The Work and the Glory (123 page)

Note:

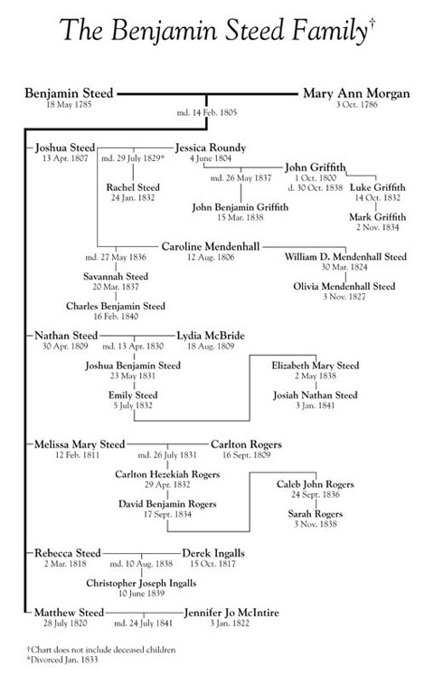

Melissa and Carlton (“Carl”) have two sons, but they do not figure prominently in the book.

The Smiths

* Joseph, Sr., the father.

* Lucy Mack, the mother.

* Hyrum, Joseph’s elder brother; almost six years older than Joseph.

* Jerusha Barden, Hyrum’s wife.

* Joseph, Jr., age thirty as the story opens.

* Emma Hale, Joseph’s wife; a year and a half older than Joseph.

* William Smith, a younger brother of Joseph’s; about five years younger than Joseph.

Note:

There are other Smith children, but they play no part in the novel.

Others

* Oliver Cowdery, an associate of Joseph Smith’s; one of the Three Witnesses to the Book of Mormon.

* Martin Harris, one of the Three Witnesses to the Book of Mormon.

Derek Ingalls, a factory worker in England; nearly nineteen.

Peter Ingalls, Derek’s younger brother; almost twelve.

* Heber C. Kimball, friend of Brigham Young’s and a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.

* Newel Knight, an early convert to the Church.

Caroline Mendenhall, a woman of Savannah, Georgia.

William Donovan Mendenhall, Caroline’s son; twelve.

Olivia Mendenhall, Caroline’s daughter; about three and a half years younger than William.

* Warren Parrish, an associate of Joseph Smith’s in Kirtland.

* Parley P. Pratt, an early convert and a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.

Clinton Roundy, Jessica’s father; saloon keeper in Independence.

* John Taylor, an Englishman residing in Toronto, Canada.

* David Whitmer, one of the Three Witnesses to the Book of Mormon.

Arthur Wilkinson, a young man from Kirtland, Ohio.

* Brigham Young, an early convert and a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.

Though too numerous to list here, there are many other actual people from the pages of history who are mentioned by name in the novel. Sidney Rigdon, Frederick G. Williams, John Boynton, Luke and Lyman Johnson, Isabelle Walton, Joseph and Mary Fielding, and many others mentioned in the book were real people who lived and participated in the events described in this work.

*Designates actual people from Church history.

Chapter One

Benjamin Steed was looking at his hands. He had them palms up, fingers bent over so he could examine his fingernails. He grunted softly in mild self-derision. These weren’t the hands of a dirt farmer. Not anymore. Five years in Kirtland had smoothed and softened them. They were callused—he still chopped his own wood, dug Mary Ann’s gardens, helped Nathan with the plowing now and then—but the hardness, the knotted muscles, the scabs and scars and blackened thumbnails were largely gone now.

He turned them over. For the first time he noticed an uneven brown spot on the back of his left hand. Absently he reached out and touched it with his fingertip. He also saw that the veins on the backs of his hands stood out more prominently now, like the furrows of a mole across a meadow. He hadn’t noticed that before either.

Like my father’s hands, before he died.

Surprisingly, the thought did not depress him. Next month Benjamin would celebrate his fifty-first birthday. It was no surprise that he was showing signs of aging.

A movement brought his head up. The Prophet Joseph was passing the sacramental bread to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, who were seated on the stand on one side of the western pulpits. Sidney Rigdon and Frederick G. Williams, his two counselors in the First Presidency, were assisting. Benjamin watched as the plates with bread passed among those on the front row—Thomas B. Marsh, David W. Patten, Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball.

