The Work and the Glory (579 page)

Key to Abbreviations Used in Chapter Notes

Throughout the chapter notes, abbreviated references are given. The following key gives the full bibliographic data for those references.

CHMB

Daniel Tyler,

A Concise History of the Mormon Battalion in the Mexican War, 1846–1847

(1881; reprint, Glorieta, N.Mex.: Rio Grande Press 1969.)

Chronicles

Frank Mullen Jr.,

The Donner Party Chronicles: A Day-by-Day Account of a Doomed Wagon Train, 1846–1847

(Reno: Nevada Humanities Committee, 1997.)

CS

Richard O. Cowan and William E. Homer,

California Saints: A 150-Year Legacy in the Golden State

(Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1996.)

MB

Norma Baldwin Ricketts,

The Mormon Battalion: U.S. Army of the West, 1846–1848

(Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press, 1996.)

MHBY

Elden J. Watson, ed.,

Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 1846–1847

(Salt Lake City: Elden J. Watson, 1971.)

OBH

George R. Stewart,

Ordeal by Hunger: The Story of the Donner Party

(Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1988.)

Overland in 1846

Dale Morgan, ed.,

Overland in 1846: Diaries and Letters of the California-Oregon Trail

(1963; reprint, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993.)

“Pioneer John Zimmerman Brown, ed., “Pioneer Jour-

Journeys” neys: From Nauvoo, Illinois, to Pueblo, Colorado, in 1846, and Over the Plains in 1847; Extracts from the Private Journal of the Late Pioneer John Brown. . . . ,”

Improvement Era

13 (July 1910): 802-10.

SW

David R. Crockett,

Saints in the Wilderness: A Day-by-Day Pioneer Experience,

vol. 2 of LDS-Gems Pioneer Trek Series (Tucson, Arizona: LDS-Gems Press, 1997.)

UE

Kristin Johnson, ed.,

“Unfortunate Emigrants”: Narratives of the Donner Party

(Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press, 1996.)

“Voyage” Lorin K. Hansen, “Voyage of the Brooklyn,”

Dialogue

21 (Fall 1988): 47-72.

WFFB

J. Roderic Korns, comp.,

West from Fort Bridger: The Pioneering of Immigrant Trails Across Utah, 1846–1850,

ed. J. Roderic Korns and Dale Morgan; revised and updated by Will Bagley and Harold Schindler (Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press, 1994.)

What I Saw

Edwin Bryant,

What I Saw in California

(1848; reprint, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1985.)

All Is Well

Why should we mourn or think our lot is hard?

’Tis not so; all is right.

Why should we think to earn a great reward

If we now shun the fight?

Gird up your loins; fresh courage take.

Our God will never us forsake;

And soon we’ll have this tale to tell—

All is well! All is well!

We’ll find the place which God for us prepared,

Far away in the West,

Where none shall come to hurt or make afraid;

There the Saints will be blessed.

We’ll make the air with music ring,

Shout praises to our God and King;

Above the rest these words we’ll tell—

All is well! All is well!

—William Clayton

Chapter 1

Are you still awake?”

Joshua spoke in a low murmur. Caroline had stirred a moment before, but he wasn’t sure if she was, like him, lying there in the darkness far from sleep. But there was no answer, and as he listened carefully he could hear her breathing softly but deeply. His mouth softened and he turned his head toward her, resisting the temptation to reach out and gently caress her face. He could see nothing, not even the outline of her, but he was sure that if suddenly a light were to illuminate the inside of the tent, Caroline Mendenhall Steed would be smiling softly in her sleep. And rightly so. She had waited a long time for what had happened this day.

He grinned in the darkness as he remembered Brigham Young’s words to the people who had gathered to witness Joshua’s baptism. “A giant in the forest has fallen.” And then there was Brigham’s droll smile. “And he has fallen right into our hands.”

He closed his eyes.

O God. How did you ever see fit to take mercy on one whose heart was so hardened? What ever possessed thee to reach out and save me from my own blindness?

The answer was simple. How many times had Caroline prayed in his behalf? How many tears had she shed? But then, he thought, it went back further than that. Joseph and Hyrum Smith had first come to the Steed farm back in New York in the spring of 1827. Within a year, Nathan and Mary Ann were convinced that Joseph’s fantastic account of the Father and the Son appearing to him in a grove of trees and of angels and golden plates was true, and Joshua had bitterly turned against it. How many times had his mother been on her knees?

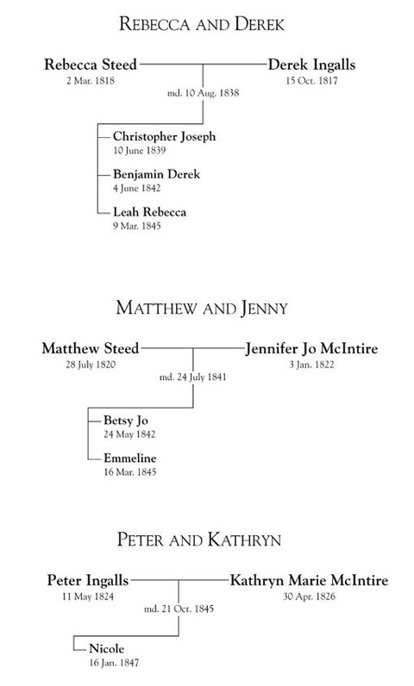

He was staggered now by the sheer number of prayers that must surely have been offered in his behalf. Will. Alice. Sweet and stubborn Savannah. Derek and Rebecca. Matthew and Jenny. His father. He turned away, eyes burning. And Olivia. This was the greatest pain for him. Even now it was as fresh and excruciating as when he learned that there had been an accident and Olivia had been killed.

