The World of Caffeine (13 page)

Read The World of Caffeine Online

Authors: Bonnie K. Bealer Bennett Alan Weinberg

Despite this early flurry of interest in Paris, the predilection for tea abated and, as noted by Pierre Pomet (1658–99), “chief druggist” to Louis XIV and author of

Histoire generale des drogues

(which appeared in English translation as

A Compleat

History of DRUGGS

), was succeeded within fifty years by a taste for coffee and chocolate. It has never revived since. Tea remained available at great expense from apothecaries, as shown in Pomet’s 1694 price list, which offered Chinese tea at seventy francs a pound and Japanese tea at one hundred and fifty to two hundred francs a pound.

Though the British East India Company had been chartered in 1600, none of the British merchantmen brought back samples of tea (or coffee either) in the early years. On June 27, 1615, R.Wickam, the company’s agent in Hirado, Japan, made one of the earliest known mentions of tea by an Englishman, in a letter to a man named Eaton who was the agent in Macao. The reference is part of a list of desiderata that presupposes his correspondent’s familiarity with the leaf: “Mr. Eaton I pray you buy for me a pot of the best sort of chaw in Meaco, 2 Fairebowes and Arrowes, some half a dozen Meaco guilt boxes square for to put into bark and whatsoever they cost you I will be alsoe willinge acoumptable unto for them.”

8

It was not until 1664 that there is any record in the British East India Company’s books respecting a purchase of tea, and that of a shipment of only two pounds and two ounces of “good thea” for a promotional presentation to King Charles II, so that he would not feel “wholly neglected by the Company.”

From this time forward, the Dutch faced a rival in the English, as their competing East India Companies each promoted the sale of its tea and coffee imports throughout Europe. The Dutch took the major step of introducing the coffee plant to Java in 1688, and as a result that island became one of the world’s leading fine coffee producers, giving rise to the epithet “Java” as an enduring nickname for coffee. However, despite Dutch commercial successes, their largely craft-based society failed to grow into a modern industrial economy that could successfully compete in the long run with the one that was to develop in England.

Between 1652 and 1674, there were three largely indecisive wars between the Dutch and English that grew out of their trading rivalry. After 1700, the brief, celebrated Dutch leadership in international trade, science, technology, and the arts increasingly fell into decline, and their fourth and final conflict, fought from 1780 to 1784, ended disastrously for Dutch sea and colonial power. On December 31, 1795, the Dutch East India Company was dissolved, and the triumph of the British East India Company was complete.

Coffee, as well as tea, was both promoted and denounced by Dutch physicians of the time, while the popularity of both drinks continued to increase among all classes. In 1724, the Dutchman Dominie Francois Valentyn wrote of coffee that “its use has become so common in our country that unless the maids and seamstresses have their coffee every morning, the thread will not go through the eye of the needle.” He goes on to blame the English for what he regarded as the deleterious invention of the coffee break, which he calls “elevenses,” after the hour of morning in which it was taken. In the years 1734–85, Dutch imports of tea quadrupled, to finally exceed 3.5 million pounds yearly, and tea became Holland’s most valuable import.

According to one story, the encounter between Pope Clement VIII (1535–1605) and caffeine was a fateful one, in which the future of caffeine and perhaps of the pope’s infallible authority (because, despite many decrees by sultans and kings, none banning a caffeinated beverage had lasted long) in much of Europe may well have hung in the balance.

Trade in coffee in Italy before the turn of the seventeenth century was confined to the avant-garde, such as the students, faculty, and visitors at the University of Padua. Whether as a result of the petitions of fearful wine merchants or in consequence of the appeals of reactionary priests, Pope Clement VIII, in the year 1600, was prevailed upon to pass judgment on the new indulgence, a sample of which was brought to him by a Venetian merchant. Agreeing on this point with their Islamic counterparts, conservative Catholic clerical opponents of coffee argued that its use constituted a breach of religious law. They asserted that the devil, who had forbidden sacramental wine to the infidel, had also, for his further spiritual discomfiture, introduced him to coffee, with all its attendant evils. The black brew, they argued, could have no place in a Christian life, and they begged the pope to ban its use. Whether out of a sense of fairness or impelled by curiosity, the pope decided to try the aromatic potation before rendering his decree. Its flavor and effect were so delightful that he declared that it would be a shameful waste to leave its enjoyment to the heathen. He therefore “baptized” the drink as suitable for Christian use, and in so doing spared Europe the recurring religious quarrels over coffee that persisted within Islam for decades if not centuries.