The great room that occupied the main floor of the temple was filled to capacity. More than eight hundred Saints sat quietly and reverently, preparing themselves to receive the emblems of the Lord’s Supper. As the First Presidency finished passing the sacrament to the Apostles, the Twelve arose to help pass it to the congregation. It was the Sabbath in Kirtland, the first Sunday in April in the year of our Lord, one thousand eight hundred and thirty-six. It was a bright, sunny afternoon. Spring was heavy in the air and poured fresh, cool air through the great Gothic-arched windows.

Benjamin’s eyes dropped again to the spot on his hand.

Fifty-one years!

He marveled a little at the thought. He had been born in 1785, not even a full two years after the peace treaty was signed ending the revolutionary war. And now, here it was, more than a third of the way through the nineteenth century. That meant that, short of a miracle, two-thirds of his life was behind him. Possibly more. But he wasn’t bothered by that. He was, in fact, quite content.

He turned. Frederick G. Williams was at the end of their pew, extending the plate of broken bread to Mary Ann. His wife reverently selected a piece of bread and placed it in her mouth. Her eyes closed momentarily, then she took the plate, turned, and offered it to Benjamin, who quietly took a piece of bread and put it in his mouth.

He took the plate, then held it out for Rebecca, who sat on the other side of him. He watched her hands, graceful and elegant, as she took the bread. To the family, this youngest daughter had always been “Becca.” It suddenly occurred to Benjamin that of late he and Mary Ann had dropped the shorter form of the name and always called her by her full name. He smiled.

Rightly so

, he thought. At eighteen, she was fully a woman now—lovely, gentle, so much like her mother. So much like Isaac’s Rebekah of the Bible must have been.

He watched as the plate moved on, realizing that along this row sat the primary reasons for his contentment. Next to Rebecca were Nathan and Lydia. Not surprisingly, they were holding hands and had to disengage to take the bread. That took his mind back six years. Lydia had been the pampered, only daughter of one of Palmyra’s leading businessmen. Benjamin had been disgusted at the thought of his son marrying such a woman. “It ain’t smart to put a thoroughbred and a mule in the same harness,” he had grumbled. But he had been wrong. Dead wrong!

Beside Lydia sat Jessica Roundy Steed. Technically, Jessica was no longer related to the Steeds. Benjamin frowned. Thoughts of his oldest son still brought the same reaction—anger, frustration. Joshua had run away from Palmyra close to nine years earlier after a bitter confrontation between him and Benjamin. Then they learned he was married and living in Independence, Missouri. In the summer of 1831 Nathan had gone west with Brother Joseph to visit the land of Zion and look up his brother. What he found had rocked the family—a battered, pregnant wife and Joshua fled to Mexico Territory to escape the law.

By the time Nathan returned to Missouri with Zion’s Camp in the summer of 1834, Jessica had a two-year-old daughter and a divorce paper from Joshua. She had come back to Kirtland with Nathan, and she and Rachel now lived in a small cabin just next door to Benjamin and Mary Ann’s home. Here, as with Lydia, bonds had been forged now as strong as any blood ties.

The furrow in Benjamin’s brow smoothed as he let his eyes move to the last of the family members sitting on the row. Matthew Steed would be sixteen in July. The little towheaded, rooster-tailed boy who had incessantly tagged after his father was gone now. The blond hair was gone—it was dark brown now and thick as a tangle of prairie grass; the boyish slimness was gone; the high voice was gone now too, given way to the deep richness of a man’s voice. Matthew was a man now, straight and tall, full of fun and yet with a depth that was already causing older men to accept him with respect.

As he slipped the piece of bread into his mouth, he turned and saw his father watching him. There was a quick smile, like a flash of sunlight rippling off the waters of a pond.

Benjamin smiled back at him. He had learned, hadn’t he? He hadn’t repeated the mistakes he had made with Joshua. The relationship between him and Matthew had become a treasure of immeasurable worth.

The old Benjamin Steed had been all hard rock and thick logs. It had taken the Spirit a full six years to remodel the building into something more serviceable. But just a week ago, in this very room, during the temple dedicatory services, the Lord had whispered that he was pleased with the changes in Benjamin Steed. “Benjamin, my son,” had come the still, small voice, “be still and know that I am God. I am well pleased with your desires and with your labors.”