Oh, Father, I would give my all

—there was a sudden, fleeting smile as he realized that at the moment that wasn’t much of an offer—

I would give everything if I could walk those paths again. If I could rectify some of the pain and the hurt and the loss.

His thoughts came back to Caroline. He had caused a lot of suffering for many people over the last twenty years, but Caroline had endured the most. His mind turned to those who didn’t know yet. Oh, how he longed to be present when they first learned the news that Joshua Steed was now a member of the Church! Jessica and Solomon back at Garden Grove, Peter and Kathryn somewhere out on the trail ahead of them,

Carl and Melissa.

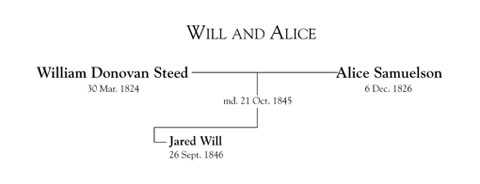

That thought stopped him for a moment. He would have to send a letter back to Nauvoo with the news. Carl would be stunned. Joshua had been his one ally in the family, the one other holdout against their beliefs. Now Carl was alone.

Joshua sighed. Most of all he wanted to share his news with Will. Where were he and Alice by now? He thought of the vastness of their sea voyage and felt a little sick. Had there been any problems? Was Alice with child yet? Had they reached Upper California? How long before they would see them again? It was a terrible frustration knowing that he couldn’t even send them a letter. But then he shook his head. No, this news could not come by letter. Not for Will. That had to be face to face, no matter how long it took before they were reunited.

And with that, he slid closer to his wife, gently putting one arm around her and pulling in closer. She stirred, snuggling in against him. She half turned her head. “You still awake?” she mumbled.

He grinned. “No.”

“That’s good.” It was a faraway murmur.

He pressed his face against the back of her head. “I love you, Caroline Steed,” he whispered.

“Hmm.” And she was gone again.

He smiled, knowing that she would remember none of this in the morning. But it was all right. He closed his eyes and lay back. Tonight, everything was all right.

When they were stretched out in one great line—as they were today—the Russell wagon train, with its forty-plus wagons, covered almost a full mile of trail. If you added the large herd of oxen and cattle that trailed behind, it was closer to a mile and a half from lead scouts to last cow. Not that Kathryn Ingalls could tell any of that from sight alone. Through the great curtains of dust which veiled the train she was fortunate if she could see more than two wagons ahead.

Summer had finally come. The pleasant spring temperatures were gone, and the earth was battered relentlessly by a sun that shone out of a cloudless sky. What had once been mud was now brick-hard soil, so that those riding aboard the wagons were jolted and jarred with numbing consistency. By an almost constant repetition of wagon wheels that had passed over the ground, the hardpan was chewed into a fine powder that lay ankle deep and exploded upward with the slightest provocation.

When the terrain allowed it, the company would spread out across the prairie horizontally, each wagon or small group of wagons choosing its own way so as to stay out of the endless dust of those before them. Often, however, the trail narrowed to a single track and the dust became unbearable.

Kathryn Ingalls had an especially difficult time. She, like everyone else, buttoned her collars and sleeves as tightly as possible. She wore a bonnet over her hair and a scarf across her face. That alone was enough to make the heat almost intolerable. But she had no choice except to ride in the wagon. Others could get out and walk and escape the worst of the dust. Kathryn could not. Though she could tell that the exercise she was getting was strengthening her legs, there was no possibility of her walking alongside the wagons.

She had heard stories that the Indians out here complained that the white people carried an unbearable odor about them. At first Kathryn had dismissed that as another of the unending rumors that made their way up and down the trail. Now she no longer doubted it. If the only whites the natives ever met were those traversing the trail, it was no wonder they complained. She tried to wash off as best she could each night. But privacy was limited, and she could do no more than use a cloth. Occasionally they would stop long enough to cordon off a place of privacy along the river and let the women bathe and wash their clothing. But that was rare. It was mid-June already, and they still had a thousand miles to go. Colonel Russell was not of a mind to spend a lot of time on making women comfortable.

She did have to admit that Russell’s determination was paying off. Though it seemed as if they were barely crawling, they were three hundred miles west of Independence and making twenty or sometimes twenty-five miles per day. The people were toughened up now, and so were the teams. Kathryn marveled when Peter removed his boots and socks and she saw the bottoms of his feet. The calluses were half an inch thick and almost as tough as the leather soles of his boots. She too had toughened. She knew that, and it gave her pride. If she could just relieve the endless misery of the dust and heat . . .

Not that the Platte was a great place to bathe. It was a broad, shallow river that meandered sluggishly eastward across the nearly flat plains. Its waters were heavily silted and ran a chocolate to a reddish brown color. Unlike the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers, which inspired such names as “the Wide Missouri,” “the Father of Waters,” and “the Mighty Mississippi,” the Platte brought forth a host of more whimsical quips. “It’s a mile wide and an inch deep.” “It’s too thick to drink and too thin to plow.” “It’s the only water you have to chew.” But right now Kathryn would gladly take an opportunity to bathe, no matter what the river was like.