This bar of heaven having been breached, coffee joined chocolate as an item sold by Italian street peddlers, who also offered other liquid refreshments such as lemonade and liquor. There is an unconfirmed story of an Italian coffeehouse opening in 1645, but the first reliable date is 1683, when a coffeehouse opened in Venice.

In 1669 Mohammed IV, the Turkish sultan, absolute ruler of the Ottoman Empire, sent Suleiman Aga as personal ambassador to the court of Louis XIV. Their meeting did not go well. Arriving in Versailles, Suleiman was presented to the Sun King, who sat decked in a diamond-studded robe costing millions of francs, commissioned for and worn only on this occasion to overawe his foreign guest. But the rube was not razzed. Suleiman, draped in a plain wool outer garment, approached and stood, unbowing, before the king, stolidly extending a missive that he declared had been sent by the sultan himself and addressed to “my brother in the West.” When Louis, unmoving, allowed his minister to take the letter and said that he would consider it at a more convenient time, Suleiman in astonishment begged to know why his royal host would delay attending to the personal word of the absolute ruler of all Islam. Louis, in answer, and true to the spirit of his motto,

“l’état, c’est moi,”

coldly responded that he was a law unto himself and bent only to his own inclination, at which Suleiman, with appropriate courtesies, withdrew and was escorted to a royal carriage that conveyed him to Paris, where he was to remain for almost a year.

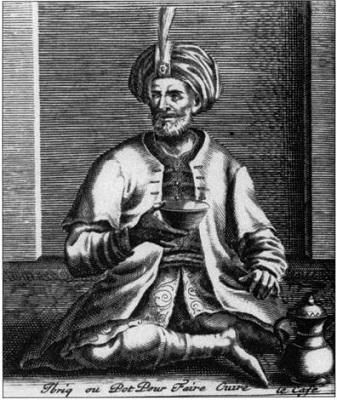

Engraving from Dufour’s 1685 treatise on coffee, tea, and chocolate. This French engraving illustrates a Turk drinking coffee from a handleless cup with an

ibrik,

or Turkish pot for boiling coffee, standing in the corner. (The Library Company of Philadelphia)

Knowledge of coffee and even coffee itself came to France a hundred years before Suleiman. The earliest written reference to coffee to arrive there was in a 1596 letter to Charles de I'Écluse by Onoio Belli (

Lat.

Bellus), an Italian botanist and author.

9

Bellus referred to the “seeds used by the Egyptians to make a liquid they call

cave”

and instructed his correspondent to roast the beans he was sending “over the fire and then crush them in a wooden mortar.”

10

In 1644 the physician Pierre de la Roque, on his return to Marseilles from Constantinople, became the first to bring the beans together with the utensils for their preparation into the country. By serving coffee to his guests, and turning them on to caffeine, he achieved some notoriety among the medical community. Around this time news about coffee reached Paris, but samples of the beans that were sent there went unrecognized and were confused with mulberry. Pierre’s son, Jean La Roque (1661–1745), famous for his

Voyage de

L’Arabie Heureuse

(1716), an account of his visit to the court of the king of Yemen, records that Jean de Thévenot became one of the first Frenchmen to prepare coffee, when he served it privately in 1657. And Louis XIV is said to have first tasted coffee in 1664.

11

Yet, despite all of these precursors, it was Suleiman whose lavish Oriental flair first fired the imaginations of Paris about coffee and the lands of its provenance.

