The World is a Carpet (19 page)

Read The World is a Carpet Online

Authors: Anna Badkhen

Six months earlier, in Toqai, Taliban gunmen had opened fire during a wedding because there had been live music and dancing. Now musicians avoided traveling to weddings in villages they did not know well, whose security they could not vouch for. No one came to strum the twangy goat-gut strings of a

rubab

at the wedding of Naim and Ozyr Khul to Mastura and Anamingli. No one came to amuse their guests with the alternating lonesome wails and shrill cheer of the apricot-wood

tuiduk

, the flute Archangel Gabriel once had used to breathe soul into the clay body of Adam.

“No one wants to come here,” the Commander said. To underline the severity of his proclamation, he fished a harsh Korean cigarette from the chest pocket of his vest, stuck it between his teeth, and lit a match to it. He had started smoking cigarettes again. His abstinence from tobacco had lasted five days. He counted them out on his chapped fingers and held up the fingers to the diaphanous Khorasan sky as if calling upon the sky’s witness. Five.

And so it fell to the women to make music that wedding day. Modesty and custom demanded that the women party separately from the men, and to protect their dignity, no cell phones were allowed in Oqa during the wedding. It had become common for Afghan men to record videos of wedding dances on their cell phones and send them to one another by text, but some people considered such videos indecent. Several years earlier in Toqai, relatives of a bride shot to death two male guests for videotaping the wedding party. In Kabul, wedding photographers were receiving death threats.

The women had staked out the south-facing bank of the hummock that sloped down from the homes of Baba Nazar and Choreh and the new house of Ozyr Khul and Anamingli, and had strung some blankets and bedsheets between the adobes to fence off themselves from the ogling of the men. Within that provisional enclosure, they were in constant motion. Like a cageful of restless firebirds. They had dialed up the volume on Baba Nazar’s radio to the maximum setting and clapped their hands and ululated and sang and laughed and banged out a syncopated, urgent rhythm on goatskin tambourines called

doyra

. They held the tambourines over their heads and in front of their sequined breasts and at their glittering hips, and turned in an undulating circle, tossing their bare heads and letting their unbraided hair cascade like mountain rivers unimagined in this desert, each girl and woman an explosion of all the dreams and all the stars that would draw across the sky that night. Hot wind whirled their music through the village and past the ears of the men and out into the dunes, which had fallen silent in the face of such extravagant reverie.

• • •

The men were swatting at wasps and picking at deep-fried pancakes of slightly sweet dough shaped like shoe soles and nodding their heads to the beat of the women’s

doyra

when a group of dusty children led by Hazar Gul, Choreh’s daughter, stormed into their midst and prodded Ozyr Khul forward. He was deep red in the face and very small in his fuchsia skullcap.

Busted.

Three older men rose from their mats and stood above him. Like guardians or vultures or maybe a little bit of both. Each two heads taller than the boy. The men held him gently by the shoulders, and one of them took from his sweaty hand his only prized possession: the slingshot with which he and the boys had competed with such fervor over who could hit more accurately the spot on an electric pole where it should have been connected to something but wasn’t.

Then they wheeled him around and led him into one of the houses where his portion of wedding pilau was waiting for him. Sticky opalescent rice to seal his fate. A fate not so different from the fate of most men in Oqa, scripted by centuries of life and war in the desert: he would draw murky water by rope out of an open well seventy-five feet deep. He would never have enough to eat, and his teenage wife would grow old by her second child. God willing, the children would live past the age of five. His wife would weave carpets and support his family. He would smoke opium to take his mind off his tribulations. He never would learn to read and write. His honeymoon would last three days, and then Ozyr Khul would return to collecting calligonum thorns under agonizing sun to barter in Zadyan or Khairabad or Karaghuzhlah for oil and rice and wheat.

“The boy is very young,” said Amanullah. “He won’t know what to do with the bride. He may just end up smelling her, that’s all.”

“Nowadays, they grow up so quickly,” replied Janni the warlord. “I’m sure he knows everything there’s to know already.”