This was why today he could look at age spots on his hands, note the protruding veins, and still feel a great contentment. He reached out and took his wife’s hand. She looked up in surprise; then her mouth softened as she saw the love in his eyes. He gave her a gentle pull, bringing her shoulder up firmly against his.

“What?” she mouthed.

He shrugged, knowing he couldn’t tell her even if he wanted to.

* * *

“Hi.”

Every person sitting in the Steed parlor turned in surprise.

Melissa gave a little wave. She had come in through the back door, and obviously no one had heard her entry.

Her mother spoke first. “Did you forget something?”

She shook her head quickly, momentarily flustered by the small stir her return was causing. “No. I got young Carl and little David asleep.” She gave a little shrug. “Carl’s working at the stable. He said he wouldn’t mind if I came back and visited for a while.”

“Wonderful, Melissa.” Lydia slid closer to Nathan and patted the sofa next to her. “Come sit down. We’re all just sittin’ here being lazy.”

Removing her shawl and tossing it across the table in the hallway, Melissa moved over to take the place offered. “Have you got your three to sleep too?” she asked Lydia.

Lydia laughed. “I doubt it. Matthew took them home. Supposedly he’s getting them to bed, but . . .” She shook her head ruefully.

Benjamin sat in his favorite chair in the corner, a big wingback they had brought from Vermont to Palmyra, then to Kirtland. He shook his head. “You’ll be lucky if the house still sits square on its foundation when you get home. When he’s with them, Matthew is more kid than the grandkids.”

Melissa laughed, then looked around. “Where’s Jessica?”

“She and Rebecca are trying to get little Rachel to sleep,” Mary Ann said. “I think she’s coming down with something. Her head felt a little hot to me after dinner.”

Nathan leaned back on the sofa, stretching out his legs to their full length. He was pleased Melissa had been able to come back. Sunday dinner at Grandma and Grandpa’s house twice a month had become a family tradition. Following the afternoon worship services, they would all gather—sons, daughters, daughters-in-law, a son-in-law, and grandchildren. Fifteen of them in all. After a light supper, and after the dishes were done, they would gather in the parlor while the children played.

Melissa’s husband, Carlton Rogers—or Carl, as everyone called him—always came and seemed to enjoy it. He was not a member of the Church, and when he was with them the family made a special effort to avoid topics of religion or any discussion of people Carl did not know. He would join in the conversation, seeming relaxed and comfortable. But invariably he was the first to suggest it was time to go.

Nathan frowned slightly as he watched his sister throw back her head and laugh at something Lydia was saying. When Melissa and Carl had first begun to court, the Rogers family had been neutral toward the Church. Didn’t bother him none, Carl claimed, if Melissa was a Mormon. But in the last year or so Kirtland had seen a great influx of Latter-day Saints. Many came dirt-poor. It had thrown a burden on the community as well as the Church. Many of the locals had soured, blaming Joseph Smith and the Church for not doing more. Hezekiah Rogers, Carl’s father, had become particularly bitter, and that had undoubtedly influenced his son. In the last month or two, Carl had started to dig in his heels whenever Melissa tried to participate in Church activities. She had missed the temple dedicatory services the previous week, something which nearly broke her heart. But he wouldn’t budge. And today, being Easter Sunday, she had especially wanted to join the family at the worship services. He had insisted they attend church with his parents.

At that moment Melissa turned and caught Nathan’s eye. She smiled quickly. She and Nathan were only two years apart, and there had always been a deep bond of affection between them. It made him ache a little inside when he saw the hurt in her eyes and the eagerness with which she sought opportunities such as this tonight.

She reached across Lydia and touched Nathan’s arm. “Will you tell me about what happened in the temple today? I heard Mama and Lydia talking about it earlier.”

But just then, from behind them, someone spoke. “Wait for me if you’re going to talk about that.”

Everyone turned. Rebecca was standing in the hallway.

Mary Ann leaned forward to see Rebecca more clearly. “How’s Rachel?”

“Sleeping. I think she was just very tired. Jessica’s coming.”

“Good,” Melissa said, moving over closer to Lydia. “Come on, there’s room for one more here. I was just asking Nathan to tell me about today.”