The Work and the Glory (428 page)

“All right,” Markham yelled, grabbing the saddle horn and trying to pull himself up.

Three, four, five more times, Nathan felt the lancing pain. Twice they missed and hit the boot, but with such force that the leather was pierced and the flesh cut open. There was no alternative. His legs were on fire now and he could feel the blood trickling down into his boots. As he mounted his horse, out of the corner of his eye he saw Markham’s face, twisted in agony.

“Get out of here!” the sergeant yelled. Someone slapped the rump of Nathan’s horse and the animal leaped forward, almost throwing Nathan off. Grabbing the saddle horn, he managed to hang on as his horse pounded away. He looked back and saw that Markham was right behind him, also trying to hang on as his horse charged forward at a hard run.

They let the horses have their head until they reached the outskirts of the city. Then Nathan pulled up, breathing hard. Markham reined in beside him. “Are you all right?” Nathan gasped. He could see that all around the top of Markham’s boot was dark red. He looked down at his own legs and saw the dark stains.

“I’m all right,” Markham said, wincing even as he did so.

“What do we do now?” Nathan said, looking back toward the town.

“If we go back, they will kill us,” came the reply.

There was no disputing that. Getting back to Joseph and Hyrum was out of the question. Nathan thought quickly. “I say we ride for Nauvoo to get the governor. Either he sends help or we bring the Legion back with us.”

Markham hesitated for only a moment. “Yes,” he said. “We’ve got to get help.”

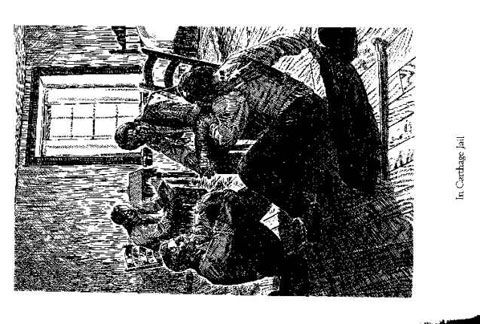

The Carthage Jail was started in 1839 and completed two years later at a cost of $4,105. Made of thick rock walls, the solidly built structure served as jail, debtor’s prison, and residence. Most of the main floor served as living quarters for the jailer and his family. There was a living room, a smaller dining room, and a kitchen. In the northwest corner of the main floor was the debtor’s cell, a cell used for those who were charged with lesser violations of the law, such as nonpayment of debts. Also on the main floor, attached to the outside of the building on the northeast corner, there was a frame addition that served as porch and “summer kitchen” for the jailer’s family. Just to the front of that was the well that furnished the jail with its water.

Upstairs, the entire back of the building was occupied by a long room with thick steel bars. This was called the dungeon, or the criminal’s cell. Here those charged with more serious crimes were kept. The rest of the second floor, except for the stairwell, was taken by the spacious bedroom that the jailer had offered to the prisoners. It had one window facing east and two on the south. These provided some movement of air if there was a breeze blowing.

By quarter to four on the afternoon of June twenty-seventh, there was no breeze and the upper room was a sweatbox. All three windows were open but it made little difference. Joseph and Hyrum Smith and Willard Richards and John Taylor had all removed their coats and were in shirtsleeves. They said little now. Their mood was one of growing melancholy. Governor Ford was gone. Nathan and Markham had left almost two hours before and had not returned, which was an ominous sign. Outside, the Carthage Greys were becoming increasingly raucous and irritable. Through the open windows came a constant stream of profanity, filthy stories, and endless bragging about what they planned to do with old Joe Smith now that the governor was gone. Tempers were short. Someone made an insulting comment and in an instant they were at each other’s throats.

Suddenly John Taylor could bear no more. He sat up and began to sing in a low, sorrowful voice.

A poor wayfaring man of grief

Had often crossed me on my way,

Who sued so humbly for relief

That I could never answer, Nay.