And that was the last time anyone ever would make any jokes about Ozyr Khul’s age or male prowess. After all, the whole village and the whole desert and really the whole world were complicit in his marriage. It was they who had decided that it was time for the boy to become a man.

The forward-moving rhythm of the women’s songs egged the sun up, up, up into the sky, and on, on, on across the flat world until the wedding day turned into the wedding night. Across the tiny and at once immense world where Ozyr Khul now was the head of a household and Naim at last was no longer a bachelor. Then a fast and technicolor sunset flashed over the village, and it was dark, and the epicanthic moon rose out of the eastern haze to blot out the Big Dipper star by star.

A

few days after the wedding, after most of the guests had gone back to their own villages and towns and the west wind had caked with a film of fine golden moon dust the large home-stitched triangular amulets that hung above the doors of the two newlywed couples to protect their marriages from the evil eye, Thawra returned to her loom room with a chipped glass cup of hot green tea in one hand and the green thermos with three fading tulips in the other.

She leaned over the loom and set the cup in an alcove next to a pair of her husband’s black rubber shoes shaped like sneakers and turned the cup so that its handle faced the room. She placed the thermos on the floor. She straightened up and, as she did each time before setting to work, adjusted her headscarf where it tied at the nape. She shook off her rubber flip-flops—

thwack, thwack

—and stepped in bare feet upon the foot-long section of the rug she had already woven. The tight and springy pile of the world’s most beautiful carpet pushed against the callus of her indigent soles.

The woman squatted facing north. She glanced at the unfinished design of her handiwork, the flowers unbloomed, the lines uncrossed. Then she picked up the end of an indigo thread and ran it around two warps and pulled on it and cut it off with a sickle.

Thk

.

In the bedroom across the hallway, Baba Nazar, Amanullah, and Nurullah slouched together on a mattress, half asleep. On the

namad

in front of them stood the old transistor radio that had blared Turkoman songs during the first wedding in Oqa in a decade. Now it was crackling war news. In the province of Helmand, said the radio, NATO troops fired from the air on two houses raised with clay and straw, just like Baba Nazar’s own house. The air strike killed twelve children and two women . . . In the city of Taloqan, at the eastern end of the barchan belt that stretched past Oqa, a Taliban suicide bomber killed an important mujaheddin commander who had supervised all Afghan security forces north of the Hindu Kush. Several other people, Afghan and German, died in the explosion . . . American troops near the city of Jalalabad stormed a compound of a sleeping family and killed a twelve-year-old girl and her uncle, a married man who had two little girls of his own. NATO said the soldiers had raided the wrong house and apologized for the mistake . . . A suicide bomber blew up in a tent at a hospital in Kabul where medical students were eating a poor man’s lunch of rice and tea. There were many dead . . . Four Taliban gunmen stormed and held for ten bloody hours a government building in the city of Khost. There were many dead . . . A roadside bomb ripped through a truck that was carrying two score penniless day laborers to dredge irrigation canals somewhere in Kandahar. There were many dead . . .

Thawra reached for her teacup and took four loud sips and tossed the dregs at the wall. Amber drops and tea leaves trickled down the unfired clay and splashed at the pale wefts and in less than a minute all the liquid was absorbed completely. Only a light yellow stain on the yarn remained, barely noticeable among splotches of chicken shit and dust and bits of straw that had stuck to the thread.

Thk,

thk,

thk,

Thawra’s sickle counted out the hours to the next disaster.

After a while, Boston entered the loom room with her own tea in a porcelain

piala

and sat down on the floor next to the carpet to rest. Her rest lasted as long as it took her to sip her tea once. Then, with a loud sigh and a crack of arthritic bones, she rose and took off her own slippers. Her feet were gorgeous, narrow, finely veined, the color of the sand dunes outside. She squatted on the carpet next to Thawra and picked up a white thread.

It was quiet at the loom. The women worked fast and spoke little, in monosyllabic undertones. Near the northern beam, above the wefts she had strung herself at winter’s end, little Leila was taking a nap in a small hammock her grandmother had woven with coarse saddlebag wool. You could hear her short shallow breaths, dreams escaping through a mouth half open. You could hear Boston’s necklace of keys jingle from time to time, when the old woman leaned forward to peek through the two doorways that separated the women from the men and smile her quick schoolgirl smile, the smile of a heart at peace.