Suleiman, who had made such an austere appearance at court, surprised Paris society by taking a palatial house in the most exclusive district. Exaggerated stories spread that he maintained an artificial climate, perfumed with the rosy scent that presumably filled Eastern capitals, and that the interiors were alive with Persian fountains. Inevitably, the women of the aristocracy, drawn by curiosity and wonder, and perhaps impelled as well by the boredom endemic to their class, filed through

his front gate in answer to his invitations. Ushered into rooms that were dimly lit and without chairs, the walls covered with glazed tiles and the floors with intricate dark-toned rugs, they were bidden to recline on cushions and were presented with damask serviettes and tiny porcelain cups by young Nubian slaves. Here they became among the first in the nation to be served the magical bitter drink that would soon become known throughout France as “café.”

Isaac Disraeli paints a rich picture of taking coffee with the Ottoman ambassador in Paris in 1669:

On bended knee, the black slaves of the Ambassador, arrayed in the most gorgeous costumes, served the choicest Mocha coffee in tiny cups of egg-shell porcelain, but, strong and fragrant, poured out in saucers of gold and silver, placed on embroidered silk doylies fringed with gold bullion, to the grand dames, who fluttered their fans with many grimaces, bending their piquant faces—be-rouged, be-powdered, and be-patched—over the new and steaming beverage.

12

The women had come seeking intelligence; instead, coffee induced them to supply it. Suleiman spoke fluently of his homeland but confined his remarks to such innocuous matters as stories of coffee’s discovery by the Sufi monks and the manner of coffee’s cultivation and preparation, describing for them the plantations of southwestern Arabia, planted around with tamarisk bushes and carob trees to protect them from locusts.

Meanwhile the well-born ladies, the wives and sisters of the leading military and political men in Louis XIV’s realm, felt their tongues loosening with the expansive effects of a heavy dose of caffeine on nearly naive human sensoriums; for the Turkish coffee Suleiman served, “as strong as death,” boiled and reboiled and swilled down together with its grounds, was some of the strongest ever made. Inevitably, they began to talk, to titter, to chatter, to gossip, their words animated by the stimulant power of caffeine. Thus it was that by the same drug, caffeine, which a few decades earlier in the vehicle of chocolate had enabled Cardinal Richelieu to create the conditions for Louis XIV’s absolute power, that any prospect of securing an alliance with Mohammed IV was now undone.

For it was in this way, by plying the women with strong drink, that the devoted Suleiman, though exiled from the Bourbon court, discovered its inner plottings and strategies and concluded that the Sun King dealt with the Turks only to create apprehension in his old enemy, King Leopold I of Austria, and that Louis could not be relied on by the sultan to send troops to assist, for example, in the next siege of Vienna, which, as it turned out, was less than fifteen years away. Perhaps this was the first time in history when the relations between two great monarchs were in large part conditioned, mediated, and even decided by the power of caffeine.

Although coffee was introduced to the French aristocracy and the common man alike in the time of Louis XIV, because of its limited popularity at Versailles, coffee’s further progress into good society was slow. In any case, so long as Parisians could procure coffee only from Marseilles, only the wealthiest could undertake to provision themselves by sending for a supply. The trappings of Turkish customs, including turbans and imitation Oriental robes, endured a brief enthusiasm among the upper classes. But Turkomania became an object of ridicule, and, accordingly, it and the consumption of coffee soon waned. Molière, in his comedy

Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme,

produced when Suleiman Aga was still in Paris, mocked the aristocratic cult that indulged in the sacrament of coffee drinking. Perhaps because of the Gallic aversion to foreign intrusions, the French aristocrats, after indulging a momentary dalliance, turned their backs on coffee, at least for the decade, with disdain. The time for caffeine’s wide enjoyment was not to come in France until Louis XV. In order to flatter his mistress, Madame du Barry, who had herself painted as a Turkish sultana being served coffee, Louis spent lavishly to give the drink vogue. He was to commission at least two solid gold coffeepots and direct Lenormand, his gardener at Versailles, to plant about ten hothouse coffee trees, from which six pounds of beans would be harvested annually, for preparation and service to his special friends by the king’s own hands.

13