The others turned in surprise, then sat up to listen. John Taylor had a rich tenor voice, and his British accent made it seem all the more full and resonant.

I had not power to ask his name;

Whither he went or whence he came;

Yet there was something in his eye

That won my love, I knew not why.

The melody was somber and thoughtful, a perfect choice for the mood that filled the room. The words told the story of a stranger who appeared again and again, and always in desperate need of help—he was without food, he was near death with thirst, he was caught in a howling storm, he was found beaten and wounded by the wayside. And again and again, the words told of reaching out, usually with great sacrifice, to help meet the stranger’s needs.

Joseph was transfixed, watching Elder Taylor with wide, impassive eyes. Hyrum sat with his head down on his arms. Willard Richards’s head was tipped back, his eyes closed. It was as though Brother Taylor’s voice had pushed back the obscene sounds of the outside and now filled the room with a quiet reverence.

In pris’n I saw him next—condemned

To meet a traitor’s doom at morn;

The tide of lying tongues I stemmed,

And honored him ’mid shame and scorn.

My friendship’s utmost zeal to try,

He asked, if I for him would die;

The flesh was weak, my blood ran chill,

But the free spirit cried, “I will!”

At the mention of prison, Brother Taylor’s voice faltered momentarily, but he pushed on. Now Hyrum’s head was up. Willard Richards opened his eyes. Each one watched John Taylor. Coming to the seventh and final verse, he sang now with sudden joy.

Then in a moment to my view,

The stranger started from disguise:

The tokens in his hands I knew,

The Savior stood before mine eyes.

He spake—and my poor name he named—

“Of me thou hast not been asham’d;

These deeds shall thy memorial be;

Fear not, thou didst them unto me.”

The last note ended and hung in the air. If there were sounds coming from the mob outside, they did not hear them. The song had transformed them. Finally, Hyrum stirred. “Thank you, Brother John. I love that song. Will you sing it again for us?”

Elder Taylor seemed almost surprised that there were others in the room with him again. He looked at each of them, then shook his head. “Oh, Brother Hyrum, I do not feel like singing.”

Hyrum leaned forward. “Never mind, John. Commence singing again and you will get the spirit of it.”

For a long moment, the Apostle stared at the others; then finally he nodded and began again.

It was about two miles west of Carthage. There were four or five dozen men milling around. Horses were tethered to a thick patch of brush off to one side. Again and again single riders, or groups of two or three together, would come cantering up to join the others. They were welcomed with loud calls and bursts of laughter. Several jugs of whiskey, most nearly empty now, were passing here and there among them.

As four o’clock approached, suddenly someone shouted. They all turned. The man was pointing to the west, down the Carthage-Warsaw Road. A cheer went up and down the line. Coming toward them in a ragged line was a body of horsemen. The Warsaw boys were coming, and Thomas Sharp, editor of the

Warsaw Signal,

was riding at their head.

As they rode up—there were about as many newcomers as there were those waiting for them—they were welcomed enthusiastically, with backslapping and handshaking and passing of the jug. Finally, the leader of the waiting group raised his hands and shouted for silence. “Men,” he cried, “the hour has arrived.”

A shout went up and he let it roll for a moment, then raised his hands again. The men instantly quieted. “As you know, Joe Smith and his brother are seeking a solution to this problem in the courts.” An angry muttering rose from the group.

Thomas Sharp swore, then lifted his rifle high above his head and shook it at the sky. “The only courtroom that matters today is powder and ball.”

There was a triumphant roar.

The first man smiled thinly, waiting for it to quiet again. Then he turned to Sharp, pointing to where several buckets were lined up in a row. “Some of our men are a little nervous about being identified. We’ve mixed up some buckets of mud and gunpowder.” He turned to face the crowd around him. “If any of you are of a mind to, here is something to blacken your faces. If you want to ride in as you are, so be it. We leave in half an hour.”