Two young roosters started a fight in the room. They circled each other, and then stood and stared for a long time, necks outstretched, then attacked, flying up, vicious, feathers and down spraying everywhere. Tiny dust puffs exploded from the floor. “Shoo!” Boston hissed at the roosters and they ignored her.

Two young girls walked in, Hazar Gul and a friend. They were wearing eye shadow, uneven strokes of metallic blue and sunset orange. Their mouths were dirty at the corners, their cheeks smeared with grime, their hair cropped short for the summer and stiff with dust. They were extraordinarily pretty. Two runaway starlets. They were chewing gum and their mastication was the loudest sound in the room. “Shoo!” Boston hissed again, and the girls ignored her as well.

• • •

“Look at this,” a Mazar-e-Sharif carpet merchant told me once. His name was Jamshid Bigzada, and he was watching the shop for his older brother, Satar Bigzada, a broad and thunderous Uzbek who had a weak heart, six children, thinning gray hair, and—it said so on his business card—“All Kind Of All Carpet Khwaja Roshani Shereen Taqab Afghani Irani Ibrashimi Moori Available Here.” Bigzada’s shop occupied a section of the first floor of a glass-and-concrete hotel built catercorner from the Blue Mosque during the Communist rule. It faced a perpetual chaotic clot of

zaranj

motor-rickshaws and taxis and horse-drawn carts and motorbikes and bicycles. Legless beggars crawled through this tangle of human and beast and machine, and snotty barefoot boys darted in and out of traffic to thrust mangled cans smoldering with seeds of Syrian rue into the windows of motorists to protect them from curses and earn the boys a few coppers.

To enter the shop, you climbed four or five steps up from the paved stretch of sidewalk where an old man was selling whichever fruit were in season that week and another old man was selling dusty prayer beads and coins from the time of Alexander the Great and the time of the Raj and the time of Zahir Shah and the time of the Soviets. You removed your shoes at the concrete threshold worn to a silver sheen by generations of visitors. Silhouetting in the backlit doorway, you placed your right hand on your heart in a gesture of humility and greeting and stepped inside.

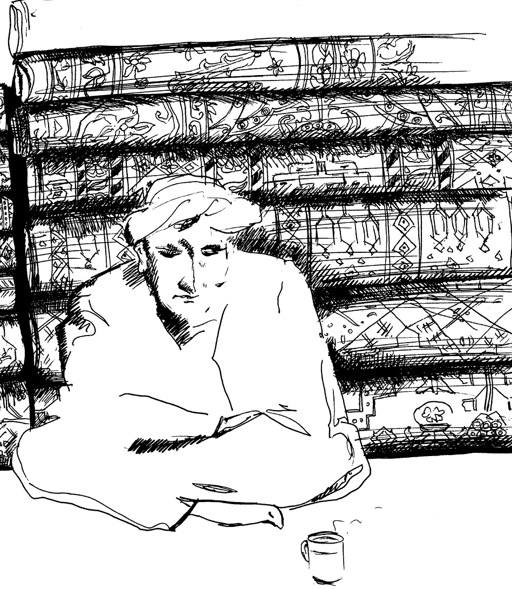

Stepped into a Caravaggio painting. About four hundred carpets lay folded in shoulder-high stacks and hung from walls and draped low divans and lay on the floor one upon the other in a disorder that recalled waterline kelp. The wool suffused the room in burgundy twilight. A kind of regal semidarkness that made you want to bow, that hued everything inside a deeper and more profound shade, like an icon blackened by centuries of supplicants’ candles. Sometimes a white dove, one of the ten thousand said to flock to the mosque, would flutter into the shop and perch on a rug, unearthly pale against the kidney wool, unabsorbable, breaking through all the intense cinnabar and carmine and cerise, and then everyone in the shop would point to it and nod meaningfully and agree that the bird was a good omen. And that in itself was fortunate because—here the merchants and their customers would invoke the witness of God—Afghanistan needed as many good omens as it could get.