt’s pupils telescope into tiny black points. She seemed focused on something Aubrey couldn’t see, a speck of dust perhaps, dancing in the air, or some secret thought of her own, anchored so deep in her gray matter that her unseeing eyes drifted like boats from their moorings. Mariah was of middling height and impressive girth, with hair like long runny drippings of pigeon-gray paint. Although she had not been a beauty even in her youth, she had kind eyes, a generous smile, and deep, appealing wrinkles. The sun coming from behind her silvered her hair and the white hem of her dress.

“Ah, well,” Mariah said. “I guess you’ll have to figure it out.” She sighed, not unhappily. And then she stepped out of the yarn room and out of sight.

Aubrey set aside her knitting and crossed the wide wooden floorboards. She felt light-headed, caught up in the swill of her own worry. Mariah’s health had been in decline for the last few years, and it occurred to Aubrey that her aunt might be having a stroke. The doctors had warned them. Aubrey peered around the doorjamb; Mariah had vanished without the sound of a single footfall to mark the direction she’d gone.

Not even possible

, Aubrey thought.

But she called up the stairs anyway. “Mariah?”

She called down the hall. “Hey, Mari?”

She jumped when the phone rang. The hair at the nape of her neck stood on end.

She picked up the receiver very slowly. “Yes?”

“Aubrey Van Ripper?” a stranger asked.

It was then that Aubrey knew—knew before she’d been told—that her aunt had not returned to the Stitchery for some forgotten item. In fact, she was not in the Stitchery at all. And Aubrey thought of how vulgar it was that news of death, such an intimate and private thing, should be borne on the lips of a stranger.

For the first time in her life, Aubrey was alone, fully and finally and unexpectedly alone, alone in that moment and forevermore alone, her knitting needles stilled on a table in the yarn room, her ear hot from the press of the phone, and a stranger’s words floating to her from somewhere, not here, explaining a thing that had happened all the way across town.

In his private office not far from the Tarrytown village hall, safely ensconced behind neocolonial pillars and Flemish brickwork, Councilman Steve Halpern poured himself a drink from the small flask he kept for emergency use in his bottom desk drawer. The ambulance had left only moments ago, bearing Mariah Van Ripper’s body away from his office for the last time. He leaned back in his cigar-brown chair. It whined under his weight.

“You know, a person never

wants

to see a thing like this happen,” he said.

Jackie Halpern, who managed his electoral campaigns, his accounting, his sock drawer, and his blood-pressure medication, smiled. “Of course not.”

“But if it

had

to happen—”

“Don’t say it,” she told him. “I know.”

* * *

Slowly, like a thin vapor snaking its way inch by inch through Tarrytown’s friendly suburban streets, rumors of Mariah Van Ripper’s death spread among people who knew her and people who did not, until finally the fog of bad news wafted thick as raw wool down toward the river, down into the ramshackle neighborhood that Mariah had called home. The dogs of Tappan Square, mangy rottweilers and pit bulls that barked through closed windows, grew uniformly silent and did not so much as squeak at passersby. The oxidized old rooster atop the Stitchery’s tower spun counterclockwise in three full circles before coming to point unwaveringly east, and if any of Tappan Square’s residents had seen it, they would have known it was not a good sign.

Tappan Square was not Tarrytown’s best-kept secret. It did not factor into the region’s well-known, accepted lore. When visitors pointed their GPS systems toward Tarrytown and its sister, Sleepy Hollow, they always bypassed Tappan Square. Instead, they flocked to Sunnyside, the ivy-choked cottage where Washington Irving lived and died and dreamed of the Galloping Horseman and Ichabod Crane. They cowered happily at the foot of that tyrannical gothic castle, Lyndhurst, lording over the Hudson River with its crenellated scowl, and they pointed out landmarks from vampire horror movies in its dim, hieratic halls. They trudged among the lichen-flecked soul effigies at the Old Dutch Church, picking their way with cameras and sturdy shoes among tombstones that said

BEEKMAN, CARNEGIE, ROCKEFELLER

, and

SLOAT

. They searched for what everyone searches for on the shores of the Hudson River: enchantment. Some of that good old-fashioned magic. And yet, rarely did outsiders make their way to the neighborhood of Tappan Square, where salsa beats blared hard from the windows of rusting jalopies, where illegal cable wires were strung window-to-window, and where magic, or some

semblance of the thing, still found footing on the foundation of the building that the Van Ripper family had always called home.

The Stitchery, as it came to be called by neighbors and eventually by the family within it, had always been filled with Van Rippers. To its neighbors, the Stitchery was a curiosity like a whale’s eyeball in a formaldehyde mason jar, a taxider-mied baby horse with wax eyes coated in dust, a thing that should have been allowed to vanish after the life had passed out of it but instead was artificially preserved. With its architectural hodgepodge cobbled together over the centuries—its temperate Federalist core, its ardent mansard garret, its fish-scaled tower with witch’s hat roof—the house did not offer the most welcoming appearance. The latest batches of Van Rippers, most recently led by Mariah, did not believe in renovation. They did not repaint over the awful cabbage-rose wallpaper in the parlor, or fix the scrolling black gate in front of the house that had been knocked crooked during the Great Blizzard of 1888, or replace the sign on the front door that read YARNS even though it was nearly illegible with age. In fact, they vehemently protested such alterations and “unnecessary” upgrades as affronts to history. Mariah Van Ripper was said to have wept, actually wept, when one of the Stitchery’s great old toilets needed its innards gutted, and exact replacements for the old digestive system could not be found.

And so the Stitchery was allowed to fall out of fashion, then out of respectability, until it became a mote in an eyesore of a neighborhood, because Mariah had professed too much respect for her ancestors to fix a cockamamie shutter or tighten a baluster. This was the accretion of history that built up like dandruff or snow, and Mariah had always allowed it as one allows the sun to rise in the morning and set at night. Of course, her philosophy fit in nicely with her hatred of housework

and her unwillingness to spend what little money the Van Rippers made on such a frivolous thing as a new doorbell. But whatever the root motivation, the result was that the Stitchery—regarded by some as the heart of Tappan Square, and regarded by others as the tumor—was ugly, dilapidated, and falling down.