Hyrum was seated at the table reading quietly from

Antiquities of the Jews

by Flavius Josephus. Joseph was sitting in the chair opposite him, listening without comment. John Taylor was stretched out on the bed. Willard Richards stood at the window that looked out to the east. Suddenly, he cocked his head, listening. “Do you notice anything?” he asked. They all turned to look at him.

“Like what?” Hyrum asked.

Elder Richards moved away from that window and started toward the two windows that were on the south wall. “Like how much quieter it is now.”

Hyrum set the book down. Joseph turned in his chair. “Yes,” Joseph said. “It

is

quieter all of a sudden.”

The Apostle moved to the window that looked almost straight down on the entrance to the jail. He pulled the curtain back a little so he could see out. There was a soft grunt of surprise.

“What?” Elder Taylor asked, sitting up now.

“They’re gone.”

Joseph stood and moved toward him. “Who’s gone?”

“The guards. All but”—he counted quickly—“eight.”

Joseph came to stand beside him, looking down at the men who stood or sat near the front entrance to the jail. He too counted, then shrugged. Before, there had been enough to completely encircle the jail. Now there couldn’t be enough to even adequately cover the front entrance.

Brother Taylor lay back down again. “They changed the guard yesterday about this time too.” He checked his watch. “Yes, it’s four o’clock.”

Elder Richards nodded, accepting that, but he stood there, looking down on the greatly diminished numbers. Finally, he too moved away, feeling vaguely uneasy.

There were several thousand people gathered in the streets around the Mansion House. Governor Ford, immediately upon arriving in Nauvoo, had asked the city leaders to call the Saints together. In a city already gripped by fear, the word spread rapidly. Like most of the population, the Steeds had dropped whatever it was they were doing and flocked to learn what was happening. Now Ford stood atop the partially completed building that Joseph had used to address the Legion a week before.

They stood in gloomy silence as Ford imperiously harangued them. There was no conciliatory gesture toward the Saints here, not even an attempt to find some middle ground for a solution. He spoke as though every man, woman, and child in Nauvoo had shared in the act of riot. It was condescending, insulting, demeaning. They should be praying Saints, he said, not military Saints. If they sought to retaliate in any way against those who were bringing their leaders to justice, every man, woman, and child in Nauvoo would be exterminated, he promised. The Saints didn’t like it, and a low undertone of angry muttering could be heard throughout the large audience.

Joshua stepped closer to Benjamin. “This is not good, Pa. Why is he here and not in Carthage where his presence is needed?”

Benjamin shook his head. “The city council was told that the people of Carthage are afraid we’re going to call out the Legion and send them to free Joseph. He’s supposedly here to see that doesn’t happen.”

“My fear,” Derek growled, “is that they’re

not

going to call them out.”

Joshua started to respond to that when a movement caught his eye. Porter Rockwell was near the edge of the crowd motioning frantically for him to come. Joshua pointed at himself, with a questioning look, and Rockwell vigorously nodded. Joshua slipped through the crowds to where he stood.

“What’s the matter?” Joshua asked.

“Something’s afoot here,” Porter said in a low voice, “and I don’t like it.”

“What do you mean by that?”

Rockwell lowered his voice, looking around. “Well, right now, for example. Are you catching the gist of his message? He’s warning us against any retaliating. For what? Nothing’s happened yet. Joseph and Hyrum are still awaiting trial, and yet he speaks as if something has already taken place.”

Joshua turned to stare suspiciously up at the man who was the governor of their state. There was an element of that in his words.

“There’s more. As you know, the governor and his staff went to the Mansion House when they first arrived here to rest and refresh themselves.”

“Yes.”

“Well, as I was about to come over here, I realized I had left my hat in the room where they were staying. I was just going to slip in and get it and then slip right out again. But when I walked in, a man was standing by the governor. This man was the only person speaking. He had one hand raised high. Just as I opened the door, he dropped his arm, like he was chopping something off. And as he dropped his hand he said, ‘By now, the deed should be done